Blockchain 101: Blockchain Safari

This is part of a larger series of articles about Blockchain. If this is the first article you come across, I strongly recommend starting from the beginning of the series.

Our journey has already taken us through the inner workings of some of the biggest Blockchains out there — Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Solana.

It’s a lot to take in, yes... But the web3 landscape is a vast one, and we have much, much more to cover yet.

I trust that with all the information we’ve churned through by now, we’ll be more or less familiar with the general ideas in Blockchain, and we’ll be able to process new concepts and ideas easily.

So today, I want to do something slightly out of the ordinary, and not focus on a single Blockchain, but on multiple ones, and explore the core ideas they pursued in their design. A short sightseeing tour of the Blockchain space, if you will.

To keep this brief, I’ll go over the most important ideas of the Blockchains we’ll talk about today. This means that we’ll not really go into the finer details, so I encourage you to continue your research on your own if any of them catches you interest.

Remember, the goal of this series is not to dive full deep into any of these Blockchains, but to learn the core concepts behind them, and the innovations that have transformed — and are still transforming — the industry.

Ready? Action!

Extending UTXO

Back in the very first chapters of this series, we studied Bitcoin, and how it proposed an initial approach to modeling money: the Unspent Transaction Outputs Model, or simply UTXO.

Immediately after that, we talked about Ethereum and Solana, and this UTXO model was relegated to the background while accounts took the main stage. Why is that?

The answer is very simple, really: programmability.

Account-based models condense the state of the Blockchain into individual accounts — be it user accounts, contract or program accounts, etc. The state of the entire network is neatly packed into these smaller storage boxes, one per account.

We could even think of these pieces of states as being a big, unique structure representing each account, holding its state. I don’t wanna say “object” because that may be confusing for the next article... But yeah, kinda like objects.

This architecture makes it really easy to access and modify state, because we know where the data is: in each account! We say that accounts are stateful — they hold a mutable state.

Contrast this to Bitcoin’s UTXO model, which is scattered all over the place. What’s more, each UTXOs doesn’t really hold any mutable state — just an immutable value. In this sense, Bitcoin is said to be stateless.

Trying to implement logic over this sparse, rigid state of the Blockchain does seem like a complicated endeavor indeed — and exactly the reason why other platforms like Ethereum chose accounts for programmability.

When we put it like this, it sounds like UTXO is the “inferior” model — but in reality, it has some interesting inherent qualities in areas where the account model struggles. In particular, it naturally allows better parallelization, and clearer (and simpler) transaction validation.

So here’s a question: could we somehow support logic in UTXO systems, without losing these benefits?

A Note on Bitcoin

Before we move onto the protagonist for this section, we’ll need to circle back into how UTXOs really work in Bitcoin. This will help us better understand what comes afterwards.

In order to be able to spend a UTXO, we need to meet certain conditions. These conditions are established in the form of locking scripts, which define the conditions under which each particular UTXO can be consumed (spent).

These scripts are written in Script, a “mini” programming language (it’s not Turing-complete).

While this means that Bitcoin supports logic to some minor extent, UTXOs normally use a small set of standard locks, which involve some form of simple digital signature from the spender for unlocking (and consuming) the UTXO.

Really, when we ask ourselves if we can add logic to this model, we’re asking for a little more than these locks — we want to fully support logical operations! So how do we do that?

Cardano

While there have been many attempts to add programmability on top UTXO-based networks (such as Rootstack), I think one of the most elegant and ingenious approaches to extending the core model is the one proposed by Cardano, in the form of what they call the Extended UTXO model (EUTXO).

We won’t really focus on Cardano’s consensus algorithm today, because there aren’t many surprises there: Cardano was one of the first Proof of Stake networks out there, with its Ouroboros protocol.

It’s worth taking a look though, if it piques your interest!

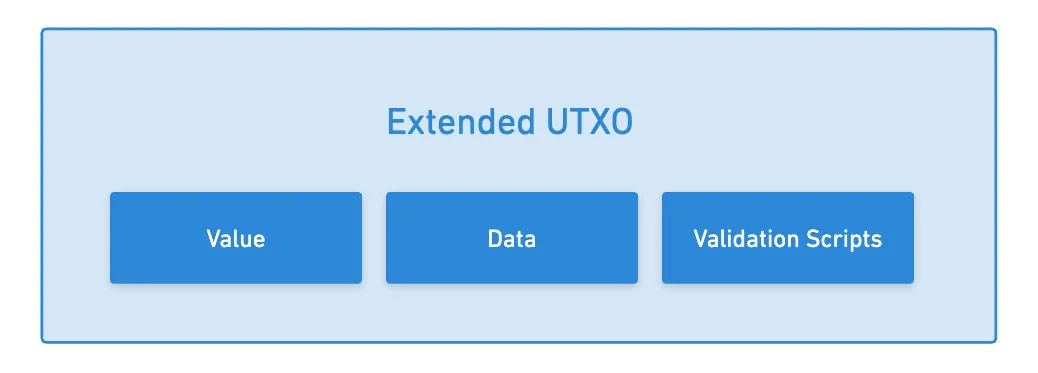

So how does this extension work? Well, instead of locks, Cardano adds some complexity into the mix by allowing each UTXO to carry some new exotic elements alongside its value: arbitrary data and validation scripts.

By adding these validation scripts, we can impose more complex conditions to the unlocking process. We can place signature restrictions like we did in Bitcoin, but we’re now able to require other logical conditions, such as timelocks.

These validation scripts are written in a language called Plutus.

Said differently: the validation scripts define the conditions under which the UTXO can be spent. All of the logic and data needed to validate a transaction is provided as part of the transaction itself — no external state checks are required.

What’s interesting about this design is that all the benefits of using UTXO are retained, because every transaction is self-contained. The network can easily parallelize validation, which is in itself much simpler than in account-based Blockchains.

But of course, this comes with limitations. It’s particularly hard to set up interactions between separate pieces of state (UTXOs), as there’s no easily accessible global state, neatly and mutably stored.

Cardano's approach again showcases a core theme in Blockchain design: there's no perfect solution, only different trade-offs.

It’s worth noting that when you spend money in Cardano, you’re not just moving value — you’re also programming the conditions for how that money can be spent next. Every transaction creator becomes a “programmer” of the new UTXOs they create, deciding what scripts and conditions will govern those outputs.

So yeah, while EUTXO gives you the benefits of statelessness and parallelizability, it makes complex state interactions more difficult than account-based systems. Different problems, different solutions — and that’s exactly what makes this space so interesting.

Alright, one down! What’s next?

Consensus and Trust

As decentralized systems, all the Blockchains rely on some form of decentralized consensus to secure their networks.

We’ve only covered Proof of Work (PoW) and Proof of Stake (PoW) — but they are pretty much everywhere!

These consensus algorithms are marvelous displays of engineering, but they do come with some complications attached. For instance, PoW is very energy-inefficient, and PoS is a quite complicated multi-step dance of precise decentralized coordination.

We already know there’s a reason why this exists though: to keep things trustless. Since anyone can join the network as a miner or validator (as long as they meet the required conditions), we can’t trust nodes to be honest, and so we need to put measures in place so that the entire system works flawlessly.

But what if we didn’t need all that? What if consensus could happen much faster, and without all these complications?

Ripple

This is what Ripple tried to achieve with its network, the XRP Ledger.

And to avoid any confusions from the get go, I want to clarify that the XRP Ledger is often referred to as Ripple as well.

Ripple takes a radically different approach to consensus. Instead of opening participation to everyone, it has a set of trusted participants that collectively agree on the state of the network.

These participants are called validators — but they are fundamentally different from the validators in PoS.

And while we’re at it, technically speaking, the XRP ledger isn’t a Blockchain, in the sense that it doesn’t use the same underlying data structure. Instead, it’s a Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), where validators agree directly on the next state of the ledger without any mining or block production.

We tend to call these types of systems “Blockchains” anyway. It’s about functionality rather than actual implementation.

The key distinction here is that consensus happens through agreement among trusted nodes, rather than through competition or random selection. And since validators don’t need to perform heavy computations or stake tokens to propose blocks, the network can process transactions very quickly — often settling payments in just a few seconds.

But then... What about our usual motto don’t trust, verify?

Well, of course, this comes with an important trade-off: speed and efficiency, at the cost of a semi-permissioned trust model.

Validators are typically known entities, which can help put our minds at ease — but trust is ultimately required.

Yeah, this isn’t as decentralized as other Blockchains might be. But you know what? It’s extremely effective for Ripple’s primary use case: fast, low-cost payments and cross-border transfers.

If anything, this goes to show that decentralization is not a static concept, but more of a spectrum. Different applications may require different balances between openness, trust, and efficiency.

And again, this is the trilemma in action!

More Consensus Alternatives

By now, our roster of known consensus mechanism is composed of just 3 general strategies: Proof of Work, Proof of Stake, and the Ripple protocol.

To me, this number still feels small. As in, I would imagine that there are other strategies out there.

Even worse, if we treat Ripple as an outlier, then we only have two alternatives to choose from!

It just can’t be all there’s to consensus, right?

Other strategies indeed exist, but to be fair, consensus is not an easy problem to solve. It’s very important that any mechanism we devise is very resilient to bad conditions, which usually means how tolerant the network is to both unintentional and intentional faults.

What’s more, there are different flavors to PoW and PoS. Their name might be the same, but that’s an oversimplification of the underlying mechanism.

With this in mind, let’s examine another consensus algorithm, and how it fares against the ones we already know.

Avalanche

The Avalanche network uses a completely different solution, where we don’t have nodes competing against each other, nor we have them take turns — instead, it relies on constant communication, and sampling.

Their mechanism is called the Snowman Protocol.

The documentation on their site is fantastic and very didactic, so I recommend taking a look.

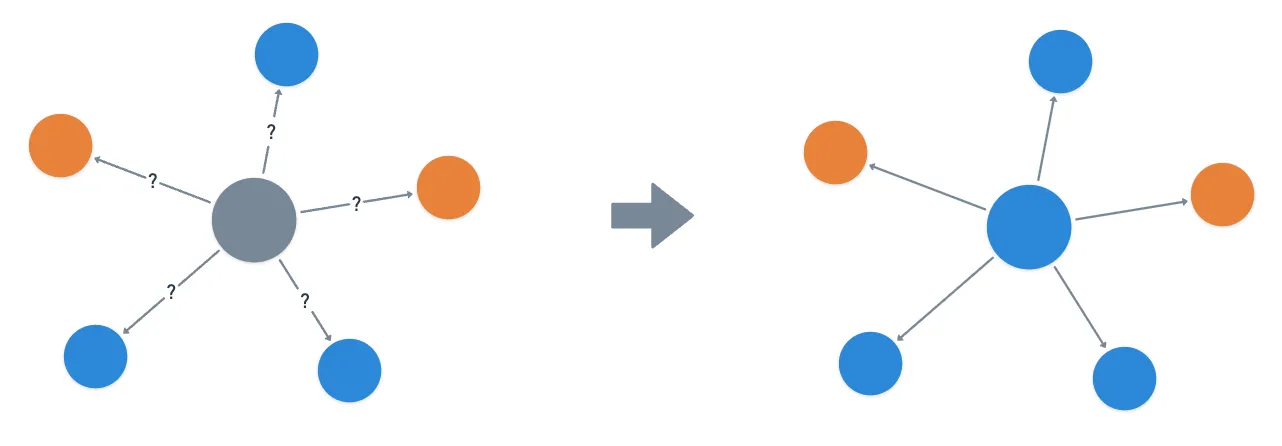

It’s based on a beautifully simple idea: when a validator needs to make a decision, like the order of two conflicting transactions (as in, a double spending attempt), it randomly samples a small group of other validators and asks “what do you think about this?”.

Based on the responses, the validator might change its own preference. And then, it asks another random set of validators. And then another. And this process is repeated until the validator becomes confident enough in a particular choice to finalize it.

What makes this approach so interesting is that it’s leaderless — there’s no single validator in charge of proposing blocks or making decisions. Every validator is doing the same sampling job simultaneously, and under the right conditions, they all end up agreeing.

It’s a metastable solution — the system naturally moves towards consensus states, similar to how a ball will move to the bottom of a hill. Or in physical terms, it’s as if it moved towards a state of lower potential.

But that’s precisely the point: what are those right conditions?

To answer this, we need to analyze what happens when nodes go rouge, and stop follow the established rules. We call these malicious nodes.

Traditional consensus mechanisms like Proof of Work can tolerate up to (or really, ) malicious nodes. Others, like Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (which we haven’t covered in the series), can stand up to malicious nodes. Avalanche, however, can only handle a smaller fraction — in theory, a maximum of malicious participants, where is the total number of nodes.

In principle, that sounds worse. Naturally, we can ask what is there to gain from this sacrifice — and the answer is speed. Transactions are finalized really fast in Avalanche: it takes no longer than 1–2 seconds for a transaction to be finalized.

That’s like, really freaking fast.

So, how do we make nodes behave correctly? Well, we can’t force them to, but we can put some economic incentives in place, in the form of staking.

And I know what you might be thinking — but Frank, isn’t this a Proof of Stake solution then? Well, in a sense, yes.

What I want to highlight here is that the overall mechanism is very different from, say, Ethereum’s. Exactly the point I was making earlier: just because two use a Proof of Stake solution, it doesn’t mean they work the same.

Alright, so that’s Avalanche’s consensus in a nutshell! It’s an elegant probabilistic solution, which achieves high speeds at the cost of some security guarantees.

Avalanche has some other tricks up its sleeve, like its multi-chain architecture. We’ll come back to these ideas later in the series, but not focusing on Avalanche — so I encourage you to read more about this Blockchain on your own!

Privacy

Another common factor in all the Blockchains we’ve seen so far is the fact that they are public.

By this, I mean that everyone can see every transaction, every balance, every wallet — everything is public. After all, that’s part of the appeal: the system is verifiable by anyone, anytime.

Let’s pause for a second there, and ponder the implications. Is this always a good thing?

Since everything is public and transparent, anyone could see your balance. Someone who holds a lot of money might qualify as a prime target for attacks. Then, we could argue that in this kind of scenario, some degree of privacy could be a good thing.

Time for another question then: how do we achieve privacy on a public Blockchain?

Monero

While there are multiple solutions to this problem (as we’ll see later in the series), one of the earliest ones was proposed by Monero.

This Blockchain is one of the few remaining PoW networks out there. The core innovations are not on the consensus algorithm though — but instead, on how the design and architecture are built around the idea of privacy by default.

Monero hides three key pieces of information: the transaction sender, the receiver, and the sent amount.

Pretty much everything!

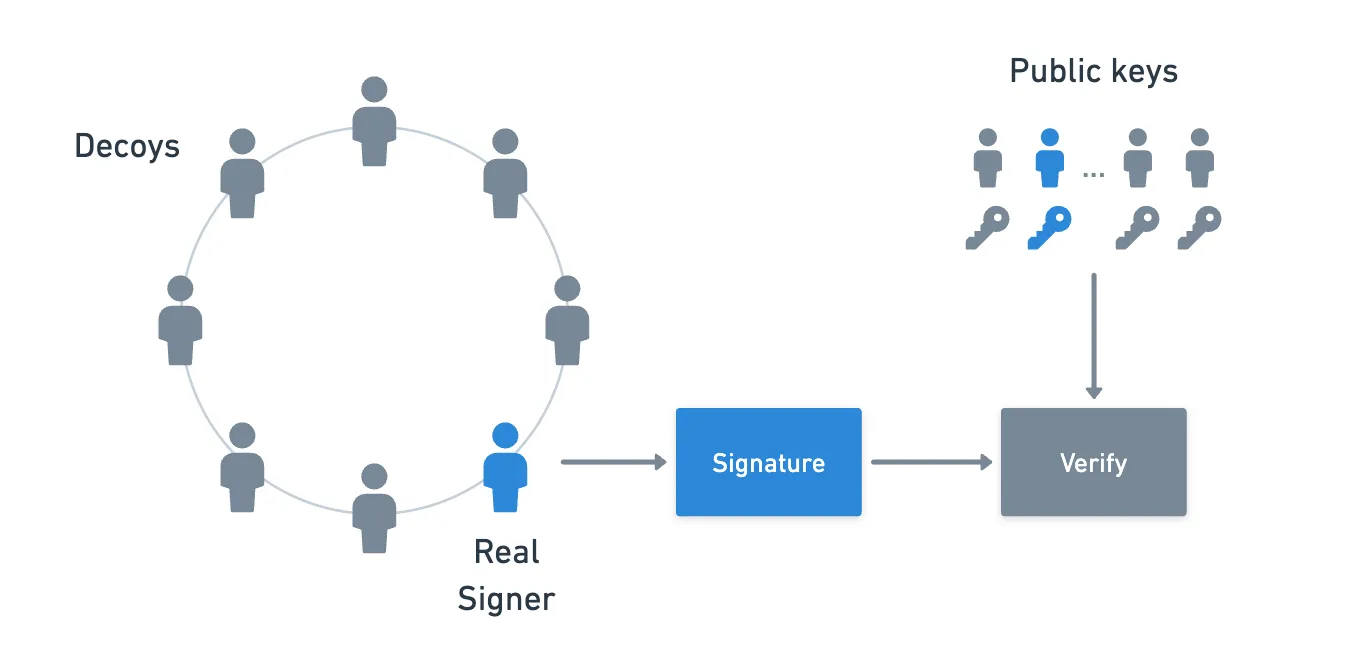

Let’s briefly look at how each of these elements are hidden. First, let’s talk about the sender. In normal circumstances, a sender would simply need to produce a standard signature (ECDSA) — but that doesn’t hide their identity. So instead, a ring signature is used. Essentially, you grab a bunch of public keys that serve as decoys, and use a construction that produces a signature in such a way that it’s not possible to distinguish the real signer from the decoys.

If you’re interested, you can find more about the specifics of this algorithm here!

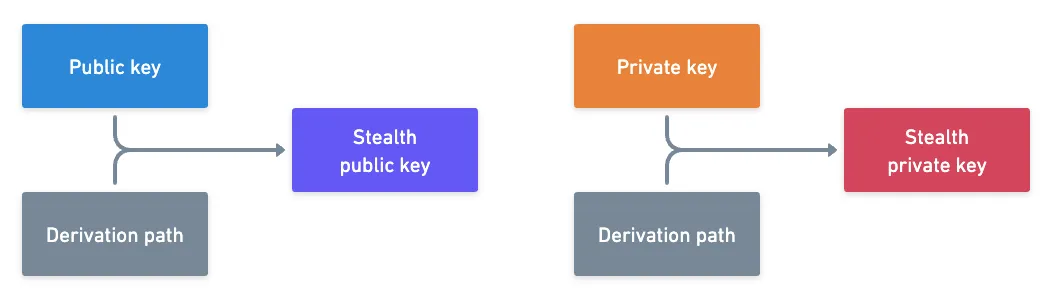

Next, we need to hide the receiver. What we want is to prevent someone from watching our address, and knowing about our activity. And the solution is exceptionally simple: stealth addresses. A stealth address is an address derived from your original key pairs. Through a derivation path, you obtain an address that looks completely unrelated to your real address, but is cryptographically linked to it. And the clever part is that you can easily obtain the associated private key, using the same derivation path, and your original private key — so you effectively own this derived stealth address!

And finally, RingCT (Ring Confidential Transactions) hides the transacted amount. This is achieved via a technique called Pedersen commitments to prove that a transaction is valid. It’s like putting both the inputs and outputs of a transaction into separate envelopes, and mathematically proving they contain the same amount of money — without ever opening the envelope!

It’s a quite simple and elegant technique, and I encourage you to read about it here!

All in all, Monero combines these cryptographic primitives wonderfully, and creates an end-to-end privacy framework: no one can see who sent funds, who received them, or how much was transferred.

Apart from not allowing logic (it doesn’t support Smart Contracts), we must ask ourselves what the consequences of this level of privacy are. For example, auditing is harder, which could raise regulatory concerns. The promise of privacy can attract unwanted users seeking a platform where they can keep their questionable activities hidden!

Nevertheless, from a purely technical perspective, Monero represents one truly advanced real-world implementation of applied cryptography in Blockchain.

Privacy is a hard problem — and Monero shows what’s possible when you put it at the center of your design.

Sidechains

To wrap things up for today, let’s talk about sidechains.

A few articles back, we talked about rollups, or layer 2 (L2) Blockchains. The proposed idea was simple: we perform calculations off-chain, but then commit information to the base Blockchain — the layer 1 (L1) — as the ultimate source of truth.

Often times, this is phrased as “the L2 inherits L1’s security”. I don’t like this way of putting it — it’s over-simplistic, and at least for me, it fails to capture the true essence of the matter.

What really happens is that the L2 depends on the L1 to move forward — they don’t have their own consensus mechanism.

If you have time and want to do the research, try Googling things like “Arbitrum consensus mechanism” or “Optimism consensus mechanism”. You’ll quickly find that these systems don’t have a full consensus mechanism of their own, but a specification of how and when to commit information to Ethereum!

By “security”, what we really mean is that these L2s depend on the security provided by the consensus mechanism of the L1.

With this new information, it’s much easier to define what a sidechain is: it’s just a fully independent Blockchain, with its own consensus mechanism, that chooses to publish it’s current state to another Blockchain as sort of a checkpoint.

So, what are some examples of sidechains? I just so happened to have a conversation about this with a few coworkers at the time of writing this, and we came across something interesting: turns out one of the most cited examples of L2s is in fact a sidechain — and it’s a very well-known Blockchain!

Polygon

Yeah, you read that right!

The Polygon network that most people use — Polygon PoS — is indeed a sidechain, not a layer 2.

Polygon PoS has its own set of validators — around 100 of them — running their own consensus mechanism. These validators process transactions, create blocks, and secure the network completely independently from Ethereum. And every so often, Polygon simply posts these snapshots to Ethereum.

This has a couple consequences:

- On one hand, if Ethereum goes offline tomorrow, Polygon would keep running just fine.

- But on the other hand, if Polygon’s validators decided to collude (aka work together) and steal everyone’s funds... Well, they could, because Polygon’s security depends on its own validator set, not Ethereum’s.

So again (and unsurprisingly by now), it’s a a matter of trade-offs.

We sacrifice a bit of decentralization by trusting a smaller and independent set of validators, but in exchange for cheaper and faster transactions.

One question that may pop in your head at this point is “okay, but why post a snapshot to Ethereum, if Polygon is fully independent?”. Well, there are several reasons why this is might be important. Namely:

- Dispute resolution: if there’s ever a major dispute about Polygon’s state, then the Ethereum checkpoints could serve as a last resort to resolve them. In such a scenario, we do rely on Ethereum’s security!

- Bridge security: To move assets between Ethereum and Polygon, you need bridges, because they have disconnected states. By providing these snapshots, we give Ethereum verified information about Polygon’s state, making bridges far more secure.

- Exit guarantees: In theory, if Polygon’s validators went rouge, users could prove their balances in Polygon through these checkpoints, and potentially exit back (recover their tokens) to Ethereum. It would be complex, but in theory, it could be done.

In short, it’s a matter of credibility.

Polygon’s approach has been incredibly successful. Regardless, Polygon (the company) is working on other solutions alongside their original sidechain. In particular, Polygon zkEVM is their latest development — and this one is a true L2 solution we’ve already covered!

Terminology mixups aside, it’s important to understand the design differences of these types of systems, and the implications they may have!

Summary

And that’s a wrap for now!

We’ve covered a lot of ground today. Part of the idea was to show just how much diversity there is in the Blockchain world. I believe it’s crucial to get acquainted with the core ideas and concepts out there to better navigate this field!

I just hope it was not terribly confusing!

What is clear is that there’s no single one-size-fits-all solution in Blockchain design — or at least not yet. Every choice involves trade-offs, and different applications call for different approaches. EUTXO trades complex state interactions for parallelization. Ripple trades decentralization for speed. Avalanche trades security for speed. Polygon trades some security for performance. And Monero’s case is a little different, for there’s a more subtle moral debate around it.

Understanding these trade-offs is key to navigating the web3 landscape.

And at least for me, getting to understand them is one of reason why I find this topic so fascinating!

Even after this compendium of new ideas, we still have a lot to cover.

Next time, we’ll take a look at parallelization in Blockchain, and cover two modern solutions: Aptos and Sui.

Until then!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.