Blockchain 101: Beyond The Blockchain (Part 1)

This is part of a larger series of articles about Blockchain. If this is the first article you come across, I strongly recommend starting from the beginning of the series.

The common factor throughout our journey together has been the very same structure that gives the series its name: the Blockchain.

Apart from our brief look at Ripple, every single system we've analyzed so far centers around the idea of a Blockchain — the data structure — as a means to organize transactions into a unique shared history of events.

Often times, we've left the structure itself in the background pretty much untouched, and focused on other aspects like how consensus is achieved, or how to process transactions faster. In doing so, we've foregone analyzing if the Blockchain itself was a good architectural decision.

Briefly recapping what we talked about closer to the beginning of the series, we know that a Blockchain is this type of linked list where references to the previous element — or block — are stored as the hash of said element. In consequence, every single block is tied cryptographically to all its descendants, making the entire chain immutable.

Sounds good — and most of the ecosystem is indeed built around this data structure. But I want us to stop for a moment and ask ourselves: could we use another data structure?

Today, we’ll be tackling this question by looking at a system we’ve been working with for a couple years at SpaceDev, which proposes an entirely different model: Hedera.

Back to the Beginning

From the very beginning of the series, we've praised the Blockchain (the data structure) as a good way to organize a history of events. We saw some slight variance with Solana's Proof of History and its timestamping capabilities, but ultimately, everything is still placed on a Blockchain.

Our original requirement was simply to be able to order transactions. All we really need is to determine a correct order of execution. If we could find another way we could go about it in a decentralized way, we may have just encountered an alternative to Blockchains!

One such solution is the one implemented by Hedera. The structure and consensus they use is called the Hashgraph Consensus Mechanism, and I promise you — it's nothing like what we're used to.

The Hashgraph

So how does this work?

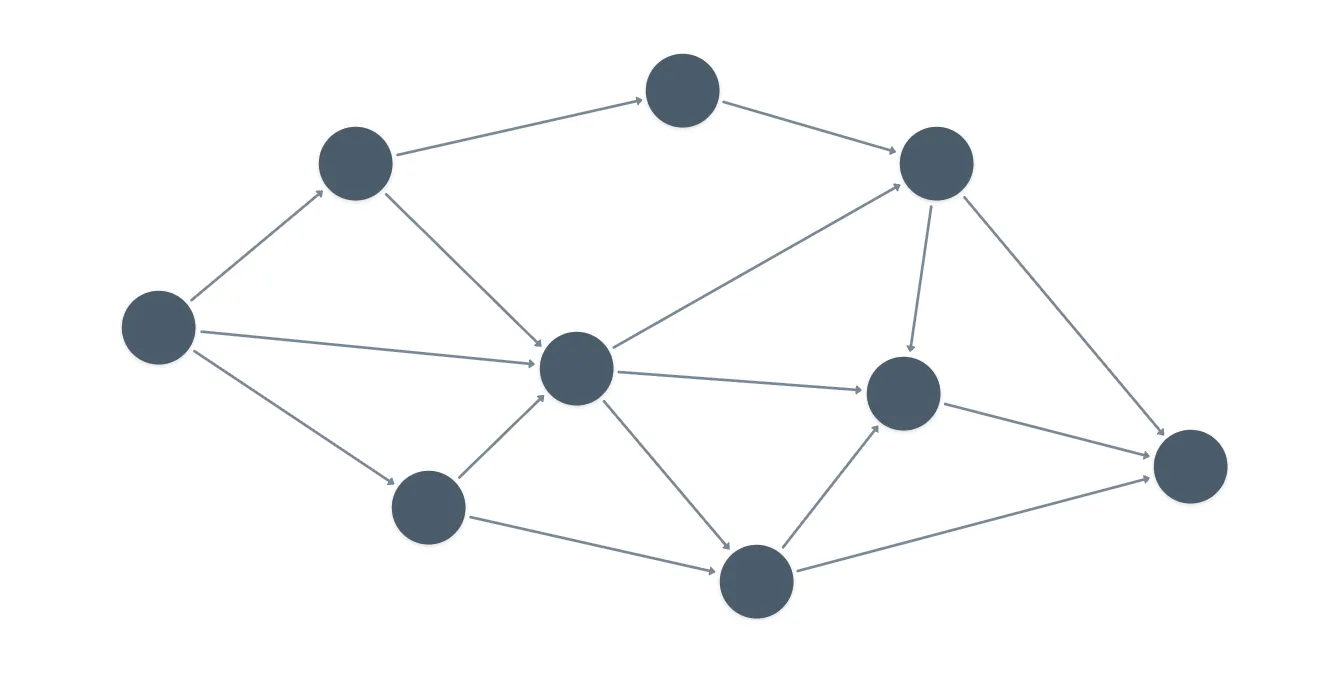

First, let's talk about what a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) is. As you might have guessed by the quite descriptive name, it's a graph with directed edges. And crucially, it doesn't have any cycles: if you start at any node and start following edges, you'll never return to the same starting node.

The Hashgraph is simply a DAG, where the edges are pointers to the hash of another node. Implicitly, we're saying that each node has some content, much like blocks in a Blockchain also have a content that can be hashed to produce a unique identifier.

It's important to get this out of the way early, because the entire consensus mechanism for Hedera is based on the properties of this data structure.

To motivate what follows (and hint at the usefulness of a DAG), let's get back to Proof of Work for a moment. When two miners create new blocks at the same time, the network has to choose one and discard the other. When we scale to more and more miners, this becomes extremely wasteful, as most blocks are discarded.

The key insight is that we could try to avoid throwing away all that valuable effort and perfectly valid information — and this is where the Hashgraph comes in: by allowing the incorporation of multiple data sources simultaneously.

Hashgraph Consensus

Alright, we've got the structure in place. What exactly do we use it for? And what are the nodes in the Hashgraph supposed to be anyway?

Everything starts with Hedera's gossip protocol. We've already talked about gossipping earlier in the series, and we should already be acquainted with the general idea: passing messages around between peers, so that they reach every member in the network eventually.

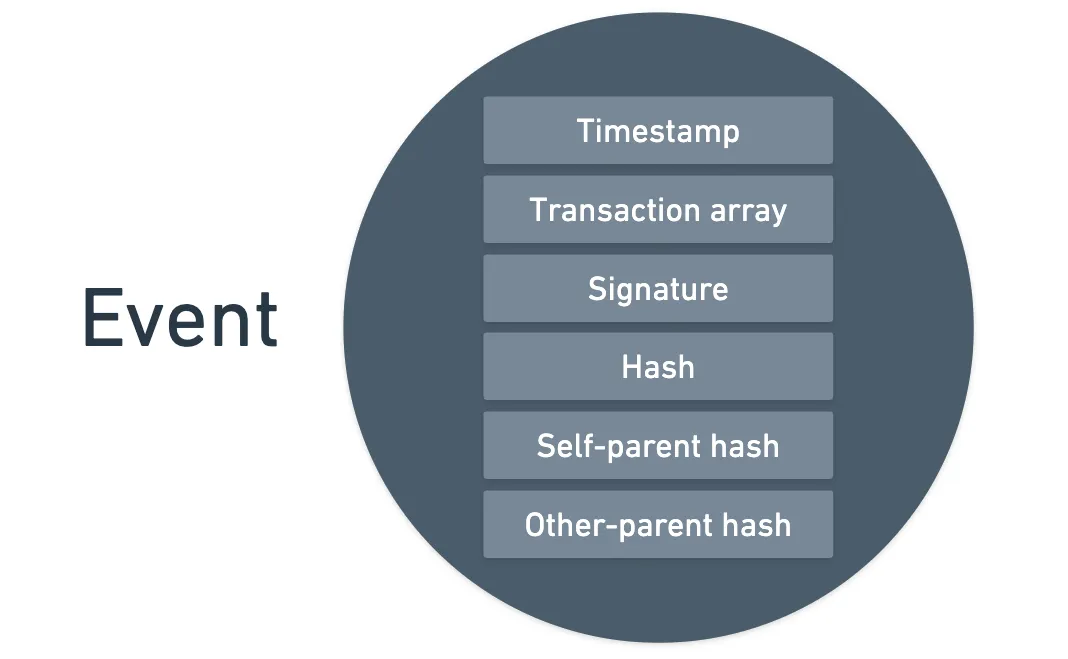

But Hedera's gossip protocol is built different. They communicate in events, which are simple data structures containing a few elements: a timestamp, an array of transactions, a signature (proving the sender's identity), and two hashes (pointing to other events), and of course, their own hash.

All those elements are key for the overall process to succeed — but before specifying each of their roles, I want to first place our focus on that pair of hashes in the event.

Events are exchanged between nodes at random as the result of syncing about the observed state of the network.

Don't worry, it will make sense soon.

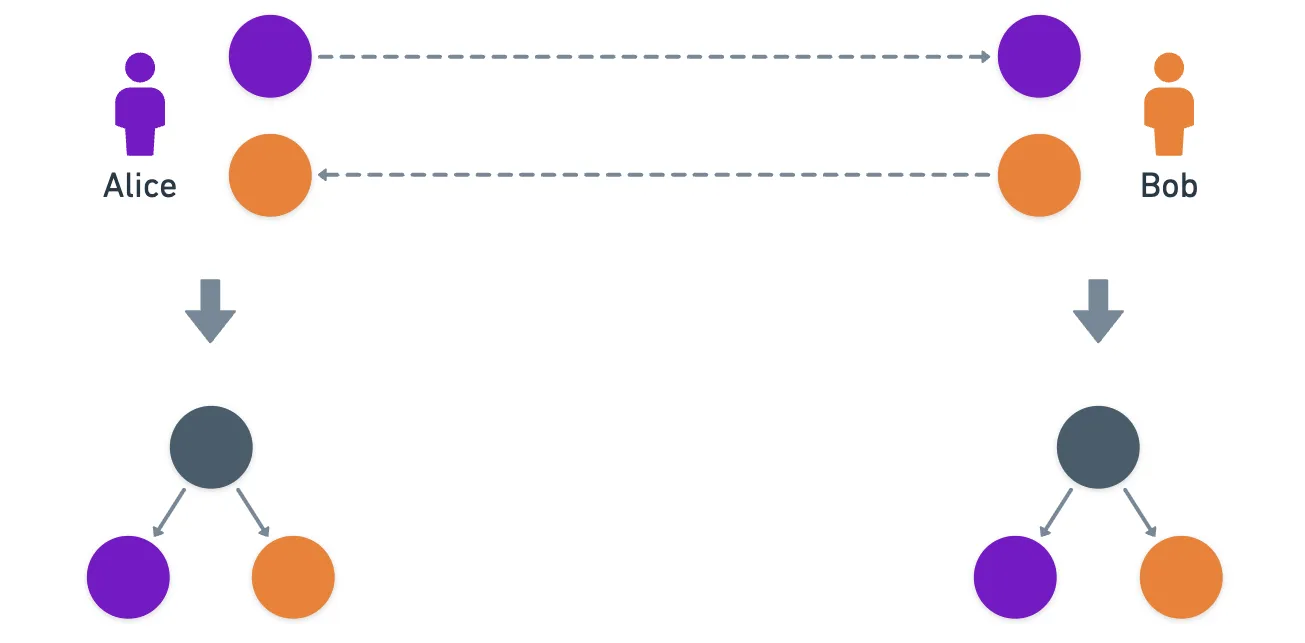

So let's imagine Alice and Bob are about to sync. They exchange their latest observed events, meaning that they now possess two events each: their very own latest observed event, and the other party's latest observed event. These are the self-parent event, and the other-parent event respectively.

And it's in the next step that things start coming together, literally: both Alice and Bob create a new event pointing to the two old events, through their hashes. This will become their new latest observed event, so in the next communication with another node, they will sync using this fresh event.

Notice that after the sync, both Alice and Bob will have created separate events that are mirror images of each other — their only difference being the order of the self-parent hash and the other-parent hash. In essence though, they carry the same information.

As an important side note: the array of transactions in the new event is either empty, or includes new transactions that each node wants to include into the network. The old transactions are not copied over to the new event.This is also one of sources of differences between these two sibling events!

During the sync, the participants also exchange all their event history — or at least, all the events the other node has not seen yet. So now, they both have almost the same history of events — the same Hashgraph.

This has an important consequence: Alice can know about Charlie's past events without ever syncing with him, as long as he has synced with Bob previously.

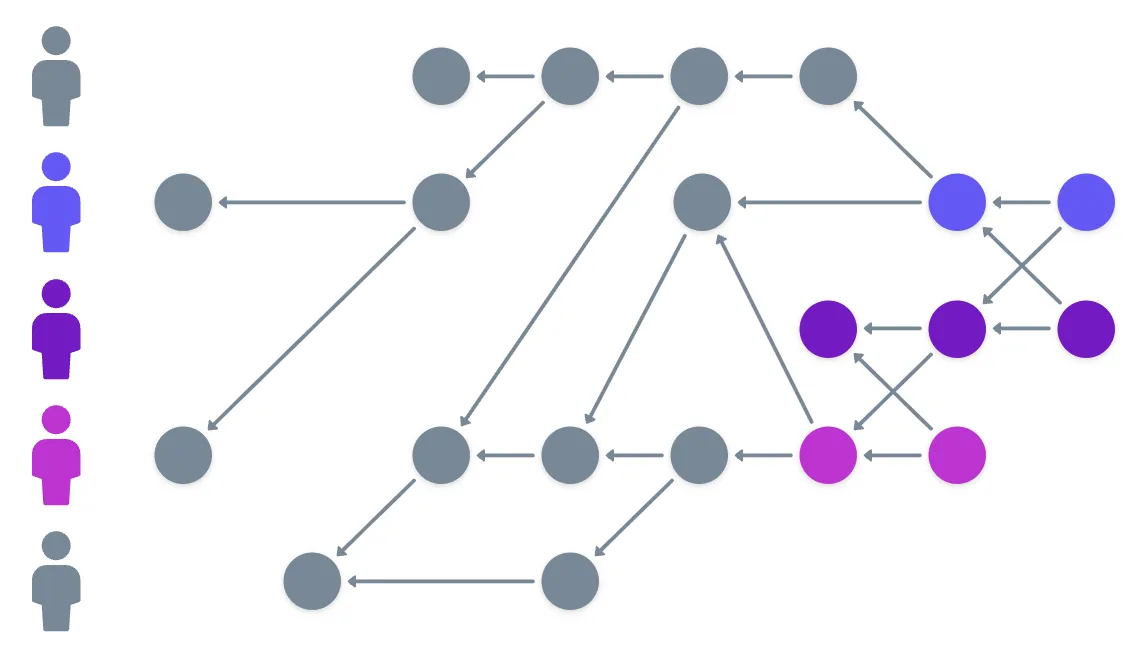

As you can see in the diagram above, after syncing with only two nodes, we get information of events produced by other nodes, because of previous syncs between peers. Kinda cool!

By adding more players to this game of sync (through random pairings), what happens is that over time, every peer in the network will eventually have the same Hashgraph. And that will form the basis for consensus!

Transaction Timestamps

Let's not lose sight of our goal here, though: we need to put timestamps on transactions, so that we can properly order them.

As network participants, we have this ever-growing graph at our disposal — so how about we try to derive a timestamp from it?

The Hashgraph contains a wealth of information. Importantly, each event has a timestamp, but the thing is it could be wrong or malicious. However, with enough information the network can collectively and fairly decide when each transaction occurred, through a process called virtual voting.

Virtual Voting

Normally, voting involves exchanging messages with votes between peers. This translates into latency, and an overall slower consensus mechanism.

But by analyzing the Hashgraph structure, Hedera does something brilliant: each node can deterministically determine how every other node would vote on when each transaction occurred, without explicitly exchanging any votes.

Yeah, it's quite the fancy mechanism. Let's try to take it slow. Please bear with me for a second.

And there's also the explanation by the Hedera team. You might want to check that out as well!

The algorithm is all about visibility. It relies on the idea of witness events, which we can think of as checkpoints. And the process is divided into three steps:

- Round division (and witness creation)

- Fame determination

- Ordering

We'll tackle one at a time.

Round Division

When a node publishes its very first event, we consider it to be its very first witness event, indicating the start of round . Rounds will serve as a measure to divide time into discrete chunks, and help with the timestamping process.

Witness events are simply the first event created by a node in each round. We'll see how we determine this in just a moment.

Then, the node will start participating in gossiping, learning about more and more events. Eventually, it will have visibility (by traversing the Hashgraph) of the witness events of other nodes for the current round, .

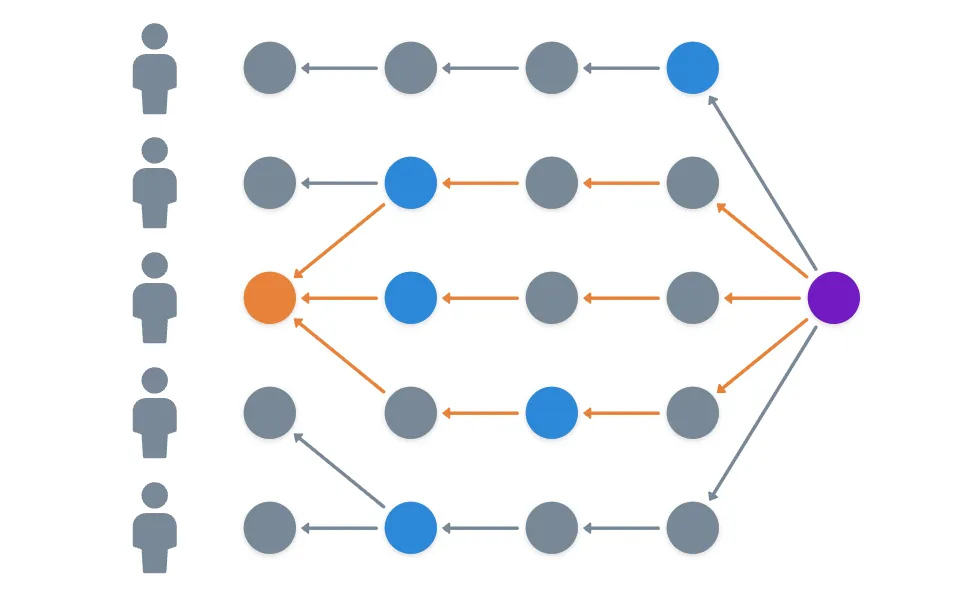

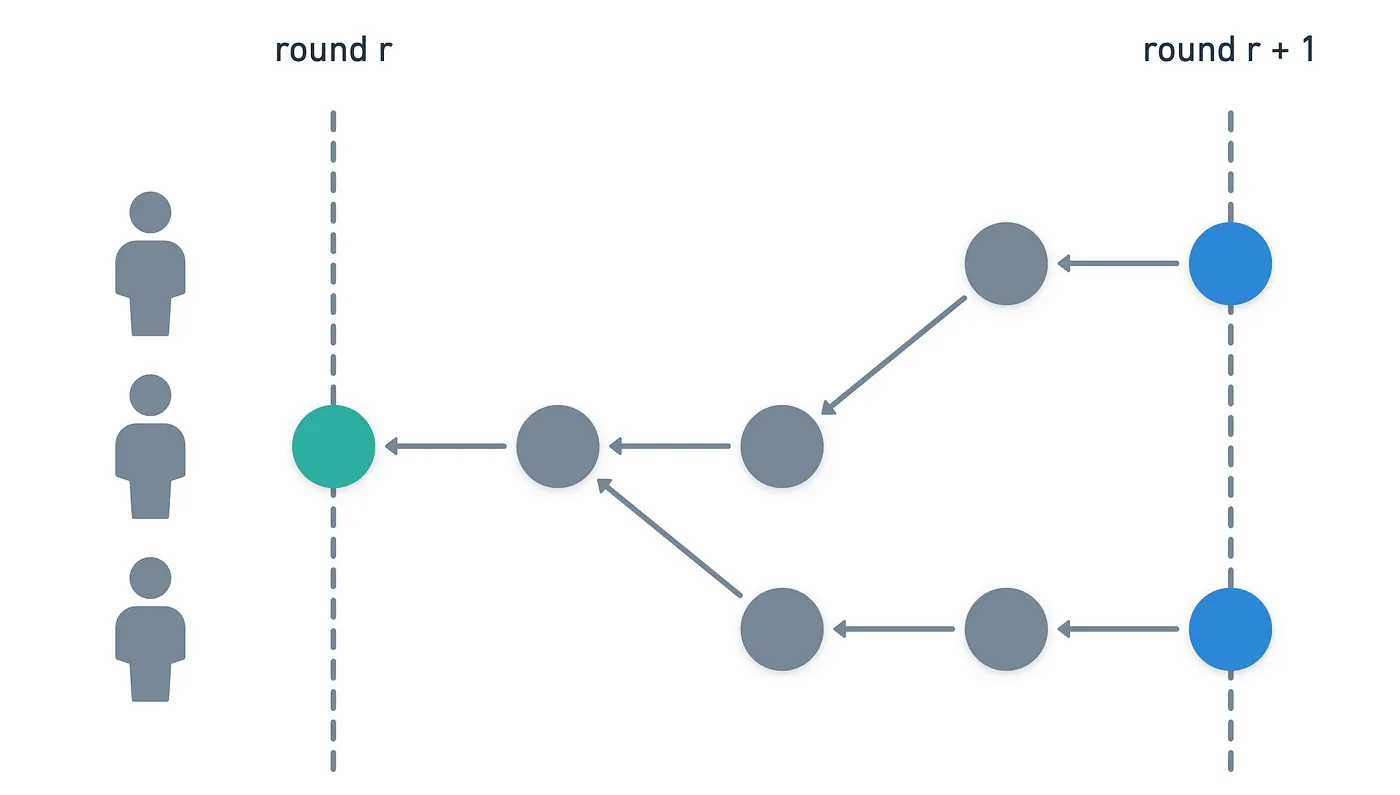

And here, we must make a distinction. Seeing an event means that there's some path from an event to an event in some current version of the Hashgraph held by a node. But strongly seeing means that we can find independent paths from to that pass through witness events of more than 2/3 (a supermajority) of the network participants.

Yeah, read that again. It takes a moment to wrap your head around it.

Something like this:

In the image, the purple event strongly sees the orange event, as we can find independent paths that go through the witness events (in blue) of 3 out of 5 participants.

When a node creates an event that can strongly see witness events for round for more than 2/3 of the network participants, then that event becomes a witness event for round , marking the start of a new round for that node.

The idea behind this is that nodes confirm the previous round is well-established before moving forward. And they can do this when they have sufficient knowledge and observability of the network state.

Since it's a bit complicated, let's try to put this in practice by examining a simple example, in the shape of a toy three-participant network. That's enough to understand a few caveats here and there.

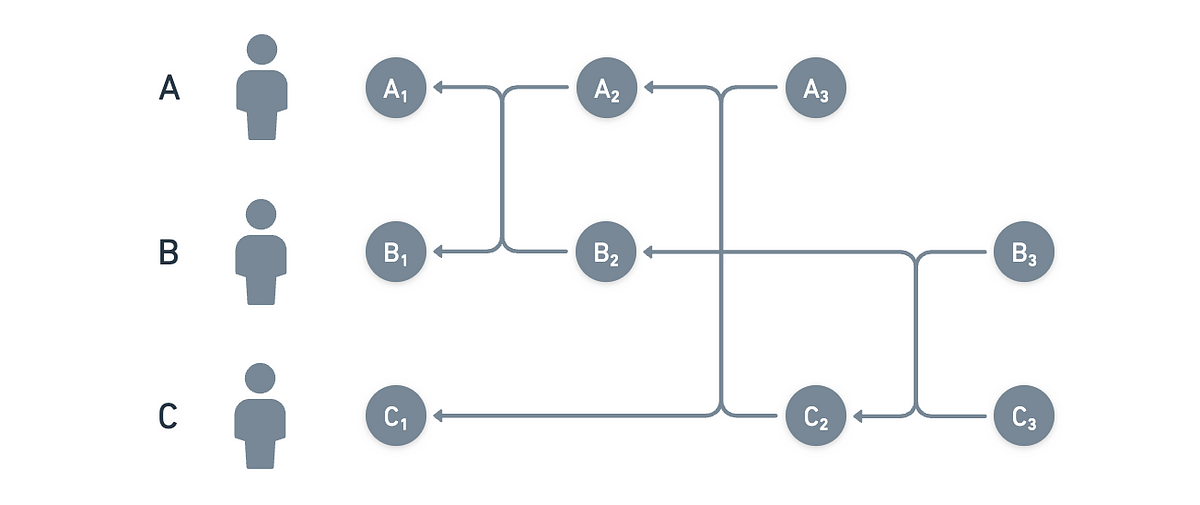

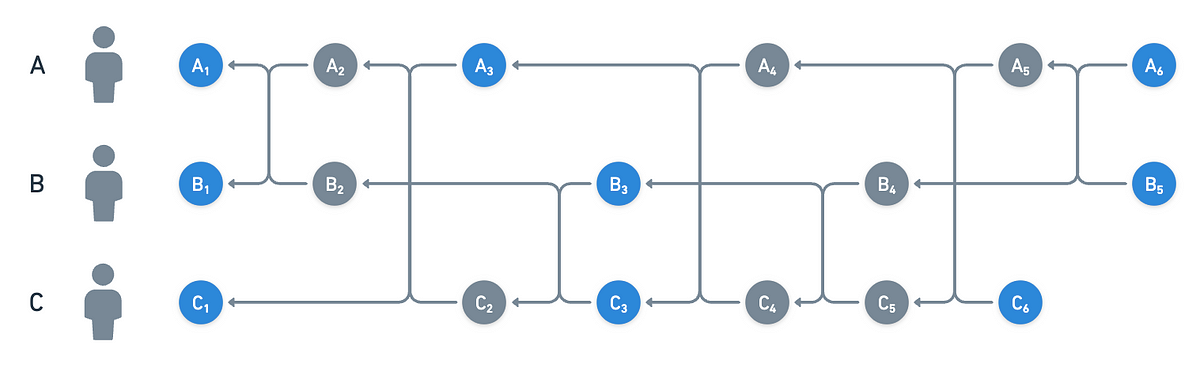

Let's suppose we have three nodes , , and , and each of them creates their very first event. Let's label those , , and , since all of them are round witnesses. Next, let's follow a few sync cycles:

- Sync 1: A + B: creates (pointing to and ), and creates (pointing to and )

- Sync 2: A + C: creates (pointing to and ), and creates (pointing to and )

- Sync 3: B + C: creates (pointing to and ), and creates (pointing to and )

All that looks like this:

Now we need to unpack, and see if we can determine who the witness events for round are.

Remember, the condition to advance to the next round is that witness events are strongly seen.

From the perspective of , we have that is the first event that can see more than 2/3 of the witness events from the previous round. But we need strongly seeing, not just seeing!

Which means there's a problem - and this calls for a special case: all events from round are considered to be strongly seen. This is an important bootstrapping condition - without it, the network would not be able to come to consensus at all.

With this consideration in mind, is the witness event for round for . Likewise, and become witnesses for round for and respectively.

Once we have two rounds, we can continue the process and successfully advance the network. Following the same logic, this is how the Hashgraph would look like after a few more syncs, with witness events marked in blue:

I should note that witness events don't have any special markers on them — anyone can determine whether an event is a witness purely from the structure of the Hashgraph. And they do mark them, but locally.

Witness events, check. Now, how do we use them?

Determining Fame

Now we get to the heart of virtual voting: determining which witness events are famous.

Jokes aside, fame is a mechanism to filter out witnesses. In short, not every witness becomes famous, and only famous witnesses become legitimate checkpoints for the network — and are taken into account for consensus decisions.

That's the theory, at least. But how do we determine fame, and what happens once we do?

To determine the fame of a witness, we look at the Hashgraph, pick a witness for round (let's call it ), and ask ourselves the following question: does the witness for round of node see ?

Notice that we require simple seeing here — any path between the two witnesses will do!

Conceptually, what we're asking is if some node knows a witness, and if it does, it counts as a vote for its fame.

When a witness gathers a supermajority of votes (more than 2/3), then it becomes famous. And again, this is akin to saying:

The majority of the network knows this witness

Great! We're almost there.

Transaction Ordering

So we've divided time into rounds, identified witness events, and determined which ones are famous. Now comes the final step: using these famous witnesses to determine exactly when each transaction occurred.

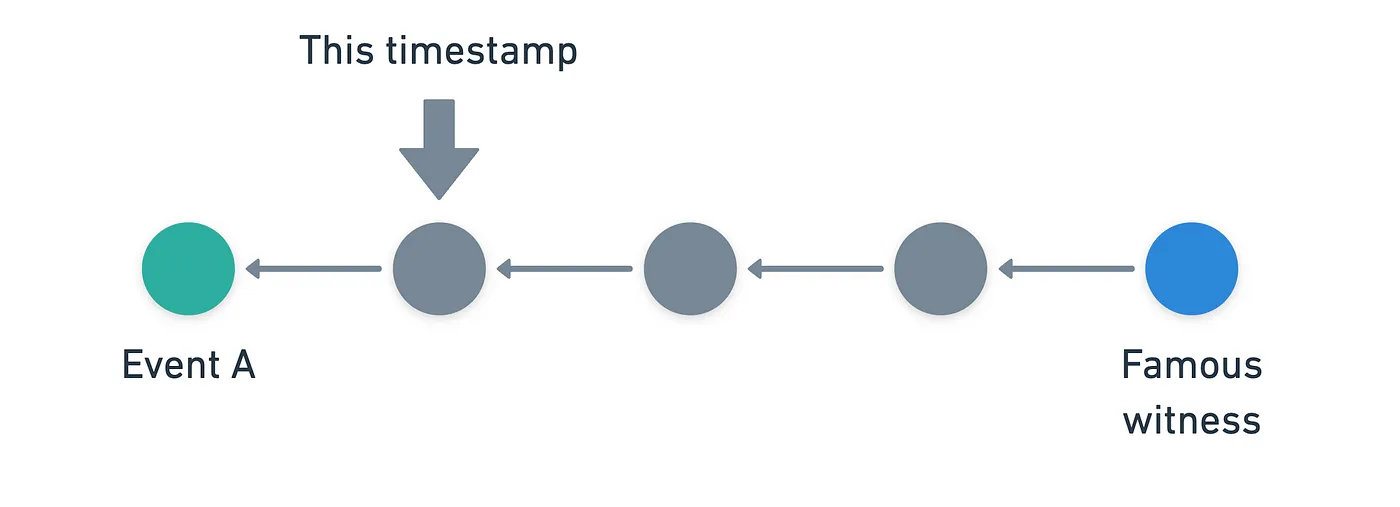

Remember: our goal is to determine a timestamp for an event — and also the transactions contained in it.

Let's say we want to timestamp event . In reality, this event (and all events) will have their own timestamp — but as previously mentioned, the problem is we cannot know whether this timestamp isn't clock-drifted, or even if it is malicious. We just can't trust it. So we'll need a different approach.

We define the moment when a witness first learned of some event as the timestamp of the immediate descendant of , that is also an ancestor of the witness. I think an image will help:

Having defined this, then the process is very straightforward, and it has only two steps:

- The algorithm starts by determining the round where all famous witnesses can see our event . This is important — we need full visibility from the judging panel (aka the set of famous witnesses) before we can make a timestamp decision.

- Then, we simply takes the median of the moments when famous witnesses first learned about event .

And that's it! It's as if each famous witness votes with a timestamp, and then, to be completely fair, we simply assign the same weight to each vote.

Finally, once an event is timestamped, then the transactions contained in that event will be assigned the same consensus timestamp. And if multiple transactions share the same timestamp (which can happen), then they're ordered by some additional criteria like signatures.

Most likely lexicographically, which means alphabetically but in binary or hexadecimal. I didn't find the exact method though.

This achieves our final goal: obtaining a total ordering of all transactions across the entire network! And what's truly remarkable is that every node will arrive at the same ordering, without ever exchanging any votes.

A Couple Notes

If you've been following closely, you might have a lingering question. You see, we established we need a supermajority (more than 2/3) of voters to determine the timestamp of an event. But how can we be sure that two nodes don't have** different supermajor sets**?

And you'd be absolutely right to ask! It's one of the most subtle aspects of the Hashgraph consensus mechanism.

When combining the three mechanisms above, we can use some results from set theory to prove there's sufficient overlap to ensure everyone will reach the same conclusion. Yes, nodes will have temporary different views of the Hashgraph, but the magic lies in only timestamping events that are "deep enough" into the DAG.

But this only works if 2/3 of the nodes are honest. Every single distributed system has this kind of threshold for correct operation — or in more technical words, the threshold that guarantees Byzantine Fault Tolerance. Hedera happens to have a relatively high threshold, so it is a fundamental requirement that nodes are very trustworthy.

For this reason, Hedera operates as a consortium model rather than being fully permissionless. The network is governed by a council of established organizations — companies like Google, IBM, and others — who run the consensus nodes. Unlike Bitcoin, where anyone can join as a miner, Hedera carefully picks and chooses its consensus participants to ensure the 2/3 honest assumption holds in practice.

As always, it's a trade-off: you get incredible speed and finality, but you sacrifice some decentralization for reliability.

Another aspect to consider is that unlike a Blockchain, this Hashgraph structure can't grow indefinitely — it would simply consume too much memory. Because of this restriction, once events are old enough and their consensus has been finalized, nodes prune away the old portions of the Hashgraph.

What remains is the ordered transaction history — the final state that results from applying transactions in their consensus order. The Hashgraph itself is just a temporary machinery used for consensus, but needs to be kept in check in terms of size.

As promising as this sounds, it's worth noting that there's another important trade-off: while the Hashgraph achieves fast consensus and high throughput, it sacrifices the Blockchain's full immutability guarantees. In other words, a Blockchain allows you to trace back all transactions up to the very genesis block, and verify the entire history if needed. With Hedera's approach, you're trusting that the pruned consensus was computed and stored correctly.

Bet you didn't see that one coming!

So again, nothing's for free. I feel like I've repeated this a lot lately, but it's a fact that simply cannot be understated!

Summary

We've discussed something super valuable today: the Blockchain itself is not the only available solution to distributed ledger technologies, or distributed consensus. And for all we know, it might not even be the best one.

I mean, we're not even 20 years into the history of Blockchain yet! Who knows...

Hedera's approach is certainly a very different one, as we don't have miners or validators — just nodes collaborating through gossiping. And the Hashgraph structure simply captures the full communication history of the network, and doesn't discard anything.

The breakthrough lies in the virtual voting mechanism. It can be a bit hard to wrap your head around, so I recommend giving it a couple reads if needed.

Admittedly, I had to read it a couple times while writing this article!

If anything, Hedera's solution shows that sometimes the most elegant solutions emerge from questioning our fundamental assumptions, or at least the assumptions of the technology. In the end, the message is to keep our minds open to new ideas and possibilities!

And just to clarify, I'm not trying to sell Hedera here, as I haven't really done with any other Blockchains in the series. Remember that it comes coupled with some trade-offs as well, and it's ultimately up to us, the users and developers, to choose the network that better suits our needs.

Okay! That's enough preaching for a single article.

In the next one, I want to keep exploring these departures from the standard model, but let's try to keep it more familiar. We'll look at a reversion of an old friend, Proof of Work, and what we can do to avoid wasting computational work.

Until then, my friends!

Did you find this content useful?

Support Frank Mangone by sending a coffee. All proceeds go directly to the author.