WTF is Quantum Computing

This year is shaping up to be one of the big ones in the history books of quantum computing. Exciting news is hitting the headlines with the announcement of Microsoft’s Majorana 1 chip and China’s Zuchongzhi 3.0.

But what’s all the fuss about?

Because of how quantum computers operate, they are capable of solving extremely hard problems that classical computers (like the one you’re reading this on) cannot solve.

Well, actually, it’s not that they cannot do it — it’s just that they’d take a really, really long time. Imagine starting a calculation and instructing coming generations to expect the results some day in the distant future.

Sounds kinda legendary, actually.

It’s just crazy. Besides, it’s impractical.

Quantum computers are able to solve these complex problems in much more manageable times. In theory, this could revolutionize fields such as medicine, biology, engineering, and artificial intelligence, just to name a few.

However many benefits quantum computing may have, it also has a scary capability: it can break the most widely-used cryptographic methods we use on a daily basis.

It’s a double-edged sword. Whoever has access to quantum computing could potentially break our current security models, thus representing a threat on many levels.

So, how worried should we be? To answer this, I believe we must understand what quantum computing is all about, what kind of problems it can solve, and how we could rethink modern security to try and protect ourselves from this latent threat.

Vamos!

Quantum Mechanics in a Nutshell

I’m not really an expert in quantum mechanics, but I’ve had enough contact with the discipline to at least have a functional understanding.

With this modest background, all I can say is:

![]()

![]() Quantum Physics is weird

Quantum Physics is weird![]()

![]()

Keep this in mind for today’s journey. Crazy as they may seem, the ideas proposed by quantum mechanics happen to be the best description of our physical reality (at least in the realm of atoms and particles) that we’ve found so far as a species.

The most essential proposition in quantum physics is that particles don’t behave as a solid object. We may be tempted to picture them as tiny billiard balls, but that’s not how the cookie crumbles.

Not always, at least. The first documented evidence of this is the infamous double-slit experiment, which revealed that quite paradoxically, particles sometimes behave like little marbles, and other times, like waves.

What’s more, how they behave depends on whether if they are being observed or not.

I know, quite brain-melting. It’s as if the particle somehow knows it’s being watched. Of course, we could make some sense out of this – but that might be a topic we might cover another time.

Particles as Waves

Let’s not linger too much on the details, because there’s a lot to cover.

In quantum mechanics, particles are modeled as waves. This representation works like a probability distribution, in the sense that it describes what the probability of finding a particle in a certain state is.

The correct term for these “states” is observables, but we’ll go with state to make things easier to follow.

For instance, the state we’re interested in could be the particle’s position: it’s sort of a probability soup until we try to measure it. And of course, when we do, the particle has to be somewhere, so it stops living in a probabilistic world, and pops up at some position. Crazy.

This is known as collapsing the wave function, but again, let’s not focus too much on the details.

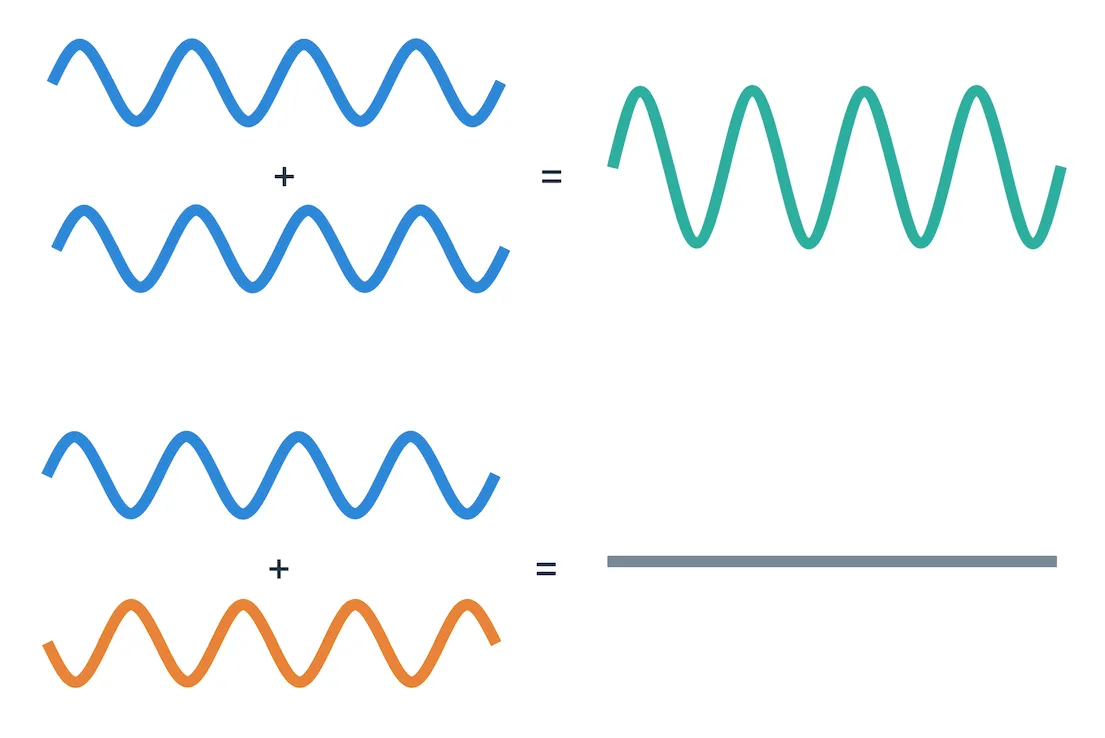

Now, waves have very interesting properties. For one, we can add waves together. The result can be constructive or destructive — adding two waves together can cancel them out completely, make the overall resulting wave even bigger, or a mix of the two.

And the cool part is we can add together any amount of waves together, even infinitely many, producing all sorts of patterns. Which leads us to the next cool concept.

Superposition

Okay, so a wave represents a possible state for a particle. What happens if we add two waves together? The particle will be in a combination of both states at the same time — a superposition, that only resolves to some value once we observe it.

Although this may sound crazy, we can tap on a more familiar example to gain some intuition: sound.

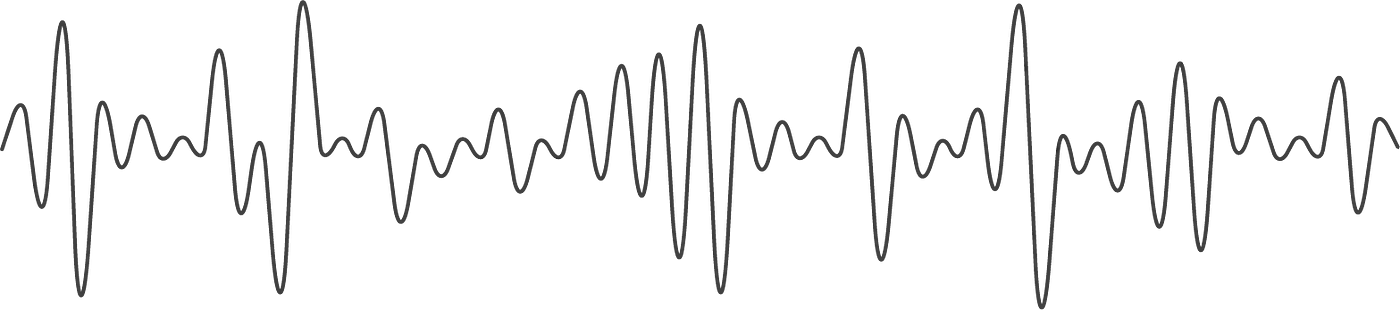

You almost never hear a “pure wave”. For reference, this is what a pure wave sounds like:

Rather, almost every single sound you hear daily is a combination of several individual waves, resulting in something messy, like this:

Yet, we’re often able to distinguish and extract information from these combinations. A conversation is a really complicated sound wave, but it means something we can perceive and decode.

But for example, if you’re in a bar and the music is really loud, and your friend is trying to tell you how wasted they are, you might not be able to understand them.

Clumping different states together works very similarly in quantum mechanics. A particle might be in a combination of states, but some of them are really loud (most probable), and overpower other ones that end up being less probable.

Good so far? Quantum mechanics is pretty weird, I know. And we haven’t covered much — just enough to understand what quantum computing is all about. I just hope you’re not like:

Take it slow. Try to wrap your head around these ideas before moving on.

Ready?

Quantum Computing Fundamentals

Alright, so we’ve briefly covered the bizarre world of quantum mechanics.

At this point, I imagine you’re wondering how the hell we get from these wave thingies into computers that can break the internet. Time to connect the dots!

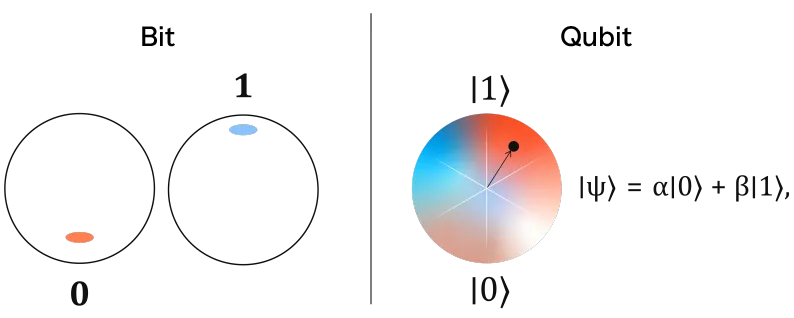

Regular computers process information using bits. You know, the familiar s and s. Each bit can only store these two values at any given time.

This might not seem like a problem at first. And to be fair, it really isn’t necessarily a problem. Modern computers can perform incredible feats using just bits — just lots of them, switching their values really, really fast.

For some applications though, this just isn’t enough. There are problems that take so freaking long to solve, that not even the combined might of all computers in the entire world could manage to solve them in a reasonable time.

Loosely speaking, if you double your computing power, you will roughly halve the time it takes to solve a problem. It’s a linear relation.

This is not generally true. It’s not that easy to parallelize problems. Let’s stick to this idea for educational purposes, but know that it’s not that simple!

And again, in some cases, you can keep doubling until you have no more computers available in the world, and you’d still be looking at a wait of a few million years.

Qubits

The story would be different if bits could hold more than a single value at a given time. We cannot achieve this without fundamentally changing how computers work — and this is where qubits come into the picture.

A qubit is similar to a bit, in the sense that its “expected” values are and . The difference is that it can hold both values at the same time.

How, you may ask? Superposition!

The state of a qubit is a combination of the “states” and .

Just think of the sound waves — sometimes you can clearly hear , others , and other times they aren’t that easy to distinguish.

Now, a single qubit is not that exciting — it sort of holds two values at once instead of one. Big deal, huh? However, when you start racking up qubits, things get spicy. Two qubits can hold four possible values at once: , , , . Use three qubits, and you get simultaneous values.

You see the trend, right? The amount of information you can hold grows exponentially with the number of qubits you use.

With just 300 qubits, you could represent more states than there are atoms in the observable universe. Mind = blown.

And of course, with 300 bits, you can represent a single state from amont possible values. Booooriiiing!

Sound promising! So how do we get a qubit?

Building a Qubit

Representing bits is really simple: it’s just current running through a circuit.

Qubits are a different kind of beast, because we need to deal with quantum systems. So when it comes to describing these systems, things get very technical really fast.

Naturally, the details are pretty involved. I just want to briefly mention some of the techniques for building qubits out there, but for now, I think it best to avoid any further descent into the wonky land of quantum mechanics.

Here they go:

- Superconducting qubits: Tiny circuits cooled to near absolute zero where electrons flow without resistance. The qubits themselves can be thought of as little hoola-hoops, whose rotation direction indicates a or a . And of course, they can sort of rotate in both directions at the same time.

- Trapped ion qubits: Actual atoms held in place by electromagnetic fields, where the electron configurations represent different states. So, quite literally, these are atoms floating in vacuum, held in place by electric fields — and the “qubit” is the atom’s electron energy level.

- Photonic qubits: Uses photons (a.k.a. light particles) to store quantum information. The “qubit” part is just a property of the photon, like its polarization — simply put, whether if it wiggles up and down, or left and right. Or a combination of both, because these are quantum systems!

Plus, there’s the topological qubits Microsoft claims to use in Majorana 1. But I still have no clue how that works.

Something to do with little cables holding quantum information, new states of matter, previously unobserved theoretical particles (the Majorana fermion)... Too much for my brain to handle, honestly.

But! There’s a catch: these systems are pretty unstable.

The slightest of disturbances can cause the carefully crafted qubits’ state to fall apart, in what’s called decoherence.

For this reason, qubits have to be extremely isolated. Like, from reality itself. This is why they are housed in giant refrigerators cooled to temperatures hundreds of times colder than outer space. And even so, the qubits only hold their states for a few microseconds, before decoherence kicks in.

So yeah, quantum computers are cool, and have tremendous potential, but they are still extremely difficult to manage.

And you will likely not be able to buy your quantum laptop any time soon!

Connecting Qubits

Alright, we have these individual qubits floating around in their super-cold isolated environments. But you cannot build a computer using only bits.

The computers we use and love work because they can combine bits using what’s called logic gates. For example, an gate takes two bits as input, and outputs if both inputs are , and otherwise. It is from these little pieces that computers are built.

Fun fact: you can build a computer using just NAND gates.

Logic gates are tiny circuits. They are really small, and have some cool physics behind them, but they are conceptually simple: if the current flows, you get a , if it doesn’t, you get a .

What about quantum computers, though? We’re gonna need to build some sort of gate in order to perform operations — we need quantum gates. But how do we do that? There are no cables connecting qubits, so how on Earth can we build gates to combine them?

Luckily, quantum mechanics still has some extra weirdness for us to leverage in order to make things work.

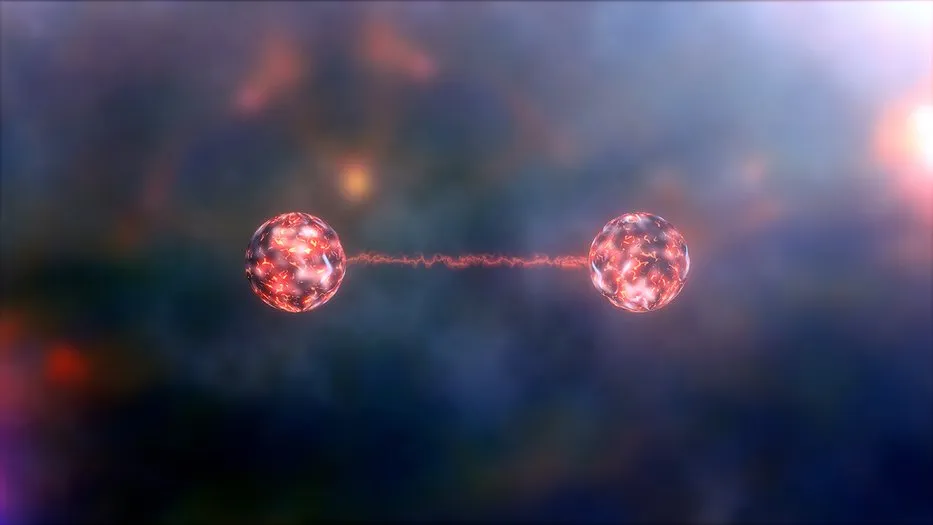

Qubits are connected through a phenomenon called entanglement.

Here’s how it works: two entangled particles have the quasi-magical property that measuring the state of one of them instantly affects the other, no matter how far apart they are in the universe. Imagine you have two entangled coins, you place them in different galaxies, and when you throw one and it comes heads, you can be absolutely sure that the other one in will show tails — every time, without fail, instantly.

It’s so weird, even the great Albert Einstein called it “spooky action at a distance”, because it seems to violate the universal limit that’s the speed of light.

Regardless, this phenomenon is the last secret ingredient that allows quantum computers to work. But there’s a catch: quantum gates don’t work exactly like your classical or gates. In fact, they’re fundamentally different.

Quantum gates are more like little transformations that change the state of a qubit or multiple qubits at once. For instance, there’s the Hadamard gate, which takes a qubit in state or and puts it into a “perfect superposition” of both.

And then, there are gates like the CNOT (Controlled-NOT) gate, which flips a target qubit depending on the state of another control qubit — entanglement in action!

Entanglement allows us to create exotic and useful types of quantum logic gates. They work differently than what we’re used to, so algorithms running on these kind of computers are also fundamentally different from the ones we build in classical computers.

Because qubits allow us to represent multiple states at once, the trick is to set up the right sequence of quantum gates so that wrong answers cancel out, while the right answers constructively interfere, and amplify each other (again, think of the sound analogy). Figuring out these sequences is an art in its own right — and that’s why routines like Shor’s algorithm are so clever and unfamiliar.

In short:

![]()

![]() The key is to harness the weirdness of quantum mechanics

The key is to harness the weirdness of quantum mechanics![]()

![]()

Summary

So, what have we learned throughout this journey?

Well, first and foremost, that quantum physics are bizarre — waves are used for state representation, systems exist in multiple states at once, entanglement... Yet, all this weirdness is exactly what makes quantum computing so powerful.

Current research is all about extending coherence time, and correcting errors when they inevitably happen. And with the recent announcements of Majorana 1 and Zuchongzhi 3.0, we may be inching closer to more stable quantum computing, whose potential can be truly exploited.

There’s one particular application that keeps security experts up at night: cryptography. Most cryptography is based on those extremely hard problems I mentioned before — some of which may be breakable in reasonable times with a sufficiently powerful quantum computer.

Not all of them though. The most sensitive ones are RSA, and algorithms based on Elliptic Curves (ECC). But things like AES are not prime targets.

Which would mean that security as we know it would be cooked.

But let’s not panic just yet. Quantum computers are still very limited — we’re still far away from the “break the internet” stage.

What’s more, cryptographers aren’t just sitting around waiting. Methods are being developed to withstand the strength of quantum computing. The area of research is called Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC).

The quantum revolution won’t happen overnight. We have time to adapt our security models. But it’s no longer an academic curiosity.

Whether that thrills or terrifies you probably depends on whether you’re more excited about revolutionary technology or more concerned about your Bitcoin wallet.

Either way, the quantum era is coming. Better get ready for it!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.