Blockchain 101: JAM

This is part of a larger series of articles about Blockchain. If this is the first article you come across, I strongly recommend starting from the beginning of the series.

The previous three articles (intro, consensus, and Coretime) are more than enough to understand Polkadot at a high level. Granted: there’s always more to cover, and it would be hard-pressed to expect becoming an expert over just three articles.

This is pretty much true for every Blockchain we’ve presented: in their majority, they have vibrant ecosystems around them, and simply too many details to go over. It’s simply impossible to condense all that in this short series!

Still, we could stop here, and it would probably be just fine.

However, the Polkadot scene was shaken by some interesting news not that long ago. Gavin Wood (the guy behind Polkadot) went ahead and dropped a huge bomb on the future of the network, and proceeded to reveal his latest brainchild: the Join-Accumulate Machine (or simply JAM).

Here’s a presentation by the man himself explaining what this is about:

I know — these kinds of explanations in isolation can feel a bit daunting, or at the very least a bit mind-bending.

As such, JAM has sparked equal amounts of interest and confusion. I remember a few peers being super excited by the news, talking about it in group chats — but when asked about the topic, they just... Didn’t seem to know how to explain anything about it other than “yeah, it’s what’s coming next in Polkadot”.

You can find and read the graypaper yourself, but it’s honestly pretty lengthy, and not particularly light.

To be honest, that felt somewhat discouraging, and I just didn’t try too hard to wrap my head around these new ideas at that time.

Now that I’m writing about Polkadot, I realize JAM truly feels like a natural evolution. If you recall, we left off the previous article questioning whether we could repurpose Polkadot’s consensus algorithm to validate any computation — not just the state transition functions of Rollups. Spoiler: JAM is indeed an attempt at generalizing decentralized computation.

My goal for today is to try and help clarify what this is all about, and focus on the core elements that define the technology. After reading this, I hope it’s abundantly clear why this is a very promising development in the lifecycle of Polkadot.

I’m not the first one to try this though. I also recommend this talk by Kian Paimani, one of the engineers currently implementing JAM. He was also one of my teachers back at the Academy!

Alright, enough chatter. Buckle up, and let’s get started!

Dissecting Polkadot

Let’s briefly recap, shall we?

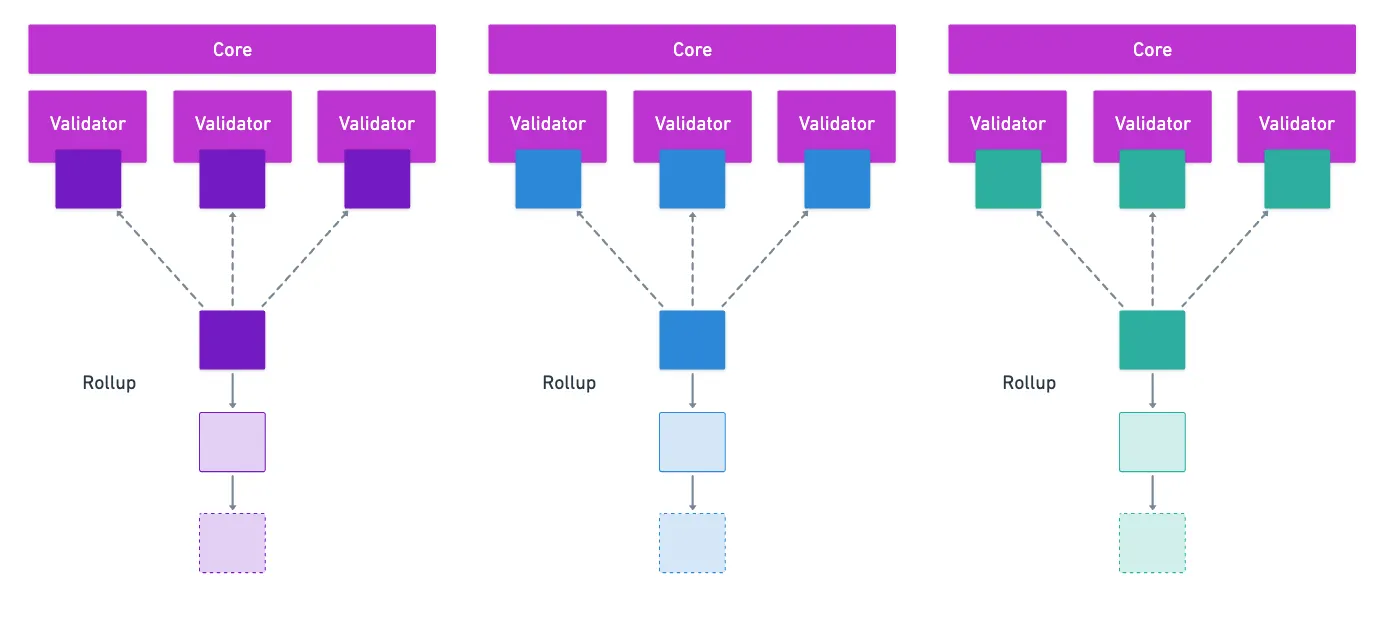

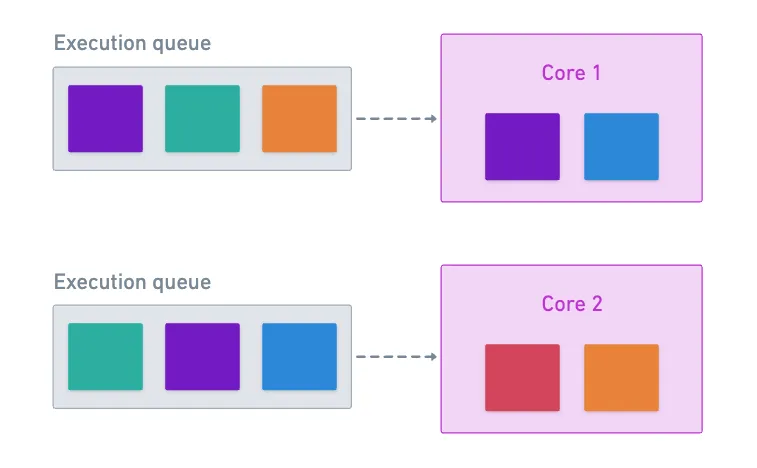

Through ELVES, the Relay Chain assigns groups of validators to check on the state transition functions of each Rollup. And we mentioned in the previous article that each group of validators essentially works as a core — something like a CPU, running computation in the form of the execution of a Rollup state transition function, with a block as input.

Yeah, it’s a mouthful — but it sums up what we’ve seen so far quite nicely.

Essentially, what we have is a way to separate the group of all validators for the Relay Chain into smaller sets that can perform computation in parallel. This is commonly referred to as sharding — and it’s a very sought-after feature in Blockchain design.

What Polkadot has essentially achieved is a fully functional sharding strategy, and that’s quite remarkable on its own. But if we zoom in a bit closer, what we have is just a distributed computer, that only ever executes Rollup blocks.

That’s how Polkadot is wired. But ELVES and Agile Coretime together could in theory run any code — cores (remember, groups of validators) would receive execution instructions, along with possibly some data, and they’d just do their job.

JAM is simply the realization of this idea. Rollups would just be a type of program that could run on this distributed computer. The whole gist of the matter is to generalize what the network currently offers, opening up possibilities beyond what we’re used to (you know, Rollups and stuff).

When put like this, it doesn’t sound so scary, doesn’t it?

Of course, this simple overview won’t cut it. We’re gonna need to be a little more precise for this to truly come together.

Redesigning Execution

Okay. If we no longer want to limit ourselves to Rollups and Runtimes, then we’re going to need to define just what comprises a computation, and how it should operate in this new setting.

Again, it’s instructive to look at the journey of a standard Rollup block. In previous articles, we’ve seen that three key things happen:

- The block is processed by a core,

- Information for the resulting state is distributed in the form of Reed-Solomon codewords (data availability),

- And some form of attestation is permanently embedded into the Relay Chain’s state.

Data availability guarantees that execution can be verified, while the attestation is sort of a seal of approval that some computation has been executed — it just so happens that this computation is the processing of a block!

And as previously mentioned, we could in principle do the same process with any computation. Which leads us to our first JAM concept: Services.

Services

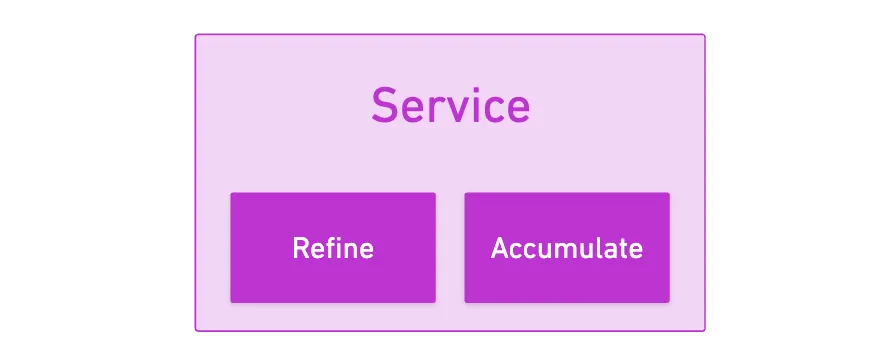

A Service is really nothing more than a program — alas, one with a certain structure and properties.

What this program needs to define are just two functions or entry points that will let us use all this JAM machinery: refine and accumulate.

There used to be a third function, on transfer, which would execute after accumulate — but it was removed in version 0.7.1 of the graypaper (thanks to my good friend Francisco for the specific detail).

Furthermore, these Services can receive work items or work packages, which are in essence requests for execution of the static Service code, defined in those two functions mentioned above.

Perhaps a good analogy would be to equate Services to Smart Contracts, and work items to transactions. Another possible comparison would be that of Rollup Runtime (Service), and its blocks (work package).You can probably start noticing the similarities, and how it feels like a true generalization!

But... What the heck are those function names? Refine? Accumulate? What?

I don’t know about you, but they don’t ring much of a bell to me without context. Sure, we could try to make sense out of them in the context of JAM — but I feel it’s gonna be much more instructive to zoom out for a moment, and focus on what we’re trying to achieve here: to build a decentralized computer that can process work in parallel.

A Multi-Core Computer

Did you know most modern computers have multiple CPU cores inside?

Yup. And when you want to execute tasks on your machine, you’ll want to follow certain practical rules. First, independent tasks could run on different cores, so that you don’t have to wait until one ends to start the next one. Parallelization is natural when tasks are completely disjoint from one another.

Secondly, if you have some heavy-duty task, executing it on a single core may not make the best use of resources, so you’ll probably want to split the task, and execute it on multiple cores. You’ll be executing these pieces of the original task in parallel.

There’s no free lunch, though — the separation comes at a cost. Namely, because the new processes are most likely not fully independent, you’ll need an extra step at the end to aggregate or integrate the results, combining them to obtain the final result of the parallelized computation.

Hint, hint!

If you’ll incur in an extra step to aggregate the results, then it makes sense to try and make the best use of each in-core computation. For that, you’ll want to give the core all the information it needs to perform whatever task it runs. This way, we avoid spending resources on writing to permanent memory, allowing the core to focus on performing the actual computation. Whatever output we get, we just push it out to some shared memory location.

In other words, we want the core to be stateless.

Lastly, if the integration step needs any more work to be done in order to complete a task, it will simply queue up whatever computations come next — until there’s no more work to be done, and the overall process is finished.

Pretty straightforward, right? Of course, this does come with some complications, such as how to separate tasks to run in parallel. But other than that, there’s no mystery in all of this.

JAM replicates this model, but in a distributed manner. The analogy is quite straightforward:

- Cores are groups of validators that process work items in parallel, one cycle at a time. Raw input data gets refined into a useful output!

- The shared memory is substituted by a data availability layer that acts as shared storage that all cores can read from.

- The integration of results is performed in the accumulate step: results of computations in individual cores are gathered as they become available.

And there you go! Pretty elegant, right?

Now let’s see how this all plays out in practice during a JAM cycle.

Step by Step JAM

The consensus algorithm, ELVES, runs in cycles. This, we already know. Therefore, what we’re about to describe is a single cycle!

When a core receives a work package for a Service, the first thing it does is run what’s called an authorizer. It’s nothing more than the core asking: can this work be executed? The conditions to be checked here may vary — for instance, we might want to check that the corresponding Coretime has been paid for.

Once a work package is authorized, the next thing the cycle does is call the refine function — remember, this is where the raw data gets processed. Work packages are bundles of work items, and the latter are what really gets executed.

Think of it as being an overarching program, and its individual steps.

This refine activity, as we previously mentioned, is stateless. Data goes in, some computations are performed, data is spit out, and that’s it.

Next up, the output from refine needs to be made available to the rest of the network. Data gets encoded into Reed-Solomon codewords, and distributed across validators for data availability.

I’ve already discussed erasure coding in previous articles. It’s quite interesting on its own, so I recommend giving it a read if you haven’t already!

And lastly, work items processed in parallel get consolidated in the accumulate phase, where validators read results from this shared data layer, and verify what work has been finished.

To drive the concept home, we need to note that each core will have a list of tasks it needs to execute. Suppose we want to execute two tasks in parallel; nothing guarantees that two cores will process it at the same time.

Each core simply picks up the next work package from its queue when it’s ready. Allowing this to happen means that the accumulate step will have to wait before it can deem the blue task as finished.

So yes, it allows for accumulation of partial results to happen in the data availability layer!

This simple design keeps the system flexible and efficient, allowing it to both scale and be more general than other traditional Blockchain systems.

Examples

To showcase what can be done with JAM, I want to present some ideas of things you could do to harness the power of the decentralized parallel computation.

Let’s get crazy!

- Decentralized oracle network: imagine a Service that processes and aggregates price data that’s been submitted to the network. Work items would contain price data submitted by oracle providers, and different cores would process and validate these submissions. Accumulate would for example compute a weighted average price, perhaps filtering out invalid submissions or outliers.

- Fraud detection system: we could analyze transaction patterns to detect suspicious activity. Work items would contain batches of recent transactions, and cores would run different detection algorithms in parallel — one checking for unusual spending patterns, another analyzing transaction timing, and yet another one evaluating if some wallet is on some known blacklists. Accumulate would combine all the analysis results to generate a comprehensive risk score for each transaction. If certain thresholds are exceeded, we could trigger alerts or additional verification processes.

- Heavy-duty computation: we want to run a protein folding simulation, which needs massive parallel processing. Each work item might simulate a small portion of the protein structure, and hundreds of cores could work on different parts simultaneously. Partial results would then get combined during accumulate to build the complete folded structure. And if more iterations are needed, they can be easily triggered.

We could even think of more extreme examples, like running a large language model on JAM!

I’m not saying any of these examples are necessarily practical — only that they are possible!

With that, we’ve covered two of the most crucial aspects of JAM: what it is (a generalized model for decentralized computation), and how it works (with its parallel processing model).

However, if you’ve been paying close attention, you may have noticed that something critical is missing: what exactly is the code we should be writing? And how do cores execute it?

The PVM

By this point, we know not to be surprised by such question. Blockchains resort to the idea of virtual machines for this: Ethereum has EVM, Solana has SVM, and Polkadot originally had WebAssembly (WASM).

The idea is simple: we want all validators to run the same code under the same conditions, so their particular hardware cannot play a role in all this, because otherwise we’d be compromising determinism.Determinism is critical for consensus: how could nodes ever come to agreement, if they could potentially get different results for the same computation?

The JAM specification also introduces the Polkadot Virtual Machine (PVM) as its execution environment. It’s pretty much the engine that actually runs Service code when cores execute refine and accumulate.

Why the move away from WebAssembly, you may ask? Well, there’s a plethora of reasons. Concretely, WASM had a few inherent problems that needed addressing from the moment it was chosen as the backbone for Polkadot’s logic.

Let’s mention a couple — and while we do so, we’ll say a few things about the PVM.

Determinism

Again?

Yeah — we mentioned determinism just a few paragraphs ago. Turns out it’s sort of a problem in WASM: it has some non-deterministic code baked into the specification. Things like floating-point numeric representation by default.

This is not necessarily a bad feature — it’s just that when dealing with Blockchains, it’s potentially really harmful. There are a few tricks we can use to avoid these potential pitfalls, but they add complexity, and much unneeded extra computation.

In contrast, PVM is a RISC-V-based virtual machine.

I’ve talked about RISC-V briefly in a recent article! Note that it’s RISC-V-based, but it’s not exactly RISC-V.

What this means is that the instruction set architecture (think opcodes) is tailored for the operations you’d want to run in an environment designed specifically for Blockchain. Or put differently, you completely disallow all unneeded behaviors (such as floating point operations). Thus, you get much tighter control over execution behavior, while keeping things lean and performant.

Metering

Another big problem with WASM has to do with the estimation of the costs to execute different instructions.

Since we want to charge for network usage, it’s important to have precise mechanisms to measure usage. In turn, this confers the network the property of being predictable — you can estimate how much computation you’ll require to finish a certain task, and with that, you can estimate costs.

Models like EVM are clearly metered — and metering is embodied in the form of gas.

WASM doesn’t fare too well in this territory. It was designed with generality in mind: sort of a “compile once, run anywhere” philosophy. Therefore, the code might be mapped to a set of very different instructions in different machines. Meaning that how things actually get executed depend on the hardware. And we know that’s no bueno.

Again, there are some tricks to try and get some predictability in fees, but they felt like patches to try and fix a problem that lived at the architecture level.

If you haven’t had to do benchmarking in the Polkadot SDK... You don’t know how lucky you are. Oh boy, that was true suffering.

The PVM allows easy metering by design. Sure, the RISC-V-like instructions have to compile to machine code at some point (like with any virtual machine), but we can measure execution effort in terms of the instructions of the PVM itself.

Much like EVM!

Being designed from the ground up, the PVM was designed to circumvent these shortcomings. From a developer’s perspective, you won’t notice much of a difference — you can still write Services in Rust or C, and they compile to RISC-V-like instructions instead of WASM bytecode.

What matters is that under the hood, JAM gets the deterministic, efficient execution it needs for its parallel processing model.

While I don’t want to dive into the full specification of the PVM, there’s one particular feature that’s quite novel, and really worth highlighting: the ability to pause a computation.

Pause & Resume

Following up our analogy with computers from earlier, we could examine how programs are executed.

At its core (no pun intended), programs are just sets of instructions that run one at a time. As they get executed, these instructions prompt the system to store information in memory, building an execution context. The programs themselves are static groups of instructions, but the particular context (or particular state of the computation) will vary.

There are in fact several models for computation that help us understand why pause and resume is even possible in the first place. In particular, the PVM is modeled as a register machine, which might feel familiar because it’s closer to the computers we use on a daily basis.Actually, there’s a whole field of study called computational complexity theory which examines different abstract machines and their capabilities (among other things).

So, if we stop any process in its tracks, what do we get? Let’s see:

- The current instruction being executed.

- A bunch of information in memory (registers, and RAM).

Nothing more, nothing less!

If we pause execution, grab this state mentioned above, and provide it to another core along with the full code to execute, then it should be able to continue executing the program as if nothing had happened.

This sounds silly, but actually, most Blockchain VMs are simply not able to do this. Computations are performed until you run out of gas, and there’s just no native way to continue with computation on the next block.

Nothing was unintentional about that design decision: not only do blocks have a fixed amount of space, but systems also work with transactions, which are intended to be block-contained to keep the overall state coherent.

PVM fully ignores this restriction. If you want to restrict computations to a single block, fine! Let nothing stop you, champ. But what about some long-running task that could never fit in a single block? You just accumulate and continue!

This pairs excellently with how computation gets charged for: you don’t pay for gas, you pay for Coretime!

It would be fine to dive into the internals of the PVM design — but I believe we’ve gone through enough stuff for a single post.

So it will be a story for another time!

Summary

With this, we’ve reached the very vanguard of Polkadot’s design. We went deep enough to start getting acquainted with the fundamental concepts, but also not too shallow to miss the mark on what JAM actually entails.

If you think about it, this is a beautiful consolidation of the previous three articles: how things started with generality as a goal, how consensus was designed with sharding in mind, how an entirely different model was crafted to pay for computation, and lastly, this: how everything comes together as a true decentralized computer, rather than only a decentralized ledger technology.

As a corollary:

![]()

![]() JAM isn’t just an incremental upgrade — it’s a fundamental redesign of what Blockchain can be.

JAM isn’t just an incremental upgrade — it’s a fundamental redesign of what Blockchain can be.![]()

![]()

It’s a super ambitious idea, for sure.

However, one can’t help but wonder about adoption. There’s no doubt that JAM is a great feat of engineering — but will it be used? Will it live up to the hype? Can it be the next killer Blockchain, or will nobody care about decentralized parallel computation?

Only time will tell. Teams around the world are rushing to create functional JAM implementations, so we’ll have to wait a little until we see this entire story unfold.

And honestly, it’s pretty exciting!

With Polkadot behind us, one would think that there’s not much less to cover — and indeed, we’re inching closer to the end of the series.

But there are some quirks that we haven’t yet talked about, one of which is a modern buzzword: ZK proofs. They are slowly making their way into the Blockchain space, and in the next article, I want to explore how they may impact the future of this technology.

I’ll see you soon!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.