WTF is the Internet

I reckon this article might look a bit out of the ordinary. So to give you some context, I want to start this with a little story.

My first approach to programming was to make simple games in Flash, using ActionScript.

I bet some of y'all might remember those good ol' days.

I hadn't had any formal education in computer science at that time, so when I tried my hand at web development - which was not as easy 20 years ago as it is today -, I found many things hard to understand. In particular, I didn't quite understand how the Internet worked.

But I ended up focusing on the development part, not paying too much attention to what happened in the background. Because hell, why do I care how the Internet works, if I'm only trying to build a webpage?

Fast forward around 15 years, and I decide to shift my professional career into software development - again, like many people have done in the recent past. What I found was that I had lots of questions and insecurities.

You know, the typical case of imposter syndrome.

If I was going to succeed at this new gig, I needed to understand the basic principles of software development. And here I was, again, wondering how the heck the Internet worked, and how much I needed to know to become a good professional.

My intuition tells me that some of you might relate to this personal experience.

Therefore, this article is for those of you who are still a bit puzzled about this topic, and perhaps want to fill in some knowledge gaps.

And I can only speak for myself here, but I know it would have helped me to read this a couple years ago.

So yeah! I think there's a lot to gain from shedding some light into what happens under the hood - not only to understand the processes happening when we visit a website, but also to correctly assess the challenges and problems we might encounter when building software.

Let's go!

First Steps

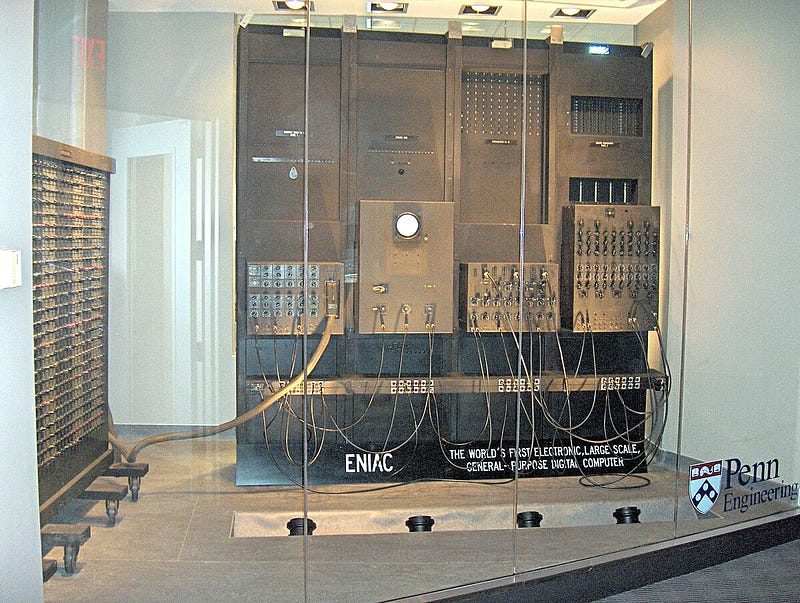

Back in the 1960s, computer science was still in its infancy. Computers were nothing like the small-yet-super-powerful devices we can now hold in the palm of our hands. Rather, they were these chunky carcasses that you'd never expect to find in any normal household.

Access to these machines was of course limited. And computing time was an appealing new resource, mostly for researchers. The name of the game was the ability to do time-sharing: allowing many tasks to be executed by a single computer at the same time (concurrently).

The computer equivalent of multitasking.

However, there was no defined way to execute tasks at a distance. This might seem hard to believe because nowadays, we can have real-time chats with people on the other side of the globe - but this wasn't always the case!

So, one of the big research topics at the time was how to transmit execution instructions over long distances. The world had already seen the telegraph by that time - so it wasn't an unachievable feat.

It was more a matter of efficiency. In other words:

![]()

![]() How do you efficiently send information across long distances between computers?

How do you efficiently send information across long distances between computers?![]()

![]()

This was the question to answer for researchers at the time.

Packet Switching

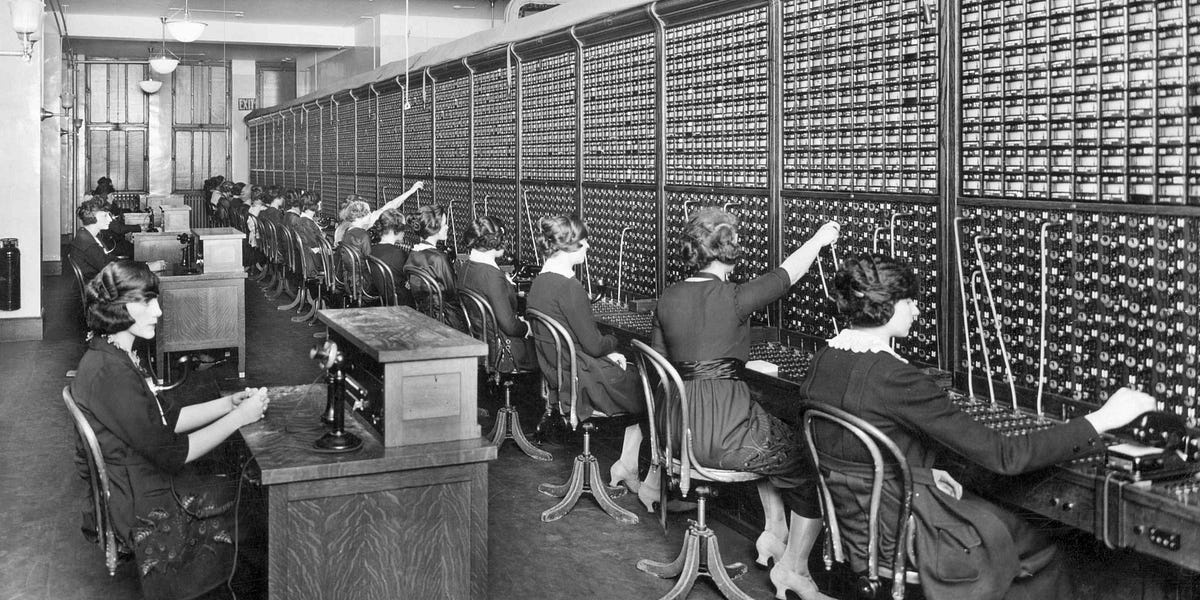

Much like the telegraph, another invention that was really well-established at the time was the telephone. Traditional telephone networks used what's called circuit switching: a dedicated, physical connection was created between two points for the entire duration of a communication.

That's exactly what we see in contemporary movies - people plugging cables in switchboards on demand.

This worked fine for voice calls, but was very inefficient for computer communications, which tend to happen in bursts.

When you load your Instagram feed, you normally do an initial "heavy" loading, and then the app becomes "idle" and waits for your interactions before requesting more information. While some things may happen in the background, the general flow mostly works like that.

It's not very efficient to have to create a dedicated cable connection for each burst of information. A different approach was needed.

The solution came by sort of inverting the problem: you build a static highway of connections between different devices, and instead of having the information go through a direct path, you allow it to take any route - as long as it reaches its destination, we should be good!

Much like Amazon delivering your goodies - they have the package's origin, destination, and they decide what route to take for you.

This is what's called packet switching. It was a revolutionary concept back in the day, developed independently by computer scientists like Paul Baran and Donald Davies in the early 1960s.

Data is broken apart into small chunks, called packets, each containing information about where it came from, and where it's headed. These packets travel through a network, taking different routes, and then get reassembled at their destination.

Neat, right?

The only problem is that we need a network - the highways over which these packages travel. And that infrastructure did not really exist yet!

ARPANET

Luckily for us, this packet switching idea was not shelved. Instead, the required infrastructure was created to put it to good use.

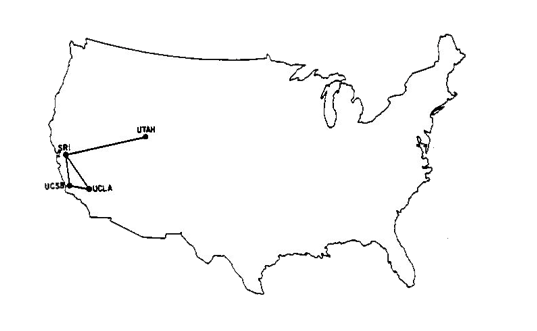

In 1969, Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) created the first packet-switched network, and dubbed it (drum roll please) the ARPANET.

Yeah... Us engineers are not known for being most creative people out there.

Initially, it just connected four research institutions, but this was enough to demonstrate that the packet switching technology worked.

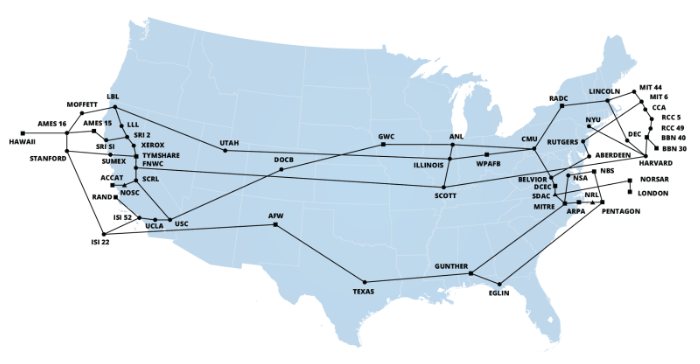

Over the next decade, more and more institutions started plugging into ARPANET. Slowly but surely, it started growing large.

A larger network was pretty cool - because it enabled communication with many more computers. However, this came coupled with another problem.

You see, with only four institutions that were relatively close distance-wise, researchers could agree upon how to identify each other, and the format of the messages they exchanged. As computers and institutions were added to the network, they needed to be identifiable by other existing computers, and they needed to sort of follow some rules to correctly send packets from one location to another (packet routing), and for other computers to understand their messages.

But what rules? Who defines how to do things?

In order for everything not to become chaotic, some sort of standard was needed. A well-defined set of rules to follow. A protocol.

The Rules of the Internet

Question time: what do you think happens when you navigate to a website on your browser?

Well, to be fair, quite a few things happen - but most importantly, your browser is pulling a bunch of files from another computer somewhere in the world.

It's common to talk about "the cloud" nowadays, but of course, websites are not just floating around in the ether - they are a combination of files stored somewhere, precisely delivered to your screen.

This means at least two things: that we need to correctly identify both the source and destination computers, and that we need a way to ensure that packets or datagrams are effectively sent from the source, and into our screens. And that's how the Internet Protocol came to be.

The Internet Protocol

Think of a post office delivering cards. Obviously, they expect each card to have an address in some sort of common format, like . Other combinations of things might feel weird, and the delivery service wouldn't really know what to do with them.

Let's start with the simple part -** identification**. Much like real addresses, IP addresses became the way to identify computers that would connect through the network.

The most common type of address is the IPv4, which looks like this:

![]()

![]() 172.16.254.1

172.16.254.1![]()

![]()

What we're looking at is just a 32-bit number, divided into 4 sections of 8 bits (a byte), separated with dots, and in decimal.

This is - a nice and convenient way to represent a number between and .

That number () is actually not that big. It's about 4 billions. Statistical and market analysis estimate that the number of computers and personal devices exceeds that mark, which is quite alarming, because it would mean that IPs are not unique!

I mean, this is to be expected of a standard defined in 1983 - it was hard to foresee the level of mass adoption at the time, I guess.

Although there are some workarounds - like Network Address Translation (NAT), which allows multiple devices to share a single IP address - , this limitation led to the development of IPv6.

IPv6 addresses look like this:

![]()

![]() 2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334![]()

![]()

That's a lot less friendly-looking than IPv4 - but under the surface, it's just another way to present 128 bits. And a grand total of approximately 340 undecillion unique addresses (that's 340 followed by 36 zeros).

To put that in perspective, we could assign an IP address to every atom on the surface of Earth and still have plenty left over.

Adoption of IPv6 has been really slow, and today, both IPv4 and IPv6 coexist. Yeah, updating the internet is hard. Who would have thought?

Routing

Now that we have our computers identified, we need to ensure packets get to their destination. But remember, the Internet is essentially a graph of connected systems (a network), and our packets probably need to make a few stops along the way.

This is where IP routing comes into the scene. Routing is actually quite simple: it's like asking for directions. Whenever a packet reaches a router, it basically asks: "How do I get to this destination?".

Routers are specialized computers whose main job is directing traffic. Intersections in our internet highway, with those big green signs telling packets which exit to take.

Your home router is where your personal network meets the broader Internet - the on-ramp to the information superhighway, if you will.

Two ingredients are required in order for this to work:

- This router thingy needs to be able to understand where the package is headed, and

- It also needs to know where to direct it.

The first part is easy: again, we rely on standardization, and have our packets contain a header with some crucial information - like where it comes from, where it's headed, the package's length, and a few more things.

All bundled in what we call an IP packet.

It is the second part that's not that straightforward.

You see, if every router had to keep a list of all other routers and who they are connected with, we'd run into problems quickly. For one, the sheer amount of information (of all networks in the world) would require too much memory.

Not to mention that this list is highly dynamic - it changes all the time. Keeping every router updated all the time would simply not be possible: the Internet would spend more time gossiping about network changes than actually moving data.

What do we do then?

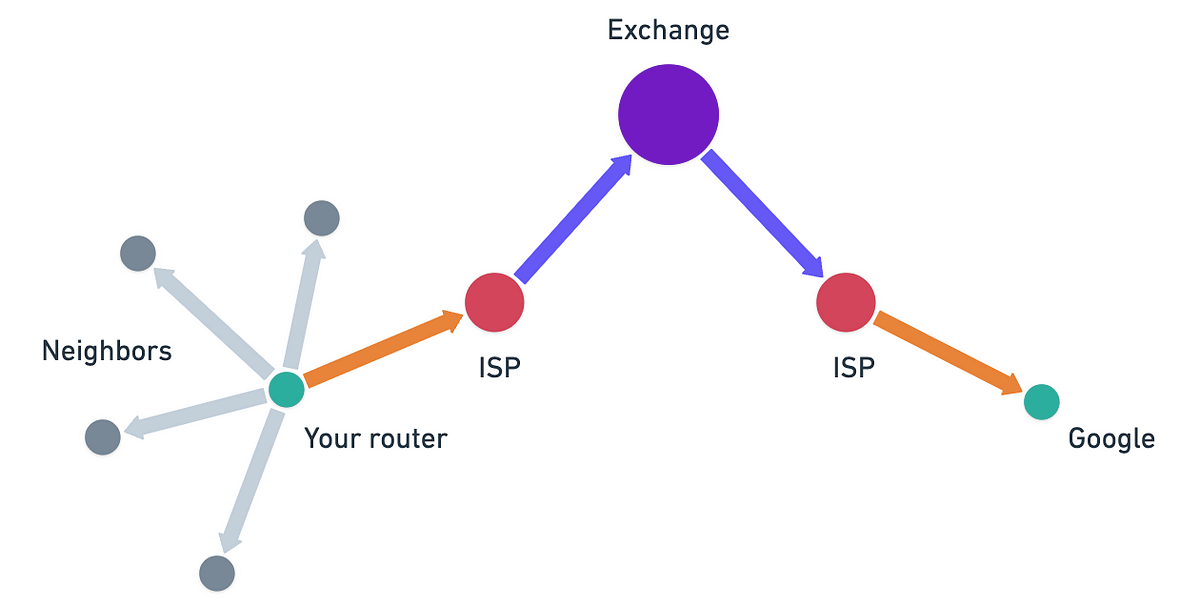

The Internet uses a clever approach: hierarchical routing. An example will help here:

Imagine you want to send a letter from your hometown to someone in Japan.

Your local post office doesn't need to know the exact layout of every street in Tokyo. It just needs to know to send international mail to a regional sorting facility, which knows to send it to the international hub, which knows to send it to Japan, and so on.

Routers work similarly. They keep routing tables that contain information about:

- Networks they're directly connected to (neighboring connections)

- Which neighboring router to hand packets to for distant destinations

For example, your home router doesn't know how to reach Google's servers directly. It just knows to send all "not-local" traffic to your Internet Service Provider's (ISP) router. Your ISP's router might know to send Google traffic toward a specific major internet exchange. And so on, until the packet reaches its destination.

This is not only efficient, but it's also a very resilient model. When some connection fails somewhere, only the routers in that area need to find alternative paths and share that information with their neighbors. The rest of the Internet is mostly unfazed by these local disruptions!

Interpreting Information

Okay, so we now know how packets get from one place to another. But remember - our original data was broken into smaller pieces, bundled into these packets, and sent on their way.

Thus, the receiver will not get all the data in a single, tidy delivery, but rather get a mess of chunks that they need to somehow organize into meaningful content.

When loading a webpage, you'd want all the packets to be reconstructed in such a way that the webpage looks good, and not the best effort of someone just learning CSS!

How do they do that?

Short answer: we need more protocols.

There are two main transport protocols at this level: the User Datagram Protocol (UDP), and the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). We'll focus on the latter first, as it's the most widely used one.

Transmission Control Protocol

Sorting packets takes a little bit of extra work. What TCP proposes is this:

- Establish an initial connection: like knocking on the receiver's door, to see if they are home, and ready to receive packets.

- Numbers the packets: each packet receives a unique, incremental packet number, so that they can be put in the correct order by the receiver.

- Receive acknowledgment: the receiver tells the sender "yep, got packet #47" so the sender knows it arrived.

- Lost packet retransmission: If packet #47 never gets acknowledged, the sender will retry sending it.

- Flow control: TCP prevents the sender from overwhelming the receiver with too much data at once.

With these relatively simple rules, we ensure a reliable and ordered delivery of data. No half-loaded pictures of cats. Nice.

Of course, this reliability isn't for free - TCP has overhead. Acknowledging, numbering, and retransmitting take time and bandwidth.

For some applications like video streaming or online gaming, this overhead may become a critical bottleneck - it's better to get new data quickly, rather than wait for old data to be retransmitted. It's in these situations that UDP really shines: it uses a "fire and forget" strategy, which is faster, but less reliable.

Putting It All Together

To start tying things up, let's go back to our original question: what happens when you navigate to a website on your browser?

- Your browser determines the IP address of the server to communicate with

- Through TCP, a reliable connection is established with that server

- Your browser sends a request over that TCP connection

- The server responds with the webpage data

- TCP ensures all the data arrives correctly and in order

- Your browser renders the page

What's quite mind-blowing is that all of these steps typically happens in milliseconds, thanks to decades of engineering refinement.

I've simplified a few details - but I'm willing to bet you still have one lingering question after reading that.

How does your browser know what IP address to connect to, when you typed "google.com"?

The Domain Name System

Right - you type "google.com" or "twitter.com" or "stackoverflow.com" - not some weird sequence of digits. But TCP only understands IP addresses, so we need a way to map those domains to IP addresses.

We could think of these domains as aliases - but the problem is that everyone should agree on the alias to IP address mapping. How do we ensure this mapping is consistent across the vast Internet?

This is what the Domain Name System (DNS) solves.

A.k.a. the phone book of the Internet.

Much like our previous routing problem though, it's not feasible to keep this mapping in every single computer, because of its size, and how often it needs to be updated.

Therefore, the DNS also works in a hierarchical, distributed manner. You first check your computer's cache - a small list of known IP address to domain conversions. If no match is found, the next step is asking your ISP. And if they don't know, they escalate the query to what's called a root name server (also known as just root servers).

There's a grand total of 13 "main" root servers worldwide!

These in turn ask the .com servers, who ask smaller authoritative servers, who finally respond with "this is the IP address for google.com".

And once your ISP learns of the correct IP address, it remembers it (caches it!) for subsequent queries. And so does your computer!

Overall, it's a very clever system.

There's more to it than this short explanation - DNS can be set up in various ways through the use of different DNS records, and they enable cool tricks like:

- load balancing: resolving a domain to different IP addresses.

- redundancy: multiple IPs returned for the same domain.

It does come with some flaws, though: because it was designed in a more "trusting" era, it overlooked some possible attacks. In particular, DNS poisoning can redirect users to malicious sites, and DNS outages can effectively make large portions of the Internet unreachable.

Summary

If this felt like a lot of information, it's because it is.

After all, the Internet is very complex and intricate system. Even after all the things we've covered, there's still much more to learn. For example:

- How exactly is information transmitted in the physical sense?

- What is HTTP, and how do web browsers actually request and receive web pages?

- How does Internet security work?

- What happens (and what can we do) when things go wrong?

- What does the future hold for the Internet?

It's a pretty involved subject - and as I mentioned at the very beginning of the article, depending on what you do or what you're building, you don't really need to know all the details.

Still, I'm a firm believer that there's a lot to gain from trying to understand these complex systems, as they showcase clever approaches to problem resolution that may come in handy in other situations.

And so, the next time you effortlessly navigate to your favorite website, remember that there's an entire global infrastructure, working in mere milliseconds to get you your precious daily articles.

Pretty neat that all this complexity is hidden behind something as simple as typing a URL, right?

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.