Blockchain 101: Transactions

This is part of a larger series of articles about Blockchain. If this is the first article you come across, I strongly recommend starting from the beginning of the series.

In the previous installment, we presented what a Blockchain is, and also talked through a few of the concepts around this technology. Essentially, we focused on the structural aspects of the model — its literally nothing more than a chain of blocks.

This is a great start to our journey, but it's not even nearly close to being the full story. There still a lot for us to cover!

And to start us off, I want us to focus on the transactions, as they are at the very core of any Blockchain. Bitcoin was conceived as a cash system that could improve upon some of the problems of centralized processors — so it's only natural that the ability to transact is one of the most (if not the most) important aspects of this technology.

Off we go!

Building a Transaction

Transactions in Bitcoin are quite simple to understand. Again, it's a cash system — so transactions only move money from A to B.

When we move to other Blockchains, we can see that transactions can do much more than that!

In fact, it's so simple that we can try and create such a model from scratch.

To get us started, let's imagine each transaction moves a single coin.

In this simplified scenario, a sender (Alice) only needs to specify a receiver (Bob), and the amount of money being transferred would just be 1. Easy, right?

Well, there's a problem: the system needs to understand who Alice and Bob are.

In terms of our everyday applications, we may think "hey, that sounds awfully similar to a username!". You'd be forgiven to think a Blockchain could handle such a common thing — but our basic model doesn't support it.

Not out of the box, at least.

So how does Alice tell the Blockchain that she wants to send a coin specifically to Bob? Just who is Bob? And since we're at it, what makes Alice be Alice? What defines their identities on the system?

Private and Public Keys

We've already discussed how a sender needs to give consent for a transaction to happen — Bob cannot force Alice to send her any money.

I mean… I wouldn't use a system that allows robbery by design!

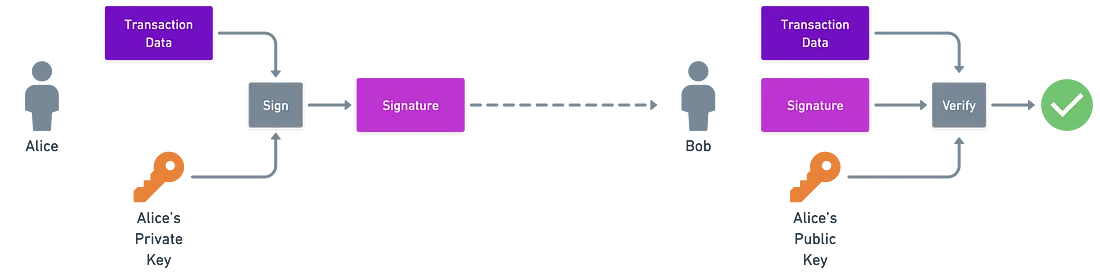

The way this consent is achieved is by attaching a digital signature to a transaction. We don't need to fully understand how digital signatures work — only a couple of their key elements. This will help explain what we understand by "Alice's identity".

Digital signatures work in two steps:

- First, you take a message (in this case, our transaction), and using what's called a private key, you produce a signature.

- Afterwards, anyone can take the signature and an associated public key, and check that the signature is valid.

Regardless of how the sign and verify algorithms work (for more information, check this other article), notice that there are two keys associated with Alice: a private (or secret) key, and a public key.

Alice needs her private key to sign. If this key is shared, anyone holding it could produce signatures in Alice's name — sort of impersonating her. For this reason, private keys cannot be shared (which is clearly reflected in their name!).

Both keys are intimately related: the public key can be obtained from the private key, but not the other way around. Similar to hashes, the process is irreversible in practice. This means that the public key can be shared with anyone without fear of losing your funds.

So, what makes Alice be Alice? From her perspective, the ability to sign her own transactions — this is, her private key. And from the perspective of anybody else, the ability to verify her transactions — which is given by her public key.

When Alice transfers a coin to Bob, she sets the receiver to be Bob's public key (or actually, his address — we'll talk about that in a minute). Of course, Bob holds his own private key, and he can now sign a transaction to transfer the coin he just received.

In short:

Identity on the Blockchain is given by public keys, which are a reflection of private keys, which in turn are the gadget that allows users to sign their own transactions.

Addresses and Wallets

Often times, we don't talk about private and public keys. More commonly, the terms we use are addresses and wallets. Let's talk about those!

An address is tightly related to a public key — and it's the standard way to identify a user or an account.

We'll go into much more detail of how addresses are calculated (or derived) later on in the series. It's a really interesting topic, which involves a series of cryptographic operations. For now, just know that an address is associated to a public key, which in turn is associated with a private key.

Lastly, a wallet is a term we tend to use interchangeably with either of the three terms above. We normally never say "transfer to this public key" — instead, we say "transfer to this address" or "transfer to this wallet". Technically speaking, a wallet is some piece of hardware or software that manages private keys, but over the years, it has evolved into almost being the same as an address.

I want to clear a common misconception from the get go: wallets do not hold money. The "money" in a Blockchain is just a value associated to an address — we could say that it lives on the Blockchain. A wallet is just the ability to transfer funds.

Alright! Hope that wasn't terribly confusing. In the end, this is all about signing and verifying. There's a saying in Blockchain which goes:

Don't trust, verify.

As we go deeper into the series, this will gain more and more relevance. For now, it translates into "no transaction is acceptable if it's not signed by the sender".

But wait… We were just sending a single coin, right? What if we want to send more?

Modeling Money

Transferring a single coin was an intentional gimmick for us to focus on transaction signatures.

Let's now relax our restrictions, and allow users to have multiple coins (this is, a balance). We must now be more thorough with our model.

In your bank of choice, you usually have an account with a single balance. Transferring money from this account results in a lower balance, and that's pretty much it.

This approach is known as the account-based model, where each account has a single balance. Most Blockchains (for instance, Ethereum) use this model.

Bitcoin went a bit rouge on this one, and has a different model for cash. It uses something called the Unspent Transaction Outputs model, or UTXO for short. It's a little weird — so let's try to understand it through analogy.

Unspent Transaction Outputs

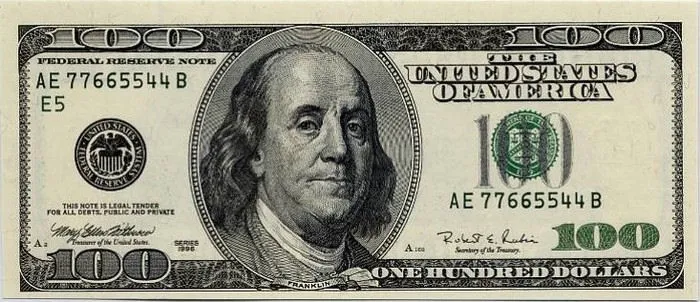

When you spend money in the physical world, you typically use bills. You know, these guys:

Now, if you have to pay for a 40 dollar meal with 100 dollar bill, you expect to receive change. This happens because the bill is indivisible — you cannot tear it into two pieces, and give one to the shop owner. It loses its value. The shop owner would probably not be very happy with this form of payment.

This is a limitation of paper money — but hey, we're designing a system from scratch. No one tells us what to do. We can break bills if we want to. Let's break some bills.

In Bitcoin, the "bills" are what we call the Unspent Transaction Outputs. And just like bills, they have an associated amount.

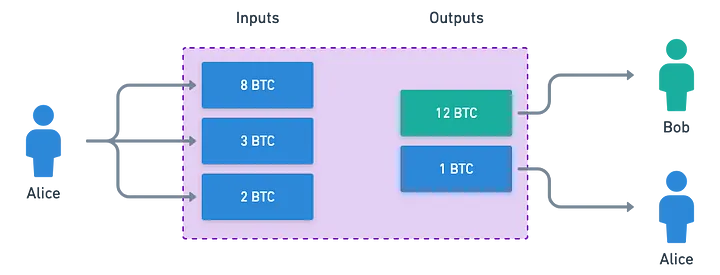

When Alice wants to send some Bitcoin to Bob, say 12 Bitcoin (woah woah, that's a lotta money you got there girl), she may not have a bill for exactly that amount. Her balance is actually composed by multiple bills with different values. Suppose she has three: one for 8, another for 3, and another one for 2.

Just to clarify: 1 Bitcoin is not the minimum amount you can transfer. I just wanted to use simple numbers, that's all!

Alice could then pay in this way:

- Put all the bills in a box. The box has a total value of 13.

- Make the box produce two new bills, one for 12 to Bob, and one for 1 to Alice.

As long as:

- the inputs are marked as spent (or destroyed),

- Alice owns all the inputs,

- the total value going in and out of the box is the same,

then this mechanism is completely valid! And you know what? This box is exactly how Bitcoin represents transactions!

I hope you can appreciate why the fancy name — you can only spend bills that are the output of some transaction, so they are Unspent Transaction Outputs!

UTXO vs Accounts

At this point, it's only fair to ask why the heck we'd use this model. Don't worry, we've all been there.

One reason is that in account-based models (such as your local bank), order matters. If you have a balance of , and you try to pay to Alice and to Bob, one of those transactions will fail. It's important to keep track of which transaction the Blockchain should process first.

Blockchains such as Ethereum do need to keep track of the order of transactions.

The UTXO model avoids this by design: you just select which bills to spend. Once a bill goes into a transaction, it's gone. Boom. It cannot be used again. No need to keep track of the order of transactions!

There are other differences we could mention. For example, in the accounts model, the balance information for a user is located in a single place — its account. And on public Blockchains, this information is available to everyone! UTXO obfuscates this information, because the total balance of a user is distributed across many individual bills.

Other differences include statelessness and fine-grained transaction control, but I presume this is enough information for now! I suggest reading this article for a more detailed outlook on the topic.

Summary

In this installment, we learned how users are identified in the network, and how transactions should be formulated. Neat!

These basics ideas will be more or less applicable to every Blockchain, so it's very useful to wrap our head around these concepts.

We now know how to create transactions… But what happens afterwards? How do we submit a transaction to the Blockchain? Once submitted, how is it processed?

These are all questions we'll try to answer in our next encounter! Stay tuned as we explore the way the network processes and agrees on transactions — what we call the consensus mechanism. See you soon!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.