Blockchain 101: Beyond The Blockchain (Part 2)

This is part of a larger series of articles about Blockchain. If this is the first article you come across, I strongly recommend starting from the beginning of the series.

Last time around, we drifted off the beaten path, and talked about Hedera, a network whose fundamental data structure for consensus is not a Blockchain, but a Hashgraph.

Really, Hashgraph is just a fancy word for a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), which is a well-known and very useful type of graph.

But Hedera’s approach is also disruptive in the sense that it discards the idea of blocks, in favor of events. So I guess we could ask ourselves if a middle point could exist: preserving blocks, but using a DAG instead of a Blockchain.

Well, technically, a Blockchain IS a DAG, where each node has exactly one ancestor. I guess it would be more semantically accurate to compare it with a linked list, though. A hash linked list, perhaps?

Fun fact, this was actually one of the first questions I asked myself when learning about Blockchain systems. Shortly after though, I understood that this was a very difficult technical feat for a couple strong reasons, so I stopped pursuing the idea at that time.

Fast forward a few years, and it turns out people are really trying the DAG concept — but maybe not in the way I had imagined.

So today, I want to show you one such approach that uses a DAG with blocks as nodes (a BlockDAG, if you will), and how they use this to evolve an old friend of ours: Proof of Work.

Buckle up, and let’s jump straight into the action!

Forks

Let’s start in pretty much the same vein as in the last article: going back to the very basics.

We’ve talked about forks extensively throughout this series, but right now, I want us to revisit them from a slightly different angle.

In Proof of Work, when two miners find a valid block at roughly the same time, the network temporarily splits into two competing chains. Both blocks are perfectly valid, as they contain legitimate transactions, and represent honest computational work. But eventually, one chain will grow longer, causing the other (shorter) chain to be abandoned by the network.

That’s wasteful. All that computational effort put into the discarded blocks? Gone.

Yup. And although the transactions will eventually make it into another block, we can’t help to think that there might be another way — one which avoids having to throw away all that valuable effort.

This is part of the reason why other consensus mechanisms emerged as an attempt to create more efficient algorithms, among other things.

Such alternatives do exist. There’s a different stance we could take in the face of the inefficiencies of traditional Proof of Work. What if we don’t throw away any blocks? What if we could harness all the information contained in them?

Challenges

Of course, this is no simple task.

It’s important to consider why traditional Proof of Work chooses to discard shorter competing chains. And there’s very good reason for that.

If we design a system such that it preserves these branching forks, then we’ll face several problems, namely:

- How do we handle conflicting transactions across different branches?

- How do we prevent double-spending when the same transaction could appear in multiple blocks?

- How do we maintain a consistent state when we accepting multiple “truths” simultaneously?

- But most importantly, how do we order transactions when they’re spread across branches?

Satoshi’s choice of having a single winning chain simply avoids all these complications. It’s a clean and deterministic solution — but at the cost of incredible amounts of wasted computation.

Technology has evolved a lot since, though. And the guys at Kaspa set out to preserve blocks, and solve all those challenges in the meantime.

Meet Kaspa

Kaspa is a relatively young Blockchain, with only nearly 4 years of age at the time of writing this article. But don’t let its age fool you — it’s built on some seriously sophisticated ideas.

Like Bitcoin, it uses the both UTXO model and Proof of Work consensus, so we’re in familiar terrain here.

But unlike Bitcoin, which produces one block every 10 minutes, Kaspa cranks out one block per second. Yes, you read that right — one block per second, using Proof of Work.

With the latest updates, I think it’s even more than one block per second, actually.

And yeah, I know what you’re thinking. It feels weird. The entire gist of Proof of Work is that finding a new block takes time and effort. So it’s natural to ask ourselves how on Earth this doesn’t end up being complete chaos.

The GHOSTDAG Protocol

In order to make things work, the folks at Kaspa came up with a consensus algorithm they dubbed the GHOSTDAG protocol.

GHOST stands for Greedy Heaviest Observed Sub-Tree. I don’t think it’s necessarily easy to make out what this is about just by that acronym. So to clarify, it’s essentially a way to give preference mechanisms for fork selection, by choosing the “heavier one”, usually in terms of computational work. This should sound familiar!

And DAG, well... You already know what that means!

To give you a rough idea before we get into the details, what happens is that every single valid block is preserved, but blocks are not considered equal when it comes to transaction ordering. That’s really the secret sauce in a nutshell.

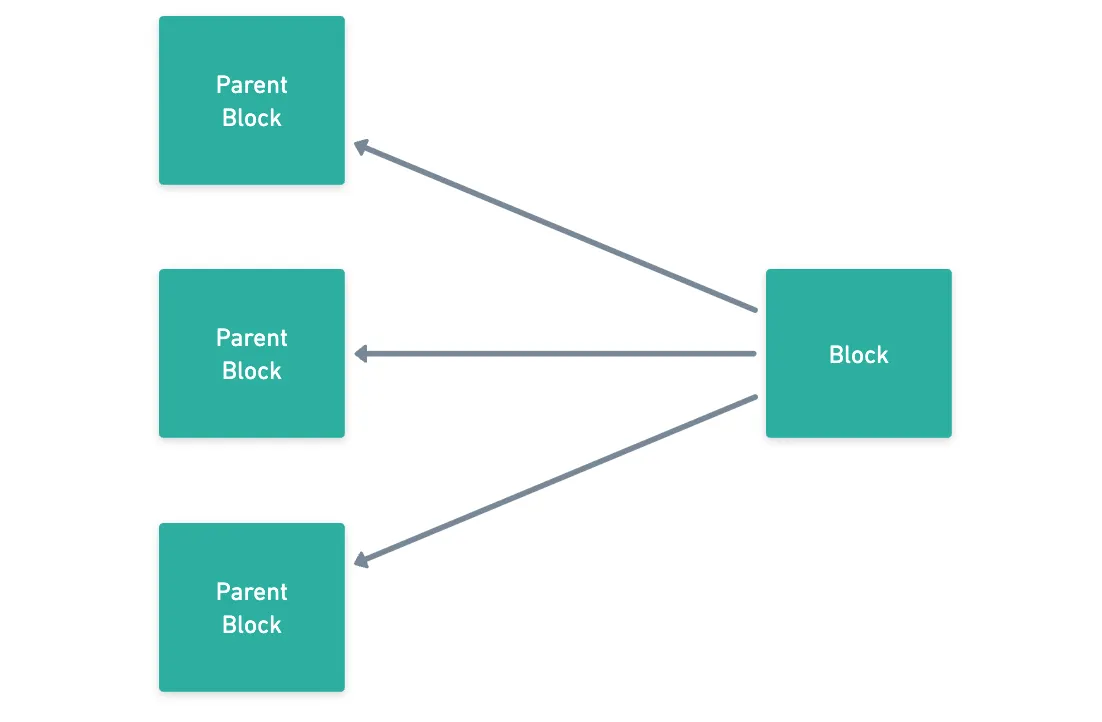

But how does this work, though? First off, blocks in Kaspa can reference multiple parent blocks.

This of course results in a web-like structure, that ends up being our DAG. And as you can imagine, this doesn’t really achieve anything on its own, other than creating a bigger mess than usual.

However, things start making sense once we apply the GHOST rule. This is at the very heart of the matter, so let’s piece it apart step by step.

GHOST

We now have a DAG full of blocks, and what we need is a way to determine which transactions actually get executed, and in what order. And we can’t just execute everything — that would lead to conflicts, double-spending, and all sorts of problems. Not exactly the type of system we’re interested in.

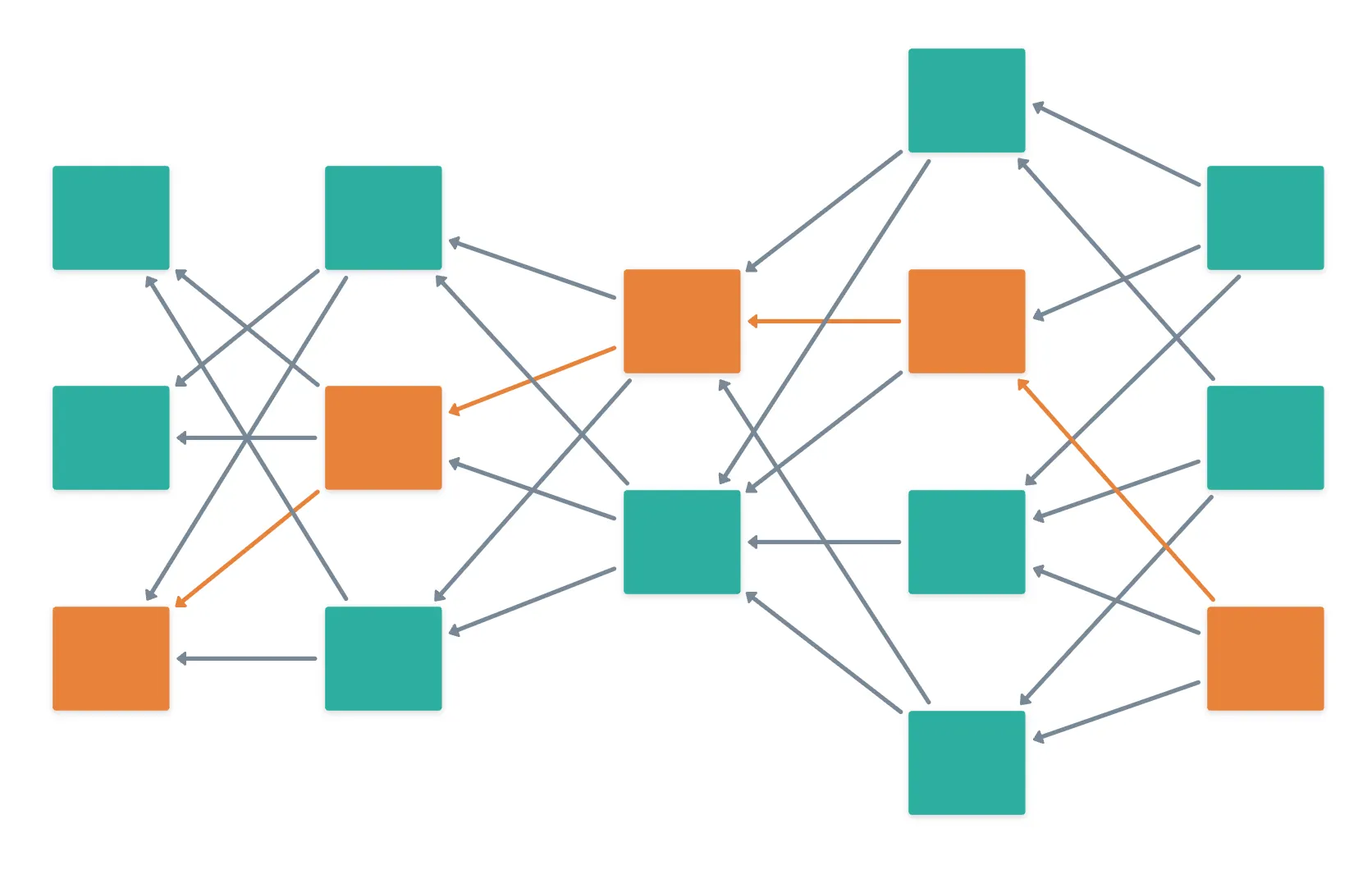

GHOST solves this by introducing the concept of a selected chain, which is a linear subgraph (so a chain) within the DAG.

Think of it as finding the main highway in a highly complex network of roads.

Let’s say we possess the current state of the network, in the form of a giant DAG. To determine the selected chain, we’d follow these steps:

- Start from a block at the tip (or end) of the DAG. In other words, one of the very latest blocks.

- Then, traverse the DAG backwards through all the possible paths determined by parent references, until you reach the Genesis block (the very first block!).

- Calculate the total weight of said paths, and choose the heaviest one.

- The tip of the DAG that has the heaviest subDAG will be part of the selected chain.

Okay, that was surely a mouthful. And as described, pretty much infeasible. So let’s unpack a bit, shall we?

Block Weight

First, what should we understand by heaviest subDAG? How do we measure accumulated work? And in that same line, how do we measure the work spent in a single block?

We already know that mining a block is about finding some nonce that produces a block hash that meets some special condition. For instance, we could require that the first 6 digits of the binary representation of the hash are ones, like this:

![]()

![]() 1111110000000010011110010000110001101010011000010100101110100011001101001101000110101101010010100001100000110101001101110011011111100100110010100110011010011100100111100101100110100000100000101100001101010011001100010000110110100000101010011100100010010010

1111110000000010011110010000110001101010011000010100101110100011001101001101000110101101010010100001100000110101001101110011011111100100110010100110011010011100100111100101100110100000100000101100001101010011001100010000110110100000101010011100100010010010![]()

![]()

Fun fact: that’s the SHA-256 of the string “Kaspa GHOSTDAG consensus mechanism”. I had to fiddle around with inputs for a while — a testament to this being a non-trivial problem to solve!

Normally though, what we do is interpret the hash as a positive integer, and simply check that its value is below some threshold. This is very simple to check, and in fact, this threshold has a name: it’s called the difficulty target of blocks.

The lower the difficulty target, the more work you need to put in to find a valid block. Which, in other words, means that these values are inversely proportional.

Cool — we now have a way to measure work. What’s next?

SubDAG Weight

As previously outlined, the next step involves calculating the accumulated weight of subDAGs, for all the tips of the DAG.

The reason why we do this is because we still need a single source of truth: we need to derive a history of events from our DAG that makes sense, and that avoids conflicts and double-spending.

We do this is by sort of assigning a score to each possible chain, and the metric we use is accumulated weight, which is just the sum of the individual weights of blocks in a single subDAG (or path, to be more precise).

If you want a more mathematical perspective, what we’re doing is deriving a topological ordering of the set of all possible subDAGs associated with the tips, which allows us to select the supremum of the topology.

Or in plain english: we have a total ordering of blocks, based on accumulated weight!

When putting it all together, the consequence ends up being the same one as in traditional Proof of Work: the chain with the most work still wins. However, in this case every single block can contribute to weight calculation. In this sense, we could say that no work is truly wasted.

And that’s pretty much the bulk of it! We have obtained a deterministic way to determine the selected chain, and this one will be the one we interpret as the history of events in the network.

It’s important that we stop here, and focus on a small detail. If we had to do this subDAG calculation for every single new block, this would simply become an infeasible process, due to the sheer scale of the growing DAG.So it’s absolutely necessary that the algorithm caches the weights of paths leading to the Genesis. This is key for the success of the strategy!

I guess there’s one little remaining piece to solve: what happens to all those transactions in the non-selected blocks? Could we use them somehow?

Non-Selected Blocks

Remember, we’re not throwing away these blocks — they’re perfectly valid work, still part of the DAG, and contribute to the overall security.

And here, GHOSTDAG does something really clever: it processes all transactions in non-selected blocks as well, as long as they don’t conflict with the ones in the selected path!

In fact, it goes even further than that: if two transactions conflict between two non-selected blocks, it just processes the transaction from whichever block comes first in the total ordering. Because remember — we have a way to order blocks by their accumulated work.

Essentially, we have a way to order every single block in the DAG!

This way, every miner can get a reward for their work, and most of their transactions still get to included in the overall history.

Furthermore, if we assume that most blocks at the same height will have non-conflicting transactions (similar to the Aptos approach), then something beautiful happens: most transactions in mined blocks can be processed!

And only in the extreme scenario that every single transaction in non-selected blocks conflicts with the selected chain, we’d effectively be executing only the blocks in the selected chain — so it falls back to the behavior of a Blockchain.

How cool is that?

Summary

I don’t know about you, but I find this truly sensational.

By moving away from the Blockchain structure, we can seemingly get the best out of Proof of Work. GHOSTDAG really has some cool benefits, such as:

- No work is wasted, and every valid block contributes to both the security and the history of the network,

- Transactions are clearly ordered, all the time,

- And massive throughput, because multiple blocks can be processed simultaneously.

All this by following the same old principle: the chain with the most work still wins.

But with a twist!

So there you have it. Two protocols using DAGs in very different ways, but mostly replacing the Blockchain structure.

Kaspa and Hedera are not alone though. Some other protocols like Taraxa or BlockDAG (which is interesting, because it’s like calling a Blockchain “Blockchain”) are also trying their hand at DAGs.

I honestly don’t know if this will be the future or not, but what I like is that the Blockchain space is totally filled with cool and innovative ideas, constantly pushing the boundaries of what’s possible.

And in my humble opinion, that’s what makes it so appealing!

Having said that, the next destination in our journey will again take us back into familiar grounds, as we’ll be exploring another Blockchain. You know, no crazy underlying structures. However, this next Blockchain brings very cool ideas to the table, and is perhaps different from what we’ve seen so far.

I’m talking about a personal favorite: Polkadot. And we’ll start piecing it apart in the next article!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.