Blockchain 101: Parallelizing Execution

This is part of a larger series of articles about Blockchain. If this is the first article you come across, I strongly recommend starting from the beginning of the series.

Thanks to the previous installment, we have more than doubled our knowledge of existing paradigms in Blockchain system design. Slowly but surely, our stash of ideas and concepts is growing — and with it, our ability to assess the pros and cons of each architecture.

When choosing a Blockchain to use from this wide array of possibilities, one of the most important elements to look at is speed. We want our transactions to be processed quickly — and sometimes, we’re willing to sacrifice other aspects like decentralization in favor of better processing times.

But ideally, we’d want to sacrifice as little as possible. So today, we’ll talk about some modern approaches that present new and fresh alternatives to this old problem.

Buckle up, and let’s get straight to it!

Parallelization

Before we dive any deeper, I think it’s worthwhile to be understand the concept of parallelization. We’ve mentioned it a couple times, but haven’t been very precise about it. I believe now is a good time.

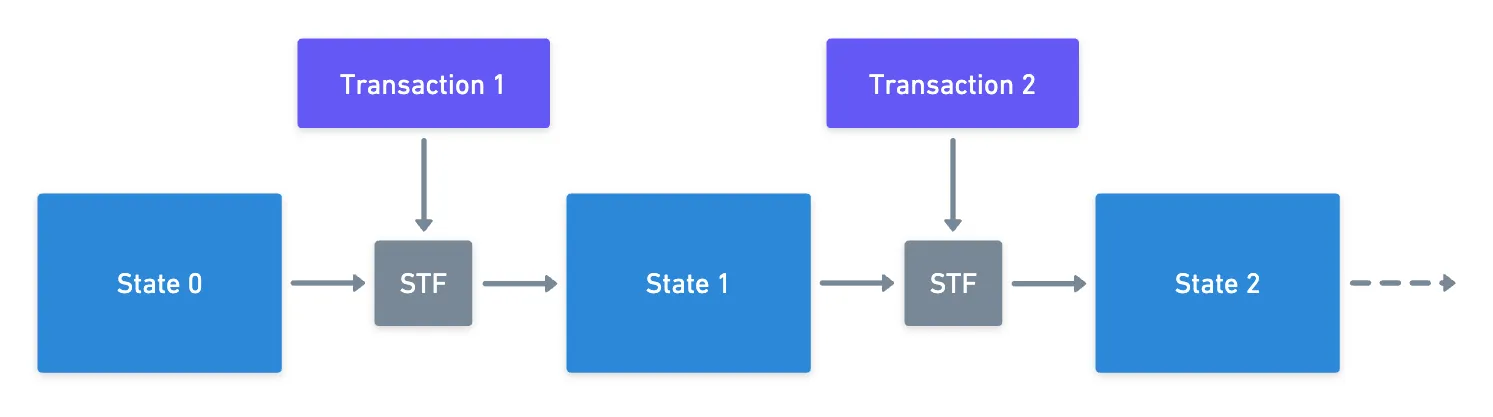

Every Blockchain goes through multiple phases to advance the global state: transaction validation, consensus, execution, and also possibly finality.

Today, we’ll talk about parallelization in the context of the execution phase: the actual computation of what happens when transactions run.

It’s important to note that other processes in the system could be parallelized as well, but we’ll leave that discussion for a later article.

There are essentially two ways to go about execution: we can either process transactions one by one, or try to execute multiple of them at the same time.

Sequential (one by one) processing has one clear benefit: we ensure that no conflicts exist. And this is great, because we won’t end up with a mess of an inconsistent state.

So for example, I can’t transfer an NFT to account , and then transfer the same NFT to account . It wouldn’t make sense, because after the first transaction, I no longer own the asset! This is the old double spending, and we need to avoid it at all costs — but other such situations may exist.

Sometimes though, two or more transactions can be completely independent, in the sense that they wouldn’t conflict with each other, even if executed at the same time. That’s the idea of parallelization: calculating this new state of the Blockchain by executing multiple transactions at once.

At this point, I guess it’s important to ask ourselves: how important is parallelization anyway? Should we care about it?

Performance Bottlenecks

Well, as I briefly mentioned in the introduction, high processing speed is very important for Blockchains to achieve.

How fast we can execute transactions directly impacts the network’s speed. Of course, this is only one of the components that comprise the overall “speed” of the network (as consensus and validation are still necessary), but it’s an important one, since every node needs to execute transactions to determine whether they are a valid state transition or not.

Still, because the overall consensus has various steps, ideally we’d want to identify where the bottleneck is, and try to focus our efforts into optimizing said step. For example, in Ethereum, the most critical part of consensus is attestation aggregation. It’s important to always look at the bigger picture!

Achieving high processing speeds is challenging if we’re only allowed to execute transactions sequentially — so why not just execute everything in parallel?

The thing is, it’s not always easy to determine if multiple transactions are truly independent from each other.

If we look at the paradigms we’ve already explored, account-based Blockchains such as most EVM-based ones have a harder time figuring out this independence, so they choose not to execute transactions in parallel, and they go for the sequential approach. Even Solana, which has some degree of parallelization thanks to the separation of logic and state, has its limitations.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have UTXOs, which are much better suited for parallelization. Each UTXO is a completely independent and immutable piece of state, which is only ever meant to be consumed. This is great, but makes adding logic into the mix complex — and while some solutions like Cardano have proposed improvements, they still have other limitations of their own.

Therefore, the question for today is: what else is there to do about it? And this is where some ex-Meta engineers enter our story.

The Diem Project

Back in 2019, Meta (then Facebook) announced an ambitious project: a global digital currency called Diem (originally Libra).

Not the same Libra from the Twitter scandal a few months ago!

They set out to create a Blockchain that could handle billions of users with the speed and reliability of traditional payment systems.

At the time, this was truly challenging: existing Blockchain architectures simply couldn’t handle such a scale. Even the fastest Blockchains at the time (probably EOS and Ripple, handling a few thousands transactions per second) would crumble under the load these Meta engineers were trying to cater for — the load of Facebook’s user base.

So they decided to start from scratch. In doing this, they didn’t just build a new Blockchain — they built a new programming language, specifically designed for digital assets and parallel execution. This language was called Move.

You can learn Move with the very detailed Move Book.

More than the language itself, what we need to focus on is how it proposes a new way to think about Blockchain state: digital assets are treated as resources rather than data in accounts. Literally, you own distinct digital objects that can be moved around and modified.

Why is this important, you ask? Well, if every asset is a distinct object with clear ownership, then transactions involving different objects can be processed in parallel without conflicts!

It was a really promising prospect... Until, in an unfortunate turn of events, the Diem project crumbled under regulatory pressure in 2022, and was shut down.

From the Ashes

It could have ended there, and I’d probably not be writing about this today.

Luckily, the engineers behind these ideas were convinced they were onto something, and decided to push through the hardship. Instead of quietly going down into the night, they scattered and formed new projects, taking their learnings with them.

These projects are now called Aptos and Sui, and will be our protagonists today.

Aptos

Let’s start with the earliest one to launch: Aptos.

This first team didn’t stray too far from the ideas we’ve explored so far: Aptos is a Blockchain built with the familiar account-based model in mind.

Yeah, our trusty old friend!

But wait... Didn’t we say like 2 minutes ago that the accounts model wasn’t good for parallelization? And wasn’t Move all about replacing accounts with resources? What’s the catch?

Well... Aptos uses accounts, that’s a fact. It does leverage Move’s type system for better state management, but that’s more of a developer experience detail.

Having said this, we know for a fact that an accounts-based system will have problems with parallelization. Conflicts will happen, and a rich typing system will do little to mitigate this.

Think about it: if both Alice and Bob try to send money to Charlie’s account at the same time, there’s going to be a conflict. It doesn’t matter if we call Charlie’s balance a “resource” or simply “data” — two transactions are still trying to modify the same thing simultaneously.

So how does Aptos achieve parallel execution?

Optimistic Parallelism

Aptos’ solution is simple in concept: instead of trying to prevent conflicts, it embraces them.

When a set of new transactions arrives, Aptos doesn’t carefully analyze which transactions might conflict and process them sequentially. Instead, it takes an optimistic approach: it simply executes all transactions at the same time, assuming most won’t step on each other. A small leap of faith.

Now, I bet your spidey senses are tingling: what happens when conflicts do occur?

Aptos uses an execution engine they call Block-STM (Software Transactional Memory). This system is constantly monitoring for these conflicting situations. When it detects that two transactions have tried to modify the same account, all it does is roll them back, and re-execute them in the correct order.

Kinda like having a smart undo functionality. As simple as that!

When most transactions in a block are truly independent (the best-case scenario for this execution strategy), Aptos can achieve amazing processing speed improvements, because the execution is truly parallel. However, there will also be worst-case scenarios where many transactions conflict. In that situation, the system operates closer to sequential processing due to all the rollbacks and re-executions.

The interesting consequence is that this approach is adaptive. And under the right circumstances, the network will be lightning fast.

I find it wonderful how such a property emerges from the simple choice of executing transactions in an optimistic way!

Sui

Let’s now switch gears, and talk about Sui, the other project born from the ashes of Diem.

While Aptos decided to keep the familiar account model and make it work with parallelization, the Sui team took a completely different approach. They decided to redesign everything from the ground up for maximum parallelization.

And their design was quite radical: Sui doesn’t use accounts at all.

Objects to the Rescue

In Sui, everything is an Object. Your tokens? Objects. Your NFTs? Objects. Smart contract state? Yeah, Objects.

Sui’s objects are essentially the fully realized resource model originally envisioned by Move!

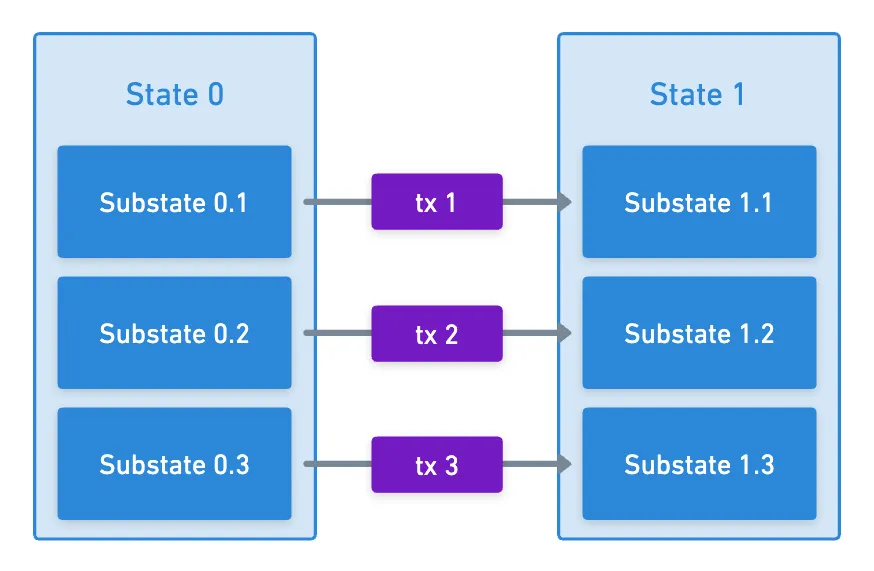

Using objects has cool benefits for parallelization — but first, we need a rough idea of what they are. And for this, let’s compare them with the models we already know: account-based, and UTXO.

- An account may be the owner of multiple Objects, that in conjunction represent its overall state. Therefore, this is a finer or more granular type of representation than the accounts model, and it’s easier to determine when two objects are independent from each other.

- When compared to UTXOs, the difference mostly resides in mutability. UTXOs can be thought of as a type of immutable object (which can only be created or destroyed), while Sui Objects are generally mutable (with the exception of native immutable objects).

So in a way, Objects represent a sweet spot between these two other models!

UTXOs offer nearly perfect parallelization (in terms of execution) but are too rigid — you can only consume them, never modify them. Accounts are flexible, but create bottlenecks since multiple types of assets share the same account space. Objects give you the best of both: they’re flexible like accounts, but independent like UTXOs.

And the cherry on top: transactions in Sui declare exactly which Objects they need upfront — and thanks to their granularity, the system immediately knows whether these transactions can run in parallel!

If Alice’s transaction uses Object A and Bob’s transaction uses Object B, then they can run simultaneously without any conflicts!

In terms of ownership, Objects can either be:

- Owned objects, owned by a single account

- Shared objects, and accessible by everyone

- Immutable, and cannot be modified by anyone

- Owned by other Objects, enabling composability

More about this in the official Sui documentation.

Most Objects in Sui are owned Objects. And if everything we’ve said wasn’t cool enough, this has another powerful consequence: transactions involving owned Objects only can be executed faster than the ones involving shared Objects!

Sui actually uses two different types of consensus depending on what your transaction touches. For owned Objects, Sui only needs to check that your transaction is valid — this is, that you own the Objects, and that you’re not double-spending. Once enough validators agree your transaction is valid, then boom — immediate execution! No need to wait and see what order it should go in relative to other transactions.

Shared Objects require a more careful treatment, because multiple people might try to modify the same Object at once. Sui first needs to decide the order of transactions through its Mysticeti consensus mechanism.

As a result, simple transfers and payments happen in under half a second, while more complex shared-state operations may take a bit longer, but still work efficiently. Most simple Blockchain operations (like sending tokens) will feel near instant in Sui.

Granted — you’ll need to think slightly differently when designing applications in Sui, but if you’re willing to put in the time and effort, it is a fast Blockchain indeed!

Both approaches represent different philosophies. Aptos proposes making the familiar model faster, while Sui rethinks the model entirely. Neither is universally better — it depends on the specific use case.

For simple transfers and payments, they both excel. But for more complex protocols and logic definitions, where lots of shared states are used, then things may get complicated. In Aptos, performance may take a heavy hit. In Sui, designing these applications may become overly complex, and more prone to errors.

And again, there are no perfect solutions!

Summary

The remnants of the Diem project certainly left something interesting for the Blockchain ecosystem: two very different and rich approaches to parallel execution.

In particular, this object-oriented architecture is a valuable addition to our set of design patterns, as it happens to be an excellent midpoint between existing paradigms (UTXO and account-based).

Both Aptos and Sui represent a significant advance in improving execution speed, but they’re not the only new kids in town. The Blockchain space is full of innovative approaches, each taking different philosophical and technical paths.

Some projects focus on parallelization within a single chain, like we’ve seen today. Others ask entirely different questions.

Thus, in our next encounter, we’ll start working through these new spicy questions, which will lead us to some very exotic solutions.

Cheers!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.