WTF is RISC-V

Lately, I’ve been hearing about RISC-V a lot.

From being quite useful for modern cryptography and embedded systems, to strong economies heavily investing into the technology, RISC-V seems to be everywhere, and looks poised to become a new big player in the market.

As such, it’s wise to at least try to wrap our heads around the concept. In my case, this is one of those things I’ve neglected for quite some time — and while I felt I had a grasp on the subject, my every attempt at explaining anything about it ended in a miserable failure.

So today, I’d like to dedicate this article to exploring what this technology really is, what it brings to the table, and how it might affect the systems we know and love.

However, this story cannot start at RISC-V. First, we need to understand a couple things about how computers work.

Computers Under the Hood

It’s hard to imagine life without computers around, isn’t it?

I mean, they are everywhere, and help us in many ways — from simple aids to day-to-day chores, to highly sophisticated tasks like simulating complex structures or helping develop new medicines.

Or, you know, for your own amusement when requesting your GPT of choice to Roast You.

What I find perplexing is how these diverse functionalities arise from very simple building blocks. Logic gates are laid out in such a way that memory units can be created, which in turn allow us to perform complex and programmable operations.

In this last regard, we must stop and focus on the key component in computers that makes it all possible: the Central Processing Unit, or CPU.

The CPU is essentially the brain of any computer. It’s a component capable of receiving and executing instructions, which when correctly sequenced, can express an extraordinary amount of different behaviors.

These sequences are what we’d normally call programs.

But here’s the thing: they can only understand very specific and actually quite simple instructions. You can’t possibly ask them to do things such as “play this video”, but you can require them to add two numbers together, or move some data from one place to another.

When we design a CPU, we must establish exactly what these instructions are, and these will be the tools that us developers will have to create programs — or to instruct the CPU to perform the calculations we need it to perform.

Although, this usually happens behind the scenes. Seldom do we write these instructions directly. More on this further ahead!

A set of instructions is called an Instruction Set Architecture (or ISA for short). And this is at the center of today’s discussion, because the choices we make when design it will have sizable consequences down the road.

Designing an ISA

Let’s suppose for a moment that we know nothing about existing ISAs, and we want to come up with a reasonable set of instructions with which we can do just about anything. How would we approach this problem?

We already mentioned a couple evident things, such as adding numbers together, or moving data around. Other obvious candidates might include subtracting, multiplying, and dividing numbers. We’d probably want to compare values — you know, checking if one number is bigger than another, or if two values are equal.

But then, things might get trickier. What about more complex operations? Should we have a single instruction that can, say, calculate a square root? Or do text manipulation? What about something as complex as sorting a list of numbers in one go?

Admittedly, that last one is almost absurd and I think no ISA includes an instruction for that!

This very quickly becomes a complicated design puzzle. And as previously foreshadowed, the decisions we make have important consequences. You see, the more instructions we want to support, the more complex the CPU will need to be in order to interpret them.

This translates into:

- More transistors

- More manufacturing costs

- More power consumption

- And generally speaking, more opportunities for things to go south

On the other end of the spectrum, if we have too few instructions, we might not be able to do certain operations. Even if our set is expressive enough, our programs become longer, as we’ll need many simple instructions to accomplish what one complex instruction could do.

And while this kind of CPUs are easier to build and optimize, longer programs might lead to more errors!

All in all, this feels like a balancing act — one in which we need to be very mindful of our decisions.

Luckily though, we don’t need to solve this problem from scratch.

Design Philosophies

The problem we described is actually a very tough one.

It’s a complex mathematical optimization problem, where our pondering of costs and proneness to error might affect our end result.

In other words, there’s no single optimal solution. Instead, what people have done historically is come up with good rules of thumb (heuristics) to design ISAs, which have developed into two main philosophies:

- The first approach proposes to make the instructions as powerful and comprehensive as possible (without losing generality). This is called Complex Instruction Set Computing, or CISC.

- In contrast, the second approach seeks to keep the instructions simple and fast, in what’s called Reduced Instruction Set Computing, or RISC.

Yeah, exactly — that’s the RISC in RISC-V!

With this panorama, we’d tend to think there’s no clear winner here, as both systems have their advantages and disadvantages.

However, the market has told a different story for many years.

Market History

The CISC philosophy championed the market for quite a long time.

It might not be evident why the longer and more complex instructions of CISC would be useful, but there’s actually a really good reason: memory.

Our programs (again, sequences of instructions) have to be stored somewhere in memory in order for a CPU to execute them. And when computers started populating homes in the 70s and 80s, memory was costly and scarce.

Of course, a shorter program meant less memory was needed. Since a CISC architecture could pack lots of functionality into shorter programs (and thus, shorter sets of instructions), this meant significantly reduced manufacturing costs, and a genuine economic advantage.

This led to another factor for the popularity of CISC: software compatibility.

Intel quickly established x86 as a standard. As a consequence, most programs were tailored-made for this architecture. So if for some reason you wanted to use a different ISA, you’d have to rewrite all your existing software (programs).

And you can imagine that businesses who had invested millions into developing programs that ran on x86 weren’t going to lightheartedly abandon their investments!

As a consequence, CISC had a firm grasp on the market. Even as memory became cheaper and RISC’s advantages became clearer, customers kept using CISC processors. The market was locked because everyone depended on the same standard.

Time went by, and memory became cheaper. New markets also emerged where a RISC could shine — for example, mobile computers (aka your smartphone) required more efficient processors so that they could run on batteries, and massive server farms (with the advent of the Internet) were very concerned with keeping energy costs down.

Naturally, RISC quickly dominated the market in these areas. And again, a few companies swiftly set standards that locked customers into their technology once more. So while the resurgence of RISC was very interesting from a technological perspective, it seems clear that there was another problem.

Both markets suffered from the same fundamental conundrum: whoever controlled the ISA, controlled the market.

It’s essentially an issue around proprietary control. If you wanted to use a particular architecture, you had to play by the rules of its owner, pay their licensing fees, and also hope they didn’t suddenly make impactful changes.

That was the context and the tension that ultimately motivated the development of an alternative.

RISC-V

It’s pronounced “risk-five”.

RISC-V was originally developed in Berkley in 2010, motivated by a single idea: what if the building blocks of computing weren’t owned by anyone?

I mean, it sounds almost absurd to put it that way — but the market reality clearly suggested otherwise.

Thus, RISC-V is completely open source. Anyone can use it, modify it, or build processors based on it without paying licensing fees or asking permission.

However, the attractiveness of RISC-V isn’t only on its usage policies — it was designed from the ground up to be modular and extensible.

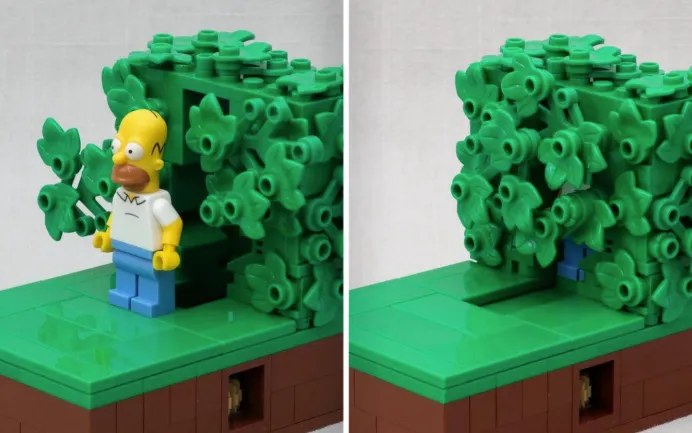

What do I mean by this? Well, first of all there’s a base instruction set which is minimal by design. As in, just enough to run basic software. From there, you can add standardized extensions to fit specific needs, like floating-point arithmetic, vector operations, and even cryptography.

Much like legos for CPUs. Although Lego is proprietary... But you get the point!

Modularity solves a problem about existing solutions that we actually haven’t addressed yet: bloat.

Over the decades, proprietary RISC and CISC architectures have gone and accumulated hundreds of instructions to satisfy many different use cases. As a consequence, your smartphone’s processor carries instructions for some situations it will never encounter. And your laptop might carry legacy instructions from the 80s that modern software hardly ever uses.

After all, becoming the standard means you need to cater for all sorts of applications and markets!

With RISC-V, you only include what you need, which directly translates into smaller and more efficient processors for specific applications.

Okay, this sounds very promising.

There’s a small problem though: we usually don’t write programs in ISA language, but rather choose some programming language, and use it to craft our programs.

Unless you’re a madman and like to write programs directly in CPU instructions.I know some friends which would deeply enjoy that — but perhaps they could benefit from a visit to a psychologist as well.

So, can I just write a C++ program that runs on RISC-V? How would that work?

Compilers

This is where compilers come into play — and this is one of RISC-V’s biggest success stories.

A compiler is essentially a translator. It takes programs written in your typical high-level languages — C, Python, or Rust —, and converts them into the instructions that a processor will understand.

Of course, different processor architectures need different compilers, to generate the right set of instruction. This seems to be somewhat problematic: since RISC-V is modular, the set of instructions depends on what modules you choose to use!

But actually, this is no problem at all — the modularity offered by RISC-V can even make the compiler’s job easier. Since the set of instructions is clean and well-structured, compilers can be told exactly which extensions are available on the target processor, and take advantage of any specialized instructions to make your code faster.

Today, all the major compiler toolchains (like GCC, LLVM/Clang, etc.) support RISC-V. This means that if you have a program written in C, C++, Rust, or one of many other languages, you can compile it to run on RISC-V processors with minimal or no changes at all to your code.

This support is actually crucial for RISC-V’s success — it means it doesn’t have to start from zero. Existing software can potentially run on RISC-V without much of a problem.

If you recall, this was one of the main reasons for the market dominance of proprietary architectures!

Real-World Uses

So, is RISC-V being used? Where?

As of late, adoption has been fast — perhaps faster than many expected. Driving this celerity are both economic and geopolitical reasons.

On the geopolitical front, China has been investing heavily on RISC-V development as part of its strategy to reduce dependence on Western chip architectures. Trade tensions and political disagreements can cut off access to critical technologies in the blink of an eye — so having an open standard might become a critical strategic factor, or even a matter of national security.

Not everything is geopolitics, though. Major tech companies have gotten their feet wet with RISC-V as well. Google experimented with RISC-V for Android devices for a while, while companies like SiFive (which was founded by RISC-V’s original creators) are already building commercial processors.

The Blockchain and web3 industry is also taking notice, and slowly bringing RISC-V into the game. As we know, efficiency is king in these systems for scalability to be a thing, which means fertile soil for this new technology.

Related to this, zero-knowledge proving mechanisms are also being built around RISC-V, which promises to make them more efficient and versatile.

And there are some more case studies you can check out in the official page.

Summary

We’re still in the early stages, but RISC-V has certainly picked up steam, and it’s definitely a worthwhile alternative to explore in the right scenario.

I think with this, you should be leaving this article with a good idea of what RISC-V is all about — and a little extra about computers as well.

Now, whether you should care about this or not really depends on your own curiosity, and what your projects are about. You don’t necessarily need to start building modular CPUs, or care about compiling your programs to specific ISAs.

Actually, I’d dare say that most of us mortals won’t be playing with this stuff anytime soon.

But the technology is there, slowly crawling its way into our systems. Who knows — it might be a matter of time before you’re reading this on a RISC-V powered device.

Only time will tell. Better be prepared!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.