Blockchain 101: Polkadot Consensus

This is part of a larger series of articles about Blockchain. If this is the first article you come across, I strongly recommend starting from the beginning of the series.

The previous episode was somewhat of a warmup, so we could start submerging ourselves into the (deep) world of Polkadot.

Up until now, we’ve been talking about Rollups (or Parachains), but we said these lack one crucial functionality we’d expect from any Blockchain: consensus. This is intentional, as consensus is delegated to a parent chain, called the Relay chain.

So today, we’ll start talking about this very much central component in Polkadot’s infrastructure, and its role as the very core of this technology.

Let’s go!

Consensus

From the previous article, we know that each Rollup has the ability to define its own state transition rules, but they alone can’t grow their own Blockchains (Rollups). Sure, they will receive transactions, and even propose blocks, but consensus will be delegated to the Relay chain.

So right off the bat, it seems we’re in a pickle: how can the Relay chain verify the state transitions of Rollups?

And it needs to do so in order to provide consensus, because it needs to ensure the evolution of a Rollup follows its own rules!

Our first instinct should be that the Relay chain must have some kind of knowledge of all existing Runtimes. And that’s exactly right: Runtimes must be registered in the Relay chain for this entire mechanism to work.

But then... If Runtimes are also stored on the Relay chain, how are they different from Smart Contracts? It seems we’re going in the exact direction we set out to avoid!

What is it then?

Collators

The key difference lies in where state lives. Every Rollup keeps track of its own state (and Runtime), so let’s see what happens from their perspective.

How would block production work in a Rollup? Well, some sort of validator (or at least block producer) would need to produce a block with valid transactions, and then it would somehow need to tell the Relay chain something like:

![]()

![]() Here’s a block — I need you to validate it, and tell me once it’s ok for me to add it to my Blockchain

Here’s a block — I need you to validate it, and tell me once it’s ok for me to add it to my Blockchain![]()

![]()

Here’s the deal though: the Relay chain doesn’t know much about the state of the Rollup. Our producer, however, does have this information. So with some cryptographic magic, what they do is provide just enough information for the Relay chain to do its job.

The nodes in charge of producing blocks and providing this information are called Collators, and the information they provide is a short proof called a Proof of Validity (PoV for short).

But what exactly is contained in these short proofs?

Building the Proofs

In theory, there are various ways to prove that a computation was executed correctly. Because that’s what we’re doing: the Runtime is in reality nothing more than a function, which takes a current state and a transaction (also called an extrinsic in Polkadot jargon), and produces a new state. Like this:

Where represents state, and represents a transaction. And the function is the Runtime!

Such a function is usually called a state transition function.

So yes, our goal can be repurposed into proving that the function’s output was correctly computed for a given set of inputs.

There are various proving systems that allow us to do such a thing, namely:

- Zero-knowledge proofs (like SNARKs or STARKs) prove the correctness of a computation, optionally without revealing certain information.

- Fraud proofs, that assume the computation is correct unless someone can prove otherwise.

- Witness-based proofs, that provide just enough data for someone else to verify the computation.

Polkadot opts for the third approach: witness-based proofs, built out of Merkle trees.

The reason for this is that Rollup state, in very similar fashion to Ethereum, is stored as a modified Patricia Merkle trie.

For reference, see here!

The main idea is quite simple, actually: share only the parts that have changed, plus enough information to reconstruct the state root. Yeah... Perhaps an example will help here.

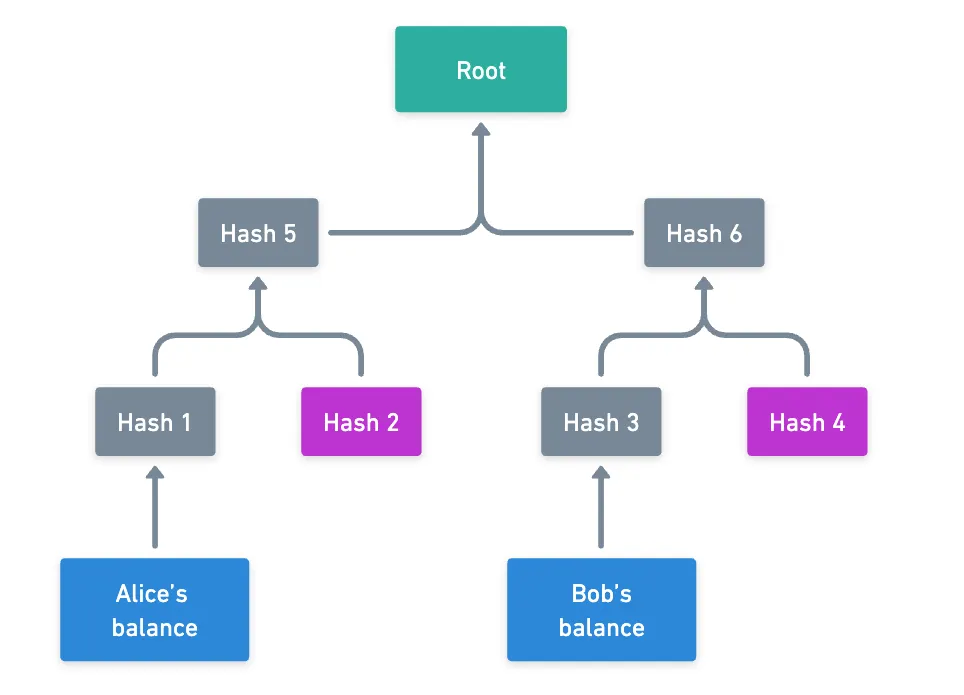

Say Alice wants to transfer some tokens to Bob. The consequence of this action is their balances being changed — but the rest of the state is pretty much untouched. Now, their balances will both represent a single leaf in the trie — something like this:

This is of course a condensed view of the full trie: the hashes in purple may hide lengthy subtries. That’s exactly the beauty of this data structure: you only need a few intermediate hashes to reconstruct the state root (which is a fingerprint of the entire trie) from Alice’s and Bob’s balances.

Granted, you normally need a few more of the purple hashes, since we’re actually working with a radix-16 trie.

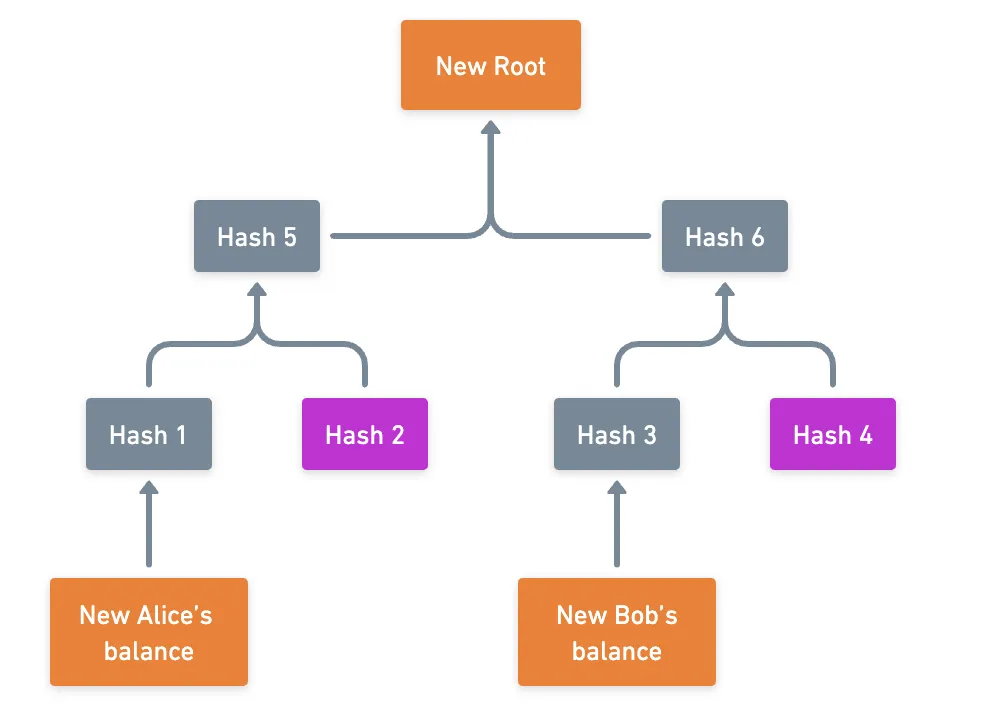

Upon changing the target balances, this is the new situation:

So having only the condensed trie from before, and the updated balances and new root, we have everything we need to verify the state transition!

To round this up, we say that these Proofs of Validity are just witness-based proofs of the state of Rollups.

With this, we’re mostly finished with the role of Collators in this story. Our next stop will be to understand how the Relay chain takes these PoVs, and validates them. Here, the challenge is to do this efficiently, since our base layer will have to work through the validation of several different Runtimes.

Rather than thinking in terms of “the Relay chain” validating these blocks, it will be useful to approach this next section in terms of individual actors, and the overall process that happens immediately after the submission of these blocks — a protocol known as ELVES.

Fun fact: the original paper states that ELVES stands for Endorsing Light Validity Evaluator System, while the official documentation establishes that it means Economic Last Validation Enforcement System.

I guess you can decide which one’s more suitable after we see it in action!

ELVES Protocol

Consensus protocols in general have but a few goals, among which are ensuring that a single shared history exists, and that each step (block) in that history is valid.

Conversely, this means that invalid blocks should never be accepted — they should be discarded after examination by Relay chain validators. But how many validators should perform this auditing? How many is safe enough?

Generally speaking, we can’t have every validator node check every single Rollup block, as that would render scaling nigh impossible.

This is a reality that most Blockchains face, and the reason why we need sophisticated consensus mechanisms.

Polkadot solves this through ELVES, which is comprised of a total of four phases or steps.

Backing

The first step is called backing.

When a Collator submits a Rollup block (along with its PoV), a small group of Relay chain validators (called backers) who are specifically assigned to that Rollup receive the block, and perform an initial validation.

Backers essentially do the heavy lifting: they execute the Rollup’s state transition function (Runtime), and verify that the PoV is correct.

If everything checks out, they attest to this via what’s called a candidate receipt, putting their seal of approval on this new block.

They back the validity of the new block, hence the name!

Availability

The second phase is called the availability phase.

Backers claim the new block is valid... But can we trust them? They could have incorrectly assessed the validity of the block, or even be lying! How can we ensure this is not the case?

Simple: have other validators do a second round of block validation.

For this, the backers need to make the block available to their peers. As easy as this sounds, there are a couple associated problems around how we distribute these blocks:

- If the backers send every block to every other peer, soon nodes would have to store lots of blocks in memory, most of which they will never check. Not ideal!

- If backers wait for challenges to come in before distributing the block, the overall latency of the process would be increased, slowing down consensus. Also not ideal.

What about an intermediate solution then? Luckily, such a thing exists in the form of a technique called erasure coding.

I’ve talked about this extensively in a previous post, so go check that out if you want a full explanation!

It goes like this: the block is divided into chunks, and only a small portion of these chunks is distributed upfront to other nodes. When a peer wants to examine the block, it can ask peers for other small chunks, and reconstruct the original block. Interestingly, they don’t need all the pieces — only a fraction will do.

This is great because communications are lean, and nodes don’t need to store that much information!

And really, the distribution happens alongside the backing phase, not purely in sequence.

Once enough validators attest to having received their respective chunks, then the protocol moves to the next phase.

Approval

Now comes the most interesting part of the protocol (in my opinion): the approvals phase, which is where the second round of revision happens.

The protocol randomly selects a small committee of validators to audit the backed blocks. Importantly, the committee is chosen after the block has been distributed in the previous phase. And the random selection is powered by Verifiable Random Functions (VRFs).

Why is this important? Because if the backers knew who would be part of the committee in advance, they could coerce them into approving the block!

By doing things in this order, we make it difficult for dishonest nodes to indulge into corrupt behaviors!

If all the committee members approve a block, then it’s accepted, and the Rollup can attach it to its chain. But some auditors may claim a block to be invalid, or they may not respond in time (called no-shows). In this scenario, another step is needed.

Escalation and Disputes

No-shows are simple to handle: ELVES selects additional random validators to provide their approvals.

This is pretty clever, actually: if the no-shows happen due to validators being attacked, then the committee keeps growing until the attacker cannot realistically keep up!

However, when an auditor claims a block to be invalid, the system goes into a dispute phase: the decision to approve a block is immediately escalated to all validators, and every single one needs to check the block and vote.

To ensure validators vote “correctly”, the protocol slashes the minority side (yes, this is a Proof of Stake protocol). We impose serious consequences for misbehavior, which adds to the security of the model. And all in all, trying to corrupt this system is quite complicated, because you’d have to:

- Corrupt the initial backing validators

- Have enough resources to crash honest auditors as they’re randomly selected

- And risk massive slashing if they’re caught!

And during “normal” operation — you know, valid blocks being produced, and nodes being available to perform their duties — only a small fraction of validators are actively checking any particular Rollup block.

In other words, this protocol is very well-suited for parallelization in the execution of the consensus mechanism!

Interoperability

Okay! We’ve covered how Rollups produce blocks ,and how the Relay chain validates them through ELVES.

We’re now only missing one last piece to Polkadot’s architecture: how do these different Rollups actually communicate with each other?

The Interoperability Challenge

We already know that most Blockchains exist in isolation.

Moving assets from one Blockchain to another Blockchain typically requires bridges — systems that simply hold your assets on one chain while minting equivalent representations on another.

Crucially, these systems are usually centralized. As such, they are frequently the weakest link in cross-chain operations. There’s a saying I’ve already mentioned when talking about cryptography:

![]()

![]() A chain is no stronger than its weakest link.

A chain is no stronger than its weakest link.![]()

![]()

And so, these bridges often become the targets of exploits.

Of course, this all stems from the simple reason that interoperability was not considered as part of the initial design of many systems, because nobody had a crystal ball.

In similar fashion to the previous article, let’s imagine for a moment we’re about to build a new Blockchain with support for native interoperability between Rollups, without relying on centralized bridges. How would that even work?

Say Alice wants to send 100 tokens stored in her account on Rollup , to Bob’s account on Rollup . This should be simple: Rollup burns Alice’s 100 tokens, and Rollup mints 100 equivalent tokens for Bob.

Piece of cake, right?

Not quite. Imagine that Rollup successfully burns the tokens, but then Rollup fails to mint them. Alice loses her tokens, and Bob gets nothing. Alternatively, if Rollup mints the tokens but Rollup fails to burn them, well... We have now essentially duplicated the tokens. Of course, both situations are alarming, and should be avoided at all costs.

To solve this, both Rollups would need to somehow coordinate a complex two-phase transaction.

Kinda like a distributed database commit.

Rollup would need to prepare to burn the tokens, Rollup would need to prepare to mint them, and only when both are ready would they actually execute the operations.

Even though this adds complexity (and latency) to the system, it’s at least theoretically possible. However, this requires some sort of mechanism for direct communication between the Rollups.

As we add more Rollups to the ecosystem, we must ensure communication between these separate systems still works. If every Rollup has its own formats and quirks, then chaos would ensue really fast.

It is almost evident that some sort of standard is needed.

Polkadot tried to learn from this, and came up with their own solution: a native cross-chain communication mechanism, in the form of XCM.

XCM

The Cross-Consensus Messaging format (or XCM for short) is simply that: a messaging format.

Although “simply” undersells its elegance. XCM is more like a universal language that describes actions. And instead of Rollups trying to coordinate complex transactions directly, XCM takes a different approach: it creates a standard way to describe intentions, which enables two things:

- it lets the Relay chain handle the coordination.

- it lets each Rollup implement the logic to handle the message.

To put this into perspective, let’s revisit the previous example. Alice wants to send 100 tokens from Rollup , to Bob’s account on Rollup . So the XCM message would say something like this:

Withdraw 100 tokens from Alice’s account, teleport them to Rollup , and deposit them into Bob’s account.

The message perfectly describes what should happen, but not how it should happen. Each Rollup interprets these instructions according to its own rules and capabilities. But that begs the question: how do we make sure that Rollup actually executes the message?

Message Execution

The answer is perhaps more nuanced than what you’d expect.

XCM follows a fire and forget model — when Rollup sends a message, it doesn’t get confirmation that Rollup executed it. But let’s take a moment to analyze a message’s lifecycle, and see what we can learn from that:

- First, Rollup crafts the XCM message and sends it “up” to the Relay chain.

- The Relay chain then stores the message in its own storage, and also routes it to a message queue in Rollup .

- When Rollup ’s Collators build their next block, they are expected to process the messages in their respective queues.

- The Relay chain validators verify that newly-produced blocks are valid, based on the processing of the received messages.

Note that this mechanism, called Horizontal Relay-routed Message Passing (HRMP), is expect to be replaced by the lighter Cross-Chain Message Passing protocol (XCMP).

The key difference is that, at present, all messages are stored in the Relay chain. XCMP aims to store messages directly on the Rollups, and keep the information stored in the Relay chain very light.

Okay, so there are a few things to say here. First and most obvious, there’s no absolute guarantee that every message will be processed by the target Rollup.

But not everything is lost — both in HRMP and XCMP, the Relay chain maintains information about what XCM messages each Rollup should execute, in the form of message queues. Thanks to this, Relay chain validators have enough context to check (and they will check) that Collators are indeed processing messages, and in the expected order. If they don’t, then their blocks will eventually not be considered valid, and their block production will be halted.

What about failed executions? Well, XCM includes mechanisms like asset trapping — assets don’t just disappear, they get trapped and can later be recovered through separate processes. Naturally, there’s more complexity around this, since XCM messages can be used to represent all sorts of actions, not just token transfers.

Overall, XCM is a step in the right direction. It has huge potential, but its success depends on how its used and implemented.

I guess we’ll have to wait and see!

Summary

We’ve covered a lot of ground today! Let’s recap real quick:

- We saw how Collators are specialized nodes that produce not only blocks, but short proofs of the validity of their state transition, in the form of Proofs of Validity.

- These blocks are then audited by the ELVES consensus protocol, which shines for it’s scalability, efficiency, and security.

- Finally, XCM enables native interoperability between rollups. It already sees a lot of use in the Polkadot ecosystem, and allows for very rich interactions.

Sure, we haven’t covered everything (for instance, I didn’t mention async backing, which is a pretty interesting feature in itself) — but this should be more than enough to have a good grasp of how consensus operates in Polkadot.

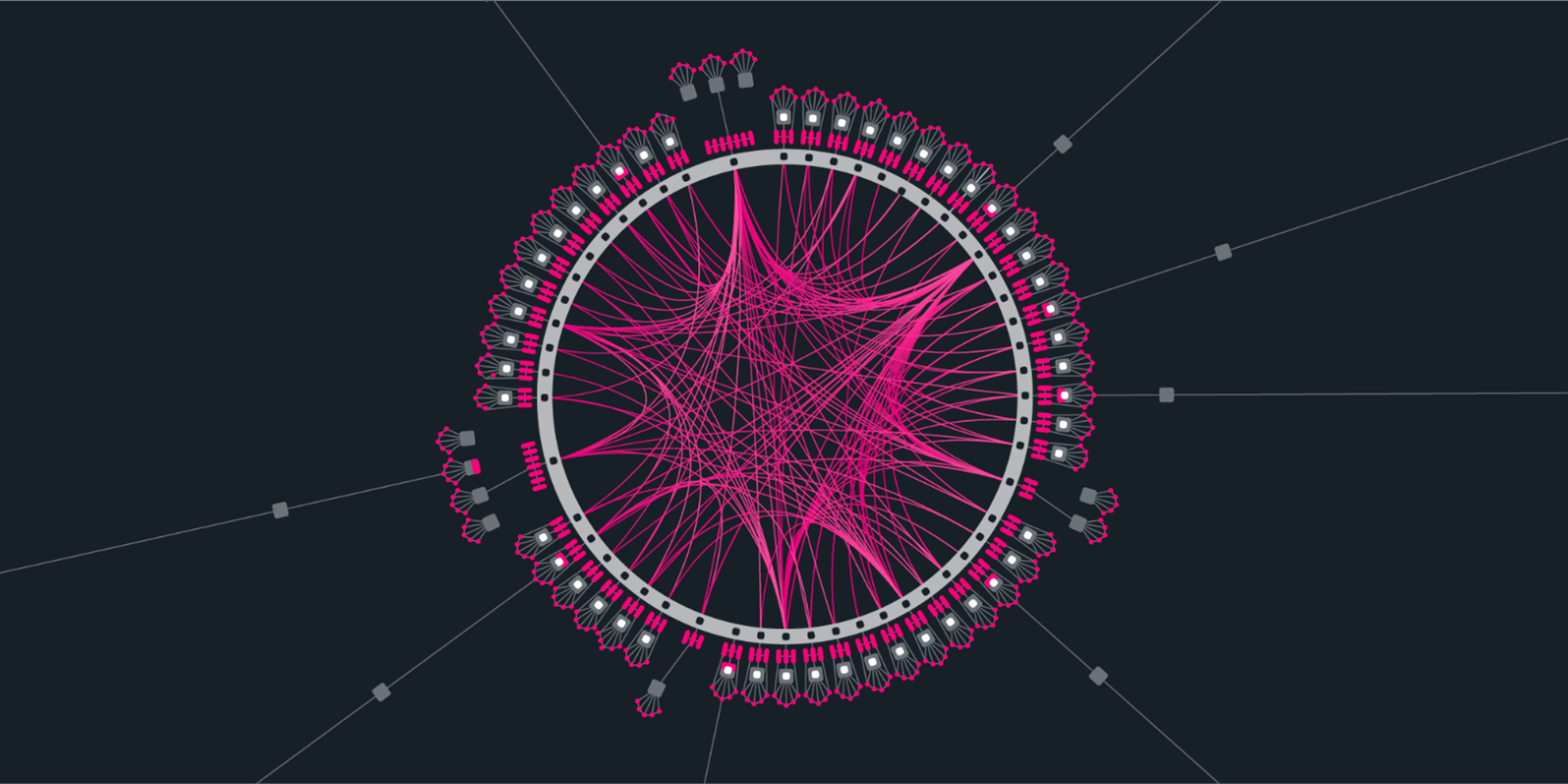

As an added bonus exercise, we can take our newfound knowledge and try to use it to understand one of those images circling around the internet about Polkadot’s architecture. Let’s see if we can identify all the components:

Each of those little things “docking” onto the circle is a group of collators (the pink dots), who produce blocks for a parachain (the grey square), and are backed by some validators (those long and rounded pink figures).

The relay chain is the big grey circle in the middle, and the pink connections threading inside of it are the XCM messages. Lastly, the “pools” of validators that seem to link to multiple collators are likely related to on-demand coretime — a concept we’ll soon explore.

What makes Polkadot pretty unique isn’t just a single innovation, but rather how these different pieces work together. It really is one of the few examples that stand out to me as an attempt to build more than just a Blockchain, but solid infrastructure for an ecosystem of interconnected Blockchains.

Of course, the other big candidate is the Ethereum ecosystem, which we shall revisit before this series ends!

Time will tell how successful this vision becomes. If anything, the amazing technical innovations we’ve discussed push the entire industry forward, and they’re definitely worth learning about.

Speaking of technical innovations, Polkadot still has a few surprises under its sleeve. For one, we haven’t answered how Rollups gain access to the validation power of the Relay chain. I mean, validators shouldn’t work for free, so there must be some sort of incentive in place, right?

I don’t want to spoil the action here, so you’ll have to wait for the next article to find the answer!

See you then!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.