Blockchain 101: Solana Programs

This is part of a larger series of articles about Blockchain. If this is the first article you come across, I strongly recommend starting from the beginning of the series.

In the last episode, we started venturing into Solana territory, addressing how this Blockchain incorporates the concept of time into the mix, providing a simple but smart way to timestamp transactions.

But this is not the only novel idea Solana brings to the table for the purposes of this series.

You see, when we looked at Smart Contracts, a lot of effort was spent into explaining how the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) works — a set of well-defined rules that allow us to write programs.

However, not every Blockchain out there abides by these rules, and some have tried alternative approaches in search of more convenient — and hopefully better — ways to approach programmability.

One such Blockchain happens to be Solana. And today, we’ll take a look at their solution!

The Account Model

Before we get into any programmability though, we’ll need to understand a few more things about this Blockchain.

In particular, we care about how accounts are handled. Much like any EVM Blockchain, Solana also places all data associated with a single address into an account.

However, there’s a crucial difference: while EVM Blockchains bundle both code and state together in Smart Contract accounts, Solana deliberately separates executable code from program state. The first part is stored in Programs, while the second one lives in Accounts.

The obvious question to ask is why do this? What is there to gain?

It might not be obvious, but the answer is simple: it allows some degree of parallelization.

To explain what I mean by this, let’s run through a quick example.

Say you have two transactions that live on the same Program. But transaction 1 only touches a state that lives in account 1, while transaction 2 only affects a state residing in account 2. Therefore, since they are completely independent, Solana can run said transactions at the same time — in parallel!

EVM architecture doesn’t permit that out-of-the-box, because a Smart Contract and its state are tightly coupled together, and it would be very hard to determine whether two transactions are completely independent in a general setting.

We’ll get to programs in a short moment — but first, let’s zoom into what Accounts are in Solana.

Account Structure

It should not surprise us that every entity in Solana is an account — after all, the same thing happened on EVM systems (with EOAs and Contract Accounts).

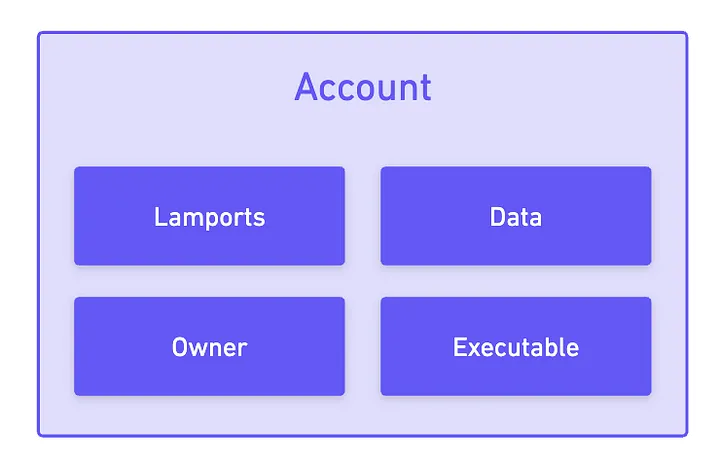

In terms of their structure, they are quite simple beasts: all we need to represent them are a few key / value pairs (again, nothing new), which are:

- Lamports: the balance of the account. One SOL is equivalent to 1.000.000.000 lamports, which is the minimum fraction of a SOL (Solana’s native token).

- Data: everything that’s stored in the account, as an array of bytes. We’ll see what lives here in just a second.

- Owner: an address that owns the account. Every single account has an owner — and it might not be who you think it is!

- Executable: whether if this account is executable or not. And yes, this will determine whether this is a Program or not.

So far, so good! We’ve been through a few battles already, so there shouldn’t be anything mysterious about these ideas — in fact, they shouldn’t feel foreign to you guys at all.

And if they are, go read the previous articles!

Okay, let’s say we want to start using Solana, so we’re gonna need our very own account!

Of course, we’ll need a keypair (aka private and public key) in order to sign transactions, and of course, the address associated with said keypair.

Solana uses the curve ed25519, which is fairly standard.

I guess you would expect that the owner of an account is the public address that controls it, right? That was my intuition, at least. Imagine my surprise when I learned I was wrong.

Yeah! All wallet accounts in Solana are owned by what’s called the System Program.

This System Program is the only program that can create accounts, and it also contains the logic to execute transactions signed by users.

It does a couple more things as well.

I know. It’s kinda weird to say you don’t own your wallet. Truth is that this only works as the single entry point for transaction processing, but in reality, all transactions must be signed — the System Program can’t change any state without said signed transactions. So you do own your account, but through your private key!

Cool! We have a wallet now. What about Programs then?

Programs

Onto the fun part!

Programs are Solana’s version of Smart Contracts. As you’d expect by all the preamble, these are simply accounts whose executable field is set to true.

And we need to store the bytecode somewhere, right? Care to guess where it will be stored?

In the data field, of course! After all, the bytecode is just a huge array of bytes.

The other question we might have at this point is who owns Program accounts. We won’t be playing any guessing games with this one, because it’s not evident at all.

Programs are created by other Programs — in particular, by a special set called Loader Programs. Or well, almost.

Accounts, as we already know, need to be created by the System Program. But then, these Loader Programs are assigned ownership of the new account, and only then do they set the data field to the Program’s bytecode.

Kinda like an installer of sorts. Oh, and it also sets the

executablefield to true!

Again, the end result is that a contract is not owned by you, the deployer. That’s fine, though — it’s simply an architectural decision of the Blockchain, and allows it to execute transactions in an organized way.

Upgradeability

If these Loader Programs can set the bytecode... Does that mean that Solana Programs are upgradeable? As in, can they have their code changed?

In short: yes! Albeit, under certain conditions: the latest Loader Programs must be used, and we can only perform upgrades if an upgrade authority is set. Programs are mutable by default, meaning that the upgrade authority is set on deploy (to the deployer’s address), and that account has permissions to change the code.

Later, the authority can be set to none, making the Program immutable.

This might sound iffy, especially after our expedition through Ethereum, where immutability is assumed. However, we can build upgradable contracts in Solidity through proxies and delegatecalls — so functionally speaking, this is nothing new.

Immutable Programs are important though: they are crucial to build trust. As users, we’d expect Programs to behave consistently, and no weirdness to happen when we move our funds — especially no malicious activity. So while it’s normal to change the code during the development stages of Programs, we’re usually expected to make them immutable when in production.

With this out of the way, let’s see how Programs actually work.

Programs in Action

Interacting with a Program involves creating a transaction, as I’m sure you were expecting. But remember — Programs and state are stored separately in Solana, which means that simply specifying which Program to call is not enough in this Blockchain.

Each Program has its own address, which we’ll use in the transaction we’re building. Moreover, we’ll also need to specify which accounts the Program should operate on — the state we want to modify.

But wait... Can any Program change any account’s state in any way it pleases? Sounds like a recipe for disaster. There must be some constraints on what Programs can do, right? Right?

Well, of course! If not, the system would be utter chaos.

And this is where the ownership system really shines: the most important restriction is just that the executing Program owns the account whose state it wants to modify.

Comparing to EVM may help cement this idea. Multiple instances of a Smart Contract can be deployed, but really, they will all share the same logic. It’s kind of inefficient to do this, since we’re occupying space in the Blockchain to store the same code over and over.

In Solana, since state is not bound to logic, we can simply reuse a program and only create new accounts for new states, effectively reusing code!

All this information is very theoretical, so I propose we look at a practical example to see if there are any other problems we may encounter.

Let’s try building a Token Program, akin to an ERC20.

Solidity provides mappings for this — but what’s the Solana equivalent for this? We only have accounts, and there are no rich data structures like mappings in sight. What do we do then?

Our goal is to keep track of how many tokens each user owns. So here’s an idea: let’s create a separate account to store each user’s balance.

But... Which accounts? I mean, we can’t just pick random addresses, can we?

Imagine that each user has to remember their account address for each token they own. That’d be terrible UX!

Ideally, we’d want to develop a system to obtain these user balance accounts, in a deterministic way, not only for initial balance assignment, but also to process transactions.

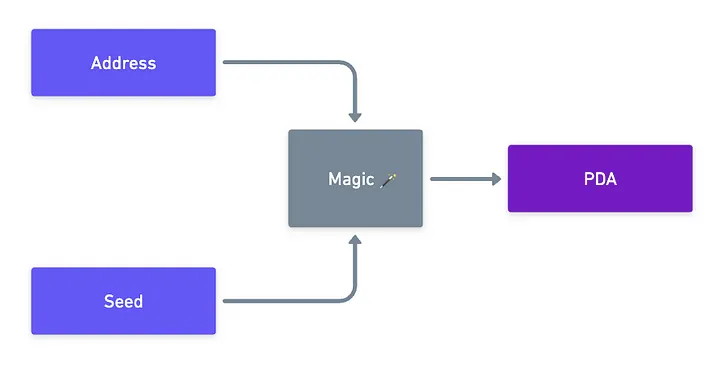

Luckily the guys at Solana also identified this problem when they were designing their system, and came up with an elegant solution: Program Derived Addresses, or PDAs for short.

Program Derived Addresses

Back when we were looking at Ethereum, we already sort of faced this problem. Mappings were just a convenient abstraction — the EVM had to do some black magic in the background to calculate where the actual data was stored.

The story’s not too different now, but it has some different flavors. A PDA is essentially a way to put some key (like a user address, a token ID, or any other value), and some other program-specific value called a seed, into a deterministic blender. Meaning that each program will know where to store data for each identifier (in our case, address), and we won’t need to remember anything — the program can figure that out for us.

The seed can be literally anything — it’s just an array of bytes!

Now, the simplest type of deterministic blender we know are hashing functions. We could go that route, yes, but these are called Program Derived Addresses, not Hashes.

Highly sus, I’d say.

And sure as hell, there’s something fancy going on.

We start off by indeed hashing our target address and seed, using Solana’s hashing function of choice, SHA-256 — the same one used for its Proof of History.

Here’s where it gets interesting: the output of SHA-256 is exactly 32 bytes, which happens to match the size of an ed25519 curve point.

Why does this matter? Because if our hash happens to lie on the curve, then that would mean that it is a valid public key.

From the mathematical perspective, you can read more about this either here or here.

And to avoid confusion, Solana addresses associated with actual private keys are just the base58-encoded public keys.

That’s no bueno — this would imply there exists some private key that can control said account. Remember, we’re trying to generate accounts to store information for a Program, who should be the sole authority over said new account. However, if there’s the possibility of somebody having control over it, then this would undermine all of Solana’s execution guarantees!

To mitigate this, PDAs use a clever trick. During generation, if the hash happens to be a valid curve point, then it’s discarded, and the process starts again by adding a small bump. This bump works essentially like salts or nonces do — and it will help produce an entirely different hash. We repeat this process until we get a hash that’s not a valid point on the curve — and there you go! A valid address, with no private key.

The last piece of the puzzle is that this bump is obtained from a sequence of integers, ranging from to . As a consequence, it doesn’t need to be stored anywhere — every time a PDA needs to be calculated, the same deterministic process can be executed, and stop at the first valid bump.

Still, I think the bump is cached locally for efficiency sometimes.

And there you have it! Hashmap-like structures in Solana, using nothing but its native elements! Isn’t that neat?

Summary

Naturally, there’s much more to say about the Solana ecosystem.

My goal isn’t to cover every single detail about each protocol — otherwise, I couldn’t possibly ever finish this series!

If you’re interested in going deeper, some topics worth exploring include Cross-Program Invocation (how programs call other programs), the Solana runtime’s transaction processing pipeline, the various native programs that provide core blockchain functionality, or cool features like support for partial signatures and fee sponsoring.

Nevertheless, we’ve covered quite a lot of ground in these past two articles. I believe we’ve touched upon the two most critical developments Solana brings to the table: its Proof of History, and now its account model, which marks our first departure from the EVM model.

Sometimes, this account architecture and all the surrounding suite of programs is called the Solana Virtual Machine, or SVM. I think the term did not hit as hard as EVM did, but still, it does reflect the completely different architecture.

Perhaps because it matches the initials of the well-established technique of Support Vector Machines? Who knows.

And we saw some of its advantages: allowing some native parallel execution when a program interacts with independent states, stored in independent accounts. This is key, as parallelization is an important feature for scalability. We’ll get to that soon.

All in all, Solana introduces some interesting ideas, that keep nurturing us in our Blockchain journey.

Although we’ll be leaving this ecosystem for now, I encourage you to keep doing some research, as this is one of the biggest Blockchains out there — so it’s definitely worth keeping an eye on!

Speaking of new ideas, I want to dedicate the next article to briefly looking at some other players in the industry that have pioneered new concepts, in search for improvements to this ever-developing world of Blockchain.

I’ll see you soon!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.