Blockchain 101: Consensus Revisited

This is part of a larger series of articles about Blockchain. If this is the first article you come across, I strongly recommend starting from the beginning of the series.

Throughout the previous two installments, we’ve been focusing heavily on the machinery that allows Ethereum (and EVM-compatible chains) to execute programs created by us, the users. Not any kind of programs — Smart Contracts, to be precise. Pieces of logic that are the only way to change an otherwise immutable custom state that lives on the Blockchain.

But as we already know at this point, that’s only part of the story.

You can spin up a local Blockchain (node) with tools like Hardhat or Foundry (using Anvil). These will understand how to execute transactions and Smart Contracts, but they won’t be a true Blockchain — in the sense that such a node is disconnected from the rest of the world.

What we need to build a true Blockchain is to achieve consensus with other network participants. Agree on the so-called state of the world with other nodes. And abide by the rules that doing so imply.

Thus, it’s finally time to talk about consensus in Ethereum.

Ethereum and Consensus

In the early days of the network, the consensus mechanism of choice for Ethereum was Proof of Work (PoW) — the same mechanism (at least in principle) used by Bitcoin still to this date.

We’ve already discussed some of the problems this mechanism has: low throughput (i.e. low transaction processing speed of the network), high energy consumption, and also the fact that mining was concentrated in large mining farms, instead of being a truly decentralized system where guys like Bob, running a node in his computer, could participate in.

Although, I must say, true decentralization is really hard to achieve. We’ll discuss this throughout our journey together, don’t worry.

The Ethereum Foundation identified those flaws, and sought to steer the ship in a different direction.

From its conception, Ethereum was ground-breaking in that they gave the world dynamic state management in the Blockchain. But to be fair to other Blockchains, by the time the new consensus mechanism was proposed, the web3 (a.k.a. Blockchain-based) ecosystem had already bloomed, and a plethora of different Blockchains with different value proposals — along with new consensus mechanisms had emerged.

What I mean is that the new consensus algorithm, Proof of Stake (PoS), was not as new and disruptive as the introduction of Smart Contracts. The way in which Ethereum did the switch however, was pretty interesting, and we’ll talk about that on the next article. Let’s now explore how PoS works.

But first, a short refresher on PoW is due.

Proof of Work

As you may recall from a few articles back, Proof of Work is a consensus mechanism that relies on a difficult puzzle to provide fairness. By this, we mean a few things:

- nobody knows in advance who the next block creator will be, which is important to avoid targeted malicious activity.

- a malicious node cannot produce blocks faster than the rest of the network.

- nodes are incentivized to search for new blocks (mine) because they get a reward from doing so.

But that same puzzle that provides all these good things, is also the mechanisms’ biggest design flaw: it’s tremendously inefficient. A lot of time and computing resources are spent on solving the puzzle — a partial hash pre-image problem — and not on growing the Blockchain per se.

Naturally, we may wonder: does it have to be like this? To which the answer is a resounding no. Although, it’s not as simple as adjusting a few knobs here and there: we have to rethink how we approach consensus completely.

We need two main ingredients for any good consensus mechanism:

- A way to guarantee the contents of blocks are valid (meaning that transactions are valid and correctly signed).

- A way to ensure that no single actor controls the network.

We’ll talk about the second point in a moment, but let’s first focus on the former. How do we do that?

Block Validation

In Bitcoin, nodes produce valid blocks at random times, because the puzzle is randomly solved by some node in the network. What makes the block “valid” is the presence of a certain nonce value, that produces a very specific hash output when we pass all the contents of a block through a hash function.

However, the transactions themselves are not necessarily valid. Because of this, every single node checks every single block they receive. If any transaction is invalid, then the entire block is rejected. We can say that a block in these conditions is effectively rejected by the network.

In other words, we trust no one. Which is in line with the usual motto:

![]()

![]() Don’t trust, verify.

Don’t trust, verify.![]()

![]()

All this stems from the fact that block producers are not controlled in any way. They just need to put in the work. Finding a valid nonce is enough for a block to be valid, but we still need to inspect the transactions.

So, how about instead of living in such a Wild West world, we try to put some order, and assign roles?

Validators

In Proof of Stake, miners are replaced by validators. The key idea here is that validators have a specific role: to propose and validate blocks. These validators don’t need to solve any cryptographic puzzles at all — so that inefficiency is out of the picture. Simple, right?

Not quite! We need to define a few things for this to work. For instance:

- Who or how can a node be a validator?

- How is a validator selected to propose a block?

- How do we ensure that the block contents are valid?

It’s totally fine to ask these kinds of questions — solid answers are what constitute a reliable consensus mechanism!

Let’s start from the very last one. Something that we could do is to perform some cross examination of blocks. Of course, validators are in charge of this validation process.

Duh!

But we need to ask ourselves: what would be an invalid block?

Fundamentally, it’s just a block that contains transactions that don’t follow the rules of the network. A transaction could be invalid due to various reasons, such as:

- Double-spending attempts (using the same funds twice).

- Invalid signatures (someone trying to spend funds they don’t control).

- Smart contract execution that violates the EVM rules.

- Transactions with insufficient gas.

The key difference lies in how these invalid blocks are handled. Invalid blocks can be proposed, but there’s an incentive not to do so: validators (the proposers) have skin in the game.

What does this mean? That if you propose an invalid block and your attempt is caught by other validators, you’ll be penalized.

How, you ask? Well, this brings us to one of the questions we posed earlier: just who can be a validator?

The answer is in the name of the protocol itself: stake.

Stake

To become a validator in Ethereum, a node must deposit exactly into the staking contract. This serves two purposes: it gives you the privilege to propose blocks, but is also a security deposit or bond.

I must admit, the value seems quite random at first sight. But in fact, it’s a carefully chosen value, that mainly aims at keeping the number of validators at a healthy amount.

If validators misbehave, either by proposing invalid blocks or by going offline when they should be validating — a portion of their stake can and will be slashed (taken away).

What we have then is an economic punishment mechanism. Of course, validators have positive incentives to participate in consensus as well — just like in Bitcoin, they get rewards for their efforts.

Okay, so let’s say you’ve staked , and you’re now running a validator node. Congrats! What happens next?

Proof of Stake In Action

We no longer have to hold a computational race to determine who proposes a block — we now have a set of validators who are willing to put their stake on the line to propose valid blocks.

All we need to do, is decide how we orchestrate validation — how we choose who does what, and when.

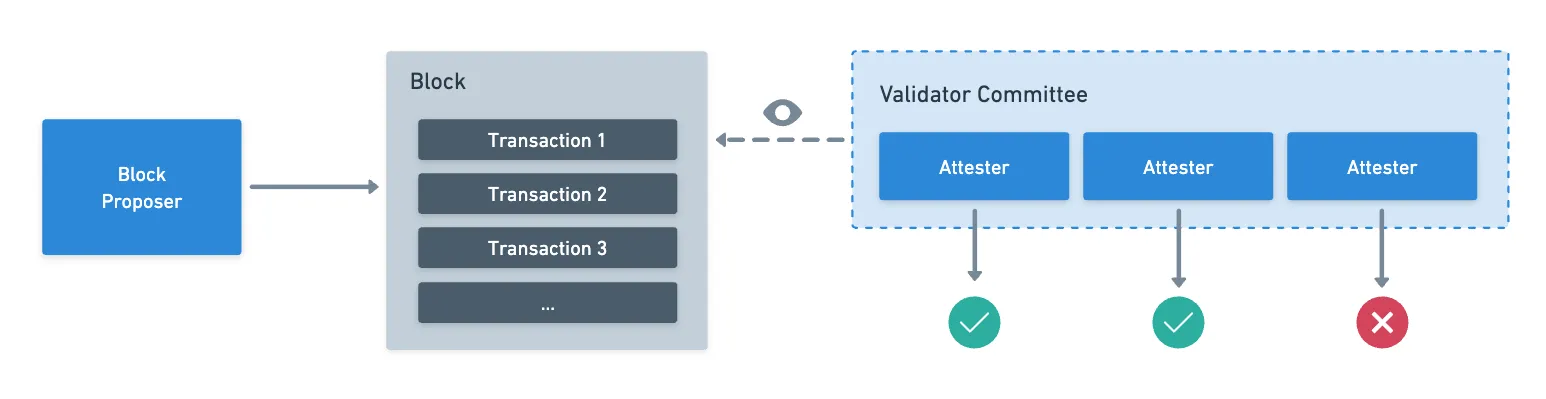

Ethereum’s PoS protocol uses a pseudo-random selection process (using Verifiable Random Functions) where each active validator has an equal chance of being chosen as the next block proposer. But remember — we also need other nodes to validate the new block. So besides the proposer, a committee of validators is also selected.

Typically, attesters are selected. The proposer and validator committee (or attesters) is rotated every seconds, which results in the time Ethereum takes to produce a Block.

Furthermore, validators are notified a short time in advance when they’ll need to propose and validate blocks. This allows them to prepare properly, not wasting resources while they are idle.

The beauty of this system is its efficiency. No computational resources are wasted on solving puzzles. The network is based on the economic deterrent that is the slashing mechanism — malicious activity of nodes results in their stake going:

Now, the happy path is pretty easy to understand. Validators in the committee will attest that the proposed block is valid, and when at least of the committee has attested to the validity of the block, then the block is “accepted”.

It’s worth noting that attestations have some structure — they aren’t just votes for the new block. They also have some more information, like what each attester sees as the head of the chain — the last block. And they are also signed!

We’ll talk about what “accepting” means in a moment. But first: exactly what happens when some validator detects something fishy?

Handling Maliciousness

We need to distinguish between different types of malicious behavior:

- Invalid blocks: blocks with invalid transactions. Honest attesters simply won’t sign attestations for them.

- Equivocation (Double Proposals): this happens when a proposer essentially proposes (at least two) different blocks, and broadcasts them to the network during attestation.

- Inactivity: when validators or attesters are go offline during their turns to propose and validate blocks, effectively hurting the network because block production might be stopped during their turns.

The last one might not sounds like “malicious activity”. But remember: in a decentralized world, we can trust no-one. Thus, we cannot distinguish between an honest disconnection, or deliberate inactivity — so both are considered malicious behavior.

Each of these scenarios is handled differently.

In the case of blocks being invalid, if attesters are honest, the block simply won’t be attested by them, and the required of acceptance won’t be reached. The block dies off on the shore, and the validator essentially wastes their turn to reap rewards. Tough luck.

Inactivity is where penalties begin. Because essentially, the network won’t produce blocks if enough validators are inactive. Those validators start losing a portion of their stake through small penalties, which increase over time.

Equivocation is taken to be more serious. It’s like a deliberate attempt to cause chaos in the system. And there’s cryptographic evidence for this, because all actions a validator takes are signed — so this is what we call provably malicious activity. In this scenario, slashing happens, the validator that was caught sees a portion of their stake burned.

What’s clever about this design is that the punishment fits the crime. Honest mistakes or temporary connectivity issues result in minor penalties, while deliberate malicious actions are more severely punished.

It’s also worth noting that slashing doesn’t happen immediately. A period of time exists (let’s call it the withdrawability period), where the slashed validator cannot withdraw their remaining funds. During this time, the protocol can apply any additional penalties if new evidence is found on things such as coordinated attacks.

Right now, that time is around hours.

So, that’s Proof of Stake in a nutshell. Of course, this is just the high level, and implementation details are not exhaustively covered — but this should be more than enough to provide a good idea of how the system works.

This mechanism also enables something that was not possible in Proof of Work: block finality. Let’s talk about that next.

Finality

Not to be confused with fatality.

So far, we’ve talked about blocks being “accepted”.

In Bitcoin, we saw how the network could present temporary forks. This had one unpleasant consequence: we cannot know if the latest block on the Blockchain will end up being a part of it, or if it will eventually be discarded. So we had to wait for block confirmations — blocks on top of the one we’re interested in.

Clearly, it’s important for us users to have the ability to determine if a block is included in the Blockchain. In fact, this idea has its own name: a block or transaction is finalized (or final, or has finality) when we can be sure it will recorded permanently on the Blockchain

Bitcoin has probabilistic finality. This means that we’re never 100% sure that a block is in the Blockchain, but the probability of this not happening goes down drastically with each block confirmation. The deeper the block is on the Blockchain, the lower the probability.

At the very least, this is not convenient.

With Proof of Stake however, something really interesting happens — at some point every block will have absolute or deterministic finality. But how does this happen?

Finality in Ethereum

We’ve already talked about how time is organized in Ethereum. Slots are the 12-second periods where new blocks are proposed and voted for.

There’s also epochs. Epochs are groups of slots (about 6 and half minutes). And at the end of each epoch, validators vote on pairs of checkpoints — the first and last block in the epoch.

They need to vote because this is a distributed system, so they might have different views of the current state of the network.

In similar fashion to how blocks are validated, when a checkpoint receives votes from of the validators, the checkpoint becomes justified. When that happens, any previous justified checkpoints (deeper in the Blockchain) become finalized.

In practice, this means that after about epochs (which are roughly 12–15 minutes), your transaction reaches absolute finality. And at that point, you can be absolutely sure that your transaction will be included in the Blockchain!

Well, almost absolutely sure. Truth is that if the network is willing to lose huge amounts of ETH through slashing, then validators could in theory rewrite part of the history of the network (the Blockchain itself). But there are billions of dollars worth of staked ETH — so the security is based off the fact that no-one’s willing to lose that much.

Which is a pretty strong assumption.

This absolute finality mechanism is called Casper FFG (Friendly Finality Gadget). It’s one of the major upgrades that were implemented alongside the transition to PoS.

Pretty cool, huh?

Summary

The new and improved Ethereum consensus mechanism mitigates many of the problems with the old Proof of Work system. It introduces a different set of problems though, which are tackled via strong economic models, and a clever distributed system architecture.

Of course, there’s a lot more complexity under the hood. But again, this series is not aimed at providing all the super-deep-level insights, but neither at going super high-level. I reckon today’s article sit comfortably somewhere in-between.

Proof of Stake comes in different flavors — Ethereum’s approach is not the only possible approach. Other Blockchains have introduced tweaks and changes in the hopes of achieving lower block times, higher throughput, faster finality, or stronger security guarantees. Which is ultimately a good thing, I believe — as better mechanisms are discovered, the overall experience for us users should improve.

We’ll talk about PoS variations and other consensus mechanisms soon enough.

We’ve covered quite a few things about Ethereum by now. Next time, we’ll close the chapter on this Blockchain, so we can move on to discover new horizons.

See you then!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.